Analysis

What is ‘temporal unreasonableness’ in constitutional law?

In a dissent in the Assam citizenship case, Justice Pardiwala proposed it as a ‘third prong’ to test the arbitrariness of a law. We explain.

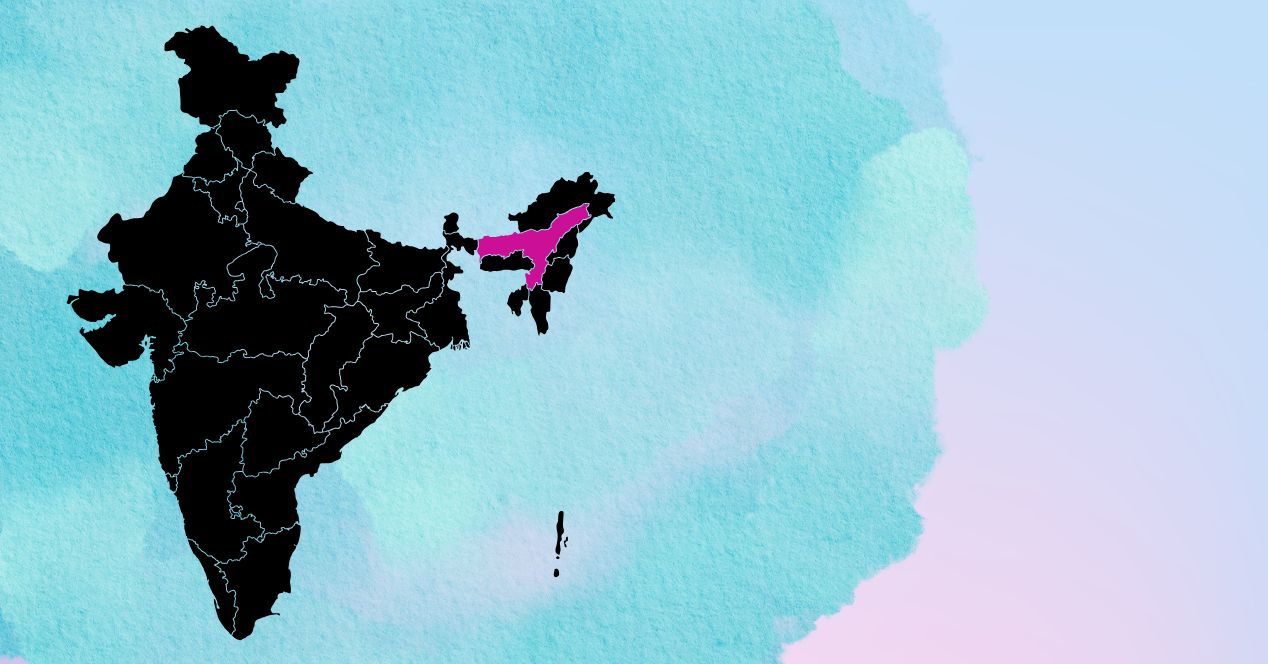

On 17 October 2024, a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955 in a 4:1 majority. The provision was inserted in 1985 to implement the Assam Accord, an agreement between the Union government and protesting groups who were demanding the deportation of illegal migrants. Section 6A grants citizenship to any person who entered Assam from Bangladesh before 25 March 1971.

Justice Surya Kant authored the majority opinion. Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud wrote a concurring opinion. Justice J.B. Pardiwala’s sole dissenting opinion stands out for stating that Section 6A should be struck down as it had lost its original object over time. He relied on the principle of “temporal unreasonableness”, observing that the provision counteracts its intended purpose and causes more harm than good.

How did Justice Pardiwala reach this conclusion? What is temporal unreasonableness?

What once was constitutional may not be anymore

A day after the verdict, Senior Advocate Shadan Farasat wrote that this was the first time in the “recent past” where the principle of temporal unreasonableness was used to strike down a provision, albeit in a dissenting opinion.

The principle suggests that a provision or statute can become unreasonable due to the passage of time, even if it was constitutional and valid when enacted. To declare a provision unconstitutional due to temporal unreasonableness, it is necessary to determine if it has become “manifestly arbitrary” with the passage of time. This principle has been evoked in several Supreme Court precedents. One of the most well-known is Joseph Shine v Union of India (2018), where temporal unreasonableness was relied on to decriminalise adultery.

