Court Data

What types of judgments is the SC translating?

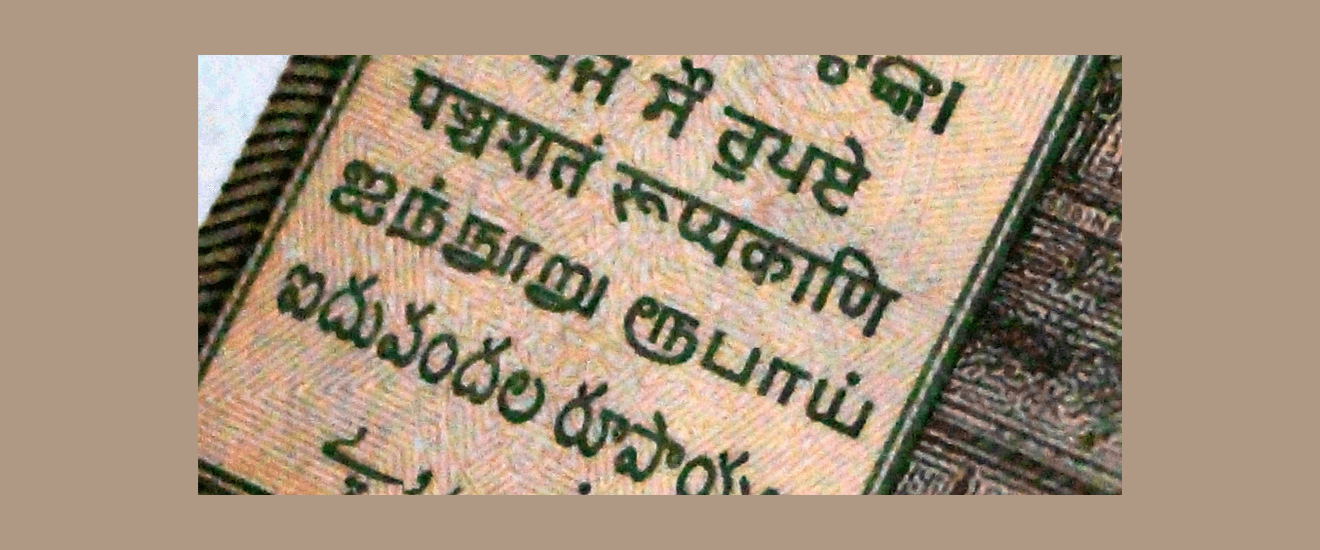

According to the SC Registrar, the AI software will translate judgments and orders into 9 vernacular languages.

Earlier this week, Bhadra Sinha reported that the Supreme Court is close to start using its artificial intelligence (AI) software to translate judgments. According to the Registrar, the AI software will translate judgments and orders into 9 vernacular languages. Justice L.N. Rao’s committee is overseeing the project.

As we previously explored, the Supreme Court has been using human translators to translate judgments into vernacular languages. While Article 348 of the Constitution states that Supreme Court judgments must be in English, the Court has recognized that this restricts its accessibility.

In its 2018-19 Annual Report (p.88), it declared its intention to make translations available in certain types of cases. It said, ‘the litigants in relation to these categories of cases, by and large, belong either to the lower or middle strata of the society and are considered to be not well-versed with English language’. It named the following 14 ‘subject categories’:

- Labour

- Rent Act matters

- Land Acquisition and Requisition

- Service

- Compensation

- Criminal Law

- Family Law

- Ordinary Civil Law

- Personal law

- Religious and Charitable Endowments

- Simple Money and Mortgage matters

- Eviction under the Public Premises (Eviction) Act

- Land Laws and Agricultural Tenancies

- Consumer Protection

Despite the AI software not being fully operational, the Supreme Court has been publishing translated judgments on its website. Has the Registrar followed through on the Court’s plan to publish judgments in the above categories? Or has it found that there is a need to focus on other subject areas?

Criminal judgments see most translations

After surveying a sample of translated judgments, we found that the Registrar is sticking to the plan set out in the 2018-19 Annual Report. As conveyed in the graph below, the Registrar translated judgments into all subject categories, except Rent Act and Religious/Charitable Endowments matters.

A large majority of cases fell into the Criminal subject category. Roughly 37% of translated judgments were Criminal matters. Among Civil matters, the largest number of translations were for Service related judgments. There were also a significant number of Ordinary Civil matter translations.

With the Court now introducing AI software, it will be interesting to see whether this distribution changes. And further, whether it matches up to the number of total judgments the Court delivers in each of these subject areas. We’ll have to wait and see.

Method of categorization: The subject category listed on Manupatra was used to determine subject category. In exception cases where no subject category was listed or multiple subject categories were listed, a subjective decision was made based on the facts of the case. Roughly 25% of cases were subjectively indexed.