Early release of Bilkis Bano gangrape convicts | Judgement Summary

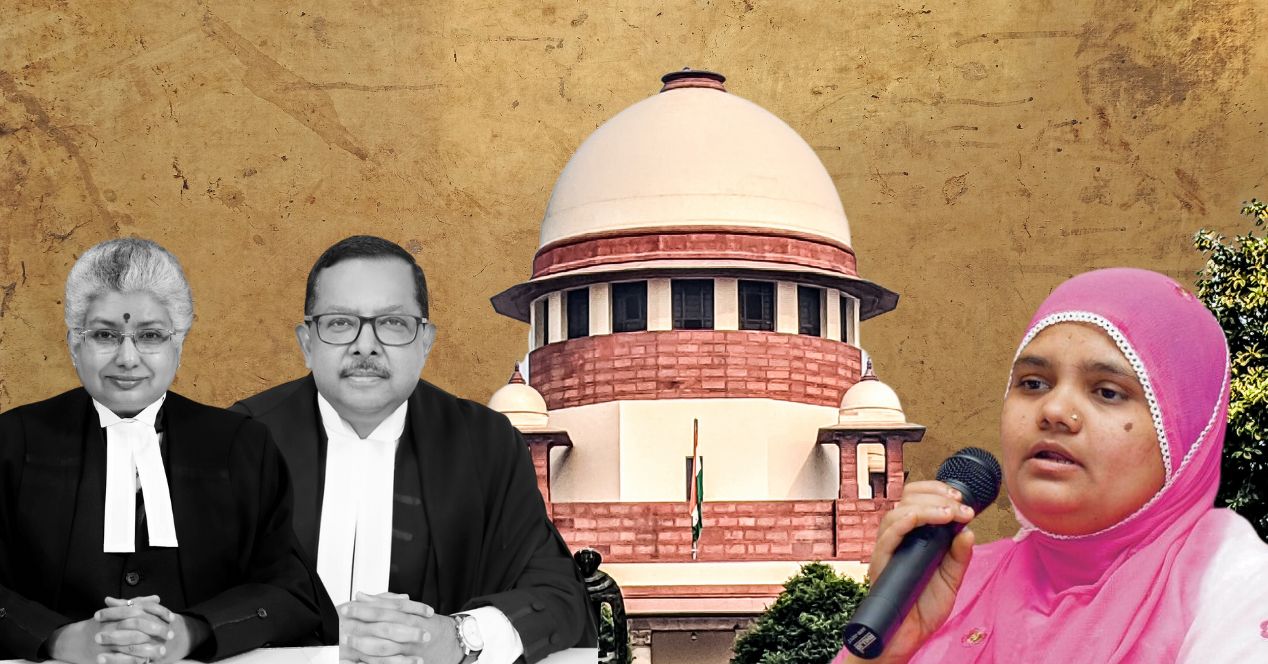

Early Release of Bilkis Bano Gangrape ConvictsJudges: B.V. Nagarathna J, Ujjal Bhuyan J

On 8 January 2024, a two-judge Bench of the Supreme Court set aside remission orders granting premature release to 11 convicts in the Bilkis Bano gangrape case. The 251-page judgement was authored by Justice B.V. Nagarathna where she directed the 11 convicts to return to prison within two weeks.

The judgement centred around issues of maintainability of petitions, the authority of the Gujarat government to grant remission, and the personal liberty of the convicts. The judgement favoured the petitioners in all of these aspects.

Bilkis Bano “rightly approached” the Supreme Court under Article 32

The Judgement upheld the maintainability of Bano’s petition. It stated that Article 32 is the “soul of the Constitution” used for the enforcement of fundamental rights. Bano approached the top court for the enforcement of fundamental rights under Articles 14 (right to equality) and 21 (right to life and personal liberty).

Senior Advocate S. Guru Krishna Kumar had argued that Bano should have approached the Gujarat High Court under Article 226. This keeps the remedy of appeal in the Supreme Court as a second option. Justice Nagarathna wrote that Bano’s petition could not be dismissed on the grounds of an alternative remedy.

Justice Nagarathna pointed out “another stronger reason” for upholding the maintainability of the petition. Radhe Shyam, one of the convicts, had approached the Supreme Court under Article 32 praying for the Gujarat government to consider his remission. On 13 May 2022, the Supreme Court directed the Gujarat government to consider remission under the 1992 Gujarat Policy.

Relying on the above facts, the judgement stated that the Gujarat High Court would not have been in the position to entertain the petition in light of the Supreme Court direction issued in May 2022. This justifies Bano’s petition as it also dealt with the question of “appropriate government.”

Maintainability of PILs challenging remission unanswered

The judgement kept the question of maintainability of Public Interest Litigations (PILs) open.