In declaring Section 6A of the Citizenship Act unconstitutional, Justice Pardiwala cited a portion from Justice R.F. Nariman’s concurring opinion in Joseph Shine:

“This archaic law has long outlived its purpose and does not square with today’s constitutional morality, in that the very object with which it was made has since become manifestly arbitrary…On this basis alone, the law deserves to be struck down, for with the passage of time, Article 14 springs into action and interdicts such law as being manifestly arbitrary.”

While Justice Nariman didn’t didn’t expressly namecheck the principle of temporal unreasonableness in his Joseph Shine opinion, that is what he was effectively applying, as evidenced by his use of his phrase “with the passage of time”.

This excerpt from Joseph Shine outlines the test for manifest arbitrariness in the context of temporal unreasonableness. We will explore that test in the next section.

Applying temporal unreasonableness as a third prong

To determine whether a provision is manifestly arbitrary, its underlying logic must be tested for reasonableness. If the logic is irrational, the provision is manifestly arbitrary. This idea stems from the Latin maxim Cessante ratione legis cessat ipsa lex, meaning logic is the soul of the law.

If the reason for the law ceases, the law itself ceases. However, even if a rationale exists, it must align with constitutional morality or public interest to pass the test of manifest arbitrariness, as observed by Justice Surya Kant in his majority opinion.

The test for manifest arbitrariness requires two elements: reasonable classification based on intelligible differentia and a reasonable nexus between the classification and the object of the law. The test of temporal unreasonableness, as explained in Justice Pardiwala’s dissent seems to add a “third prong”—whether the previous two elements remain relevant over time.

This brings us back to Justice Nariman’s statement in Joseph Shine, where he wrote that Section 497 no longer conformed to “today’s constitutional morality.” The temporal unreasonableness test (though not with this name) has appeared in at least a couple of other high-profile cases in the last two decades. For example, in the decriminalisation of homosexuality case, Justice Nariman’s concurring opinion referred to John Vallamattom v Union of India (2003), where Section 118 of the Indian Succession Act, which prohibiting Christians from bequeathing their property for religious purposes, was struck down. In John Vallamattom, the Court acknowledged that subsequent events might render a provision unconstitutional due to the passage of time.

In Anuj Garg v Hotel Association of India (2007), the Supreme Court struck down a pre-Constitution law that prohibited women from being employed in establishments where liquor was consumed. While holding that discrimination “must be founded on a rational criteria”, the Court held that a classification based on societal conditions in the 20th century would not necessarily hold in the 21st century.

Justice Pardiwala on temporal unreasonableness of Section 6A

In the Citizenship Act case, Justice Pardiwala observed that the underlying object of Section 6A had evolved to a point where it no longer served its purpose and had become unconstitutional.

Section 6A(3) states that a person who entered Assam between 1 January 1966 and 25 March 1971 can become a citizen if they (a) are ordinary residents of Assam and (b) are detected as foreigners. Justice Pardiwala pointed out that the provision offers no mechanism for such individuals to voluntarily register for citizenship. This places the burden on the State to detect someone as a foreigner before the naturalisation process can begin.

Justice Pardiwala noted that the provision intended for the timely identification of migrants within the 1966-71 time frame. If this identification had been carried out, all individuals entering during the period could have been detected. Since the State did not undertake this task, many unidentified persons remained in Assam, with no voluntary mechanism for them to register as citizens.

According to Justice Pardiwala, this lack of timely identification encouraged more migrants to enter Assam after the cut-off date and become ordinary residents until they were detected. He described this system as “absurd,” noting that detected foreigners had to register within a fixed period or face deportation while undetected foreigners could continue to reside without the threat of deportation. This created unequal treatment for similarly situated individuals.

Justice Pardiwala held that these issues arose due to the passage of time. If Section 6A had imposed a temporal limit after which it ceased to apply, the provision would have served its intended purpose.

CJI Chandrachud’s disagreement with the dissent

While Justice Surya Kant’s majority opinion does not directly address Justice Pardiwala’s dissent, Chief Justice Chandrachud disagreed with the temporal unreasonableness argument. He stated that the object of Section 6A(3) was not only to identify migrants from the 1966-71 period but to provide a “long-term solution” for the issue of migration and citizenship in Assam. The provision was designed to address the larger question of whether migrants from Bangladesh could secure citizenship in India.

He emphasised that the provision must be understood within the broader context of post-Partition policies and the specific situation in Assam. Additionally, given that the process of granting citizenship takes decades, the provision could not be struck down based on temporal unreasonableness.