Analysis

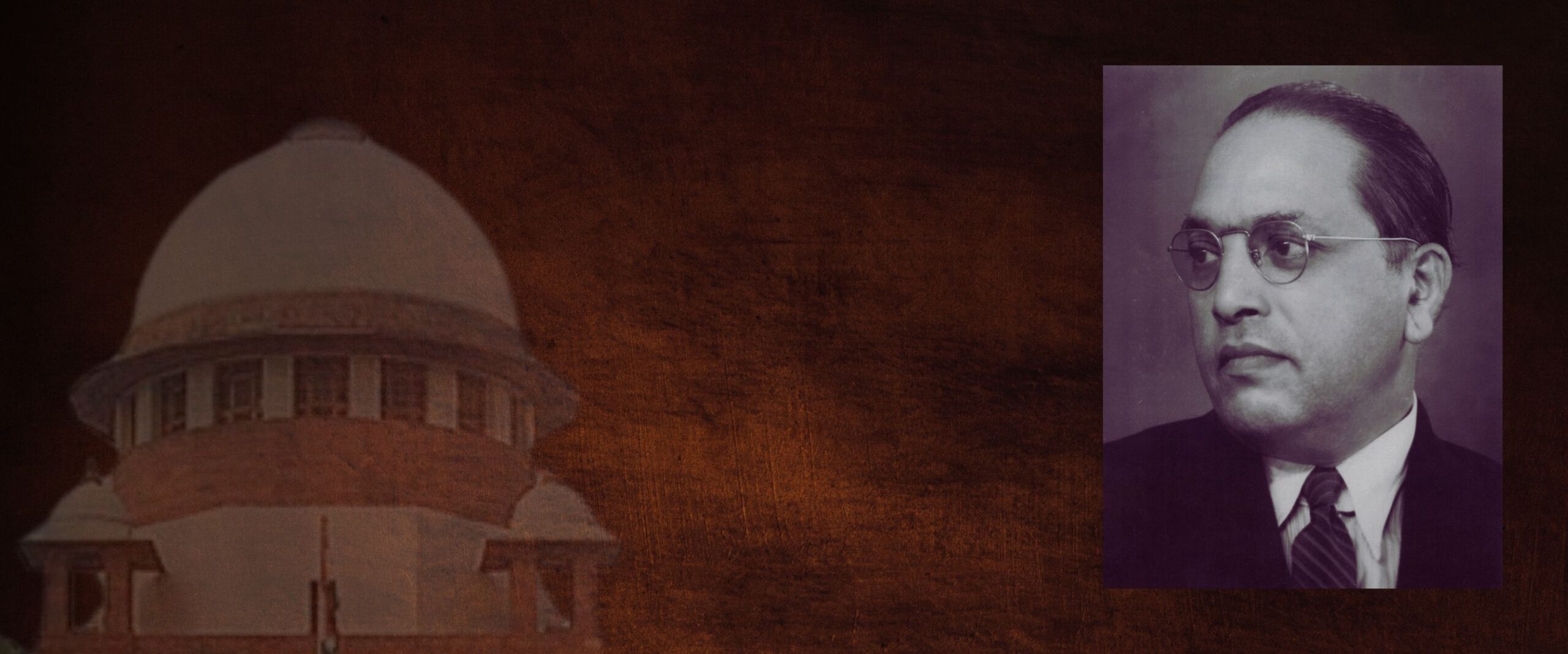

When Dr Ambedkar argued in the Supreme Court

In his only known case in the SC, the key architect of the Constitution evoked its ‘spirit’ in a precursor to the Basic Structure doctrine

It’s the weekend of Dr B.R. Ambedkar’s 133rd birth anniversary so we peeked into the one matter he is recorded as having argued in the Supreme Court.

The year was 1952. Ambedkar had resigned as law minister only recently. One of the hottest topics of the day was land reform, which had led to some of the Supreme Court’s earliest decisions on fundamental rights. In State of Bihar v. Kameshwar Singh, Ambedkar was arguing for a batch of zamindars from Uttar Pradesh.

It comes across as an anomalous choice of client, given his steady record of opposing dominant caste interests in his Bombay High Court practice. The historian Rohit De has suggested that Ambedkar partly took up the case because it was lucrative.

In a previous case, the Supreme Court had upheld the First Amendment, which protected legislation related to land reform from judicial review. In Kameshwar, Ambedkar and his fellow counsel had to think up a new route to challenge the takeover of their clients’ land. Ambedkar argued that the compulsory acquisition of property without public necessity and without just compensation went against the “spirit of the Constitution.”

Here’s how the judgement summarised Ambedkar’s contention: “The Constitution, being avowedly one for establishing liberty, justice and equality and a government of a free people with only limited powers, must be held to contain an implied prohibition against taking private property without just compensation and in the absence of a public purpose.”

This contention was not accepted in Court but De has argued that it sowed the seeds for the acknowledgement of the Basic Structure doctrine in Kesavananda Bharati in 1974. The idea of the ‘spirit’ then informed judgements that went against the executive during the Emergency and deepened the ‘due process’ protection against Article 21 violations.

It’s thrilling to contemplate that the key architect of the Constitution was probably one of the first to bring up its ‘spirit’ in front of the institution tasked with being the document’s final interpreter. It was an early acknowledgment that, despite the Indian Constitution’s prodigious length, meaning would have to be poured into it from time to time.

It is not a uniquely Indian evolution. In the US, for instance, the text of the Constitution has become quieter and more terse over time. Its predecessor, the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780, was a verbose document, with articles detailing the “origins and purpose of society and government” and the “character” of elections and institutions. In contrast, lawyer Christopher C. Demuth calls the present US Constitution a “matter of fact account” that is “strictly business.” In 1819, Chief Justice Marshall, in McCulloch v. Maryland, suggested it was on the judiciary to fill those silences. What was being tested should be “consistent with the letter and spirit of the Constitution,” he said.

Academic David Schwartz has written that the US Constitution’s ‘spirit’ has constantly changed over 200 years since McCulloch. This fluidity is what drives the project of transformative constitutionalism. It’s also what makes the project vulnerable. If our Constitution is silent, for example, about investigating agencies beyond acknowledging their existence, who controls how those silences are filled?

The ‘spirit’ has always been political. These days, it’s relied on to argue both in favour of and against a new Constitution. Mapping the glimpse offered by Kameshwar to the Ambedkarite movement conveys the sense that the ‘constitutional spirit’ may not have been an abstraction of high legal thought. In images, rallies and oral cultures passed down in blue, the spirit is reflected in anything that creates justice for the people.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!