After the convicts were granted remission, several members of civil society filed PILs challenging the release. The Gujarat government and the convicts challenged these PILs contending that the petitioners cannot involve themselves in a criminal trial. The petitioners had justified these PILs by arguing that remission orders can affect society at large. Additionally, the merits of remission was a part of the administrative domain and not a criminal case. Without missing a beat, they also pointed out that the heinous nature of the offences in question warranted these PILs.

The judgement held that the merits of the remission orders were considered under the petition by Bano. It stated that the maintainability of PILs was an “academic” discussion which need not be answered in the present case.

Maharashtra government competent to consider remission of convicts

The judgement held that the “appropriate government” under Section 432(7) of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 would be the place of trial and sentence of the offender. It would not be the place where the trial was conducted, as submitted by the Gujarat government. Further, the opinion of the presiding judge of the convicting court plays a critical role when a convict makes an application for remission. In the present instance, the convicting court and its presiding judge were both in Maharashtra.

Bano’s trial was transferred to a special court in Maharashtra owing to concerns of fairness and witness protection. Noting these details, the judgement held that the place of crime and imprisonment cannot be a consideration. Additionally, it held that the definition of “appropriate government” also covers instances “wherein the trial is transferred by this Court…in the interest of justice from one State to another State.”

Reliance was placed on State of Madhya Pradesh v Ratan Singh (1976) where the Supreme Court held that the convicting state of Madhya Pradesh would be the “appropriate government” even if the convict was discharging his sentence in Punjab. It also relied on Union of India v V. Sriharan (2016) where a Constitution Bench reinforced the above definition of “appropriate government.”

Justice Nagarathna wrote that the Gujarat government should have dismissed the remission application on these grounds alone.

Convicts played a “fraud” on the Supreme Court

The judgement declared that the May 2022 Order of the Supreme Court directing the Gujarat government to consider remission was per incuriam i.e. not based on law or fact. The Order did not consider V. Sriharan.

Justice Nagarathna reasoned that Radheshyam, the convict behind the May 2022 petition, suppressed critical facts when he approached the Supreme Court. He had also approached the Maharashtra government to consider his remission application after the Gujarat High Court dismissed his petition. In Maharashtra, his application met with negative recommendations by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the Special Judge (CBI), Mumbai from the convicting court. Further, the Superintendent of Police and the District Magistrate of Dahod recommended against his release.

Radheshyam had contended that there was a “diametrically opposite” view of the Gujarat High Court and the Bombay High Court on his remission petition. The judgement also pointed out that Radheshyam suppressed key facts regarding the nature of the two petitions. The opposite view held by the Bombay High Court was in a petition where the question of remission was not even an issue. It dealt with the transfer of the convicts from Maharashtra to a prison in their home state of Gujarat. Justice Nagarathna noted that Radheshyam had suppressed the backgrounds of these petitions as well.

Lastly, the judgement held that the proceedings for remission started only through Radheshyam. This means that there was no direction to consider the remission of any other convicts.

As the May 2022 Order was declared a nullity, all subsequent developments would also be withdrawn. This means that the Gujarat government’s order of remission—a direct result of the May 2022 order—stood quashed.

Gujarat government was “complicit” in the fraud

“The State of Gujarat has acted in tandem and was complicit,” stated the judgement. In Radheshyam’s petition, the Gujarat government had taken a different stance. It argued that the Maharashtra government was the “appropriate government” to consider remission. Justice Nagarathna wrote that the “appropriate government” should exercise the power to grant remission “in accordance with the law” and not in an “arbitrary or perverse manner without regard to the actual facts.”

The judgement claimed that the Gujarat government did not file a review petition to correct the May 2022 order of the Supreme Court. It claimed that “ensuing litigation would not have arisen at all” if the Gujarat government had informed the Supreme Court of this error. Further, as no such review petition was filed, the Gujarat government usurped the power of the Maharashtra government. Subsequently, other convicts who were not involved in the petitions also filed remission applications relying on the May 2022 Order.

No liberty at the cost of rule of law

Until the remission orders were set aside, they bore the stamp of validity resulting in more than a year-and-a-half of freedom for the convicts. A question faced by the Supreme Court was whether the personal liberty of the convicts under Article 21 should be protected i.e. should they be allowed to continue their freedom?

One of Bano’s arguments was that the convicts should be sent back to prison because the rule of law had been complied with. The judgement accepted the argument, holding the liberty of a person can only be protected in accordance of the law. It stated that liberty and other fundamental rights will only prevail if rule of law is established. Further, it iterated the role of the Supreme Court in acting as “a beacon in upholding rule of law.”

Adopting this reasoning, the judgement held that the convicts cannot be allowed to stay out of jail as it would be a violation of the rule of law. It also pointed out that “emotional appeals” about liberty and reformation “become hollow and without substance” when juxtaposed with the abuse of process.

The convicts were directed to report back to the jail authorities within two weeks of the judgement.