Analysis

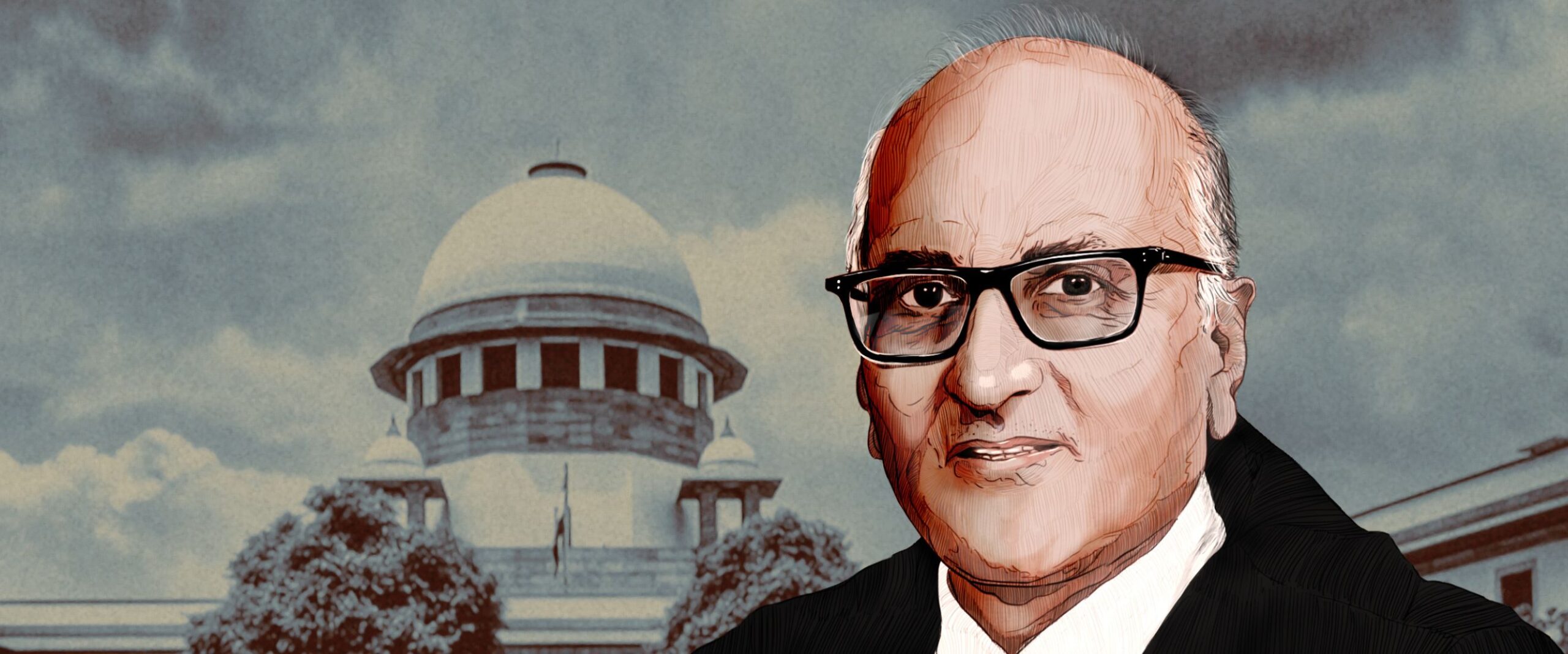

The many legacies of Justice S. Ravindra Bhat

Civil rights champion, ‘black letter’ judge, the man who shook up Indian IP jurisprudence—who was the real Justice Bhat?

On the morning of 17 October last year, Advocate Rohin Bhatt was cautiously hopeful about a judgement that the Supreme Court had promised to announce. It was five months after 10 days of intense and passionate arguments in the marriage equality case, a big day for the LGBTQI+ community. “Looking at the judges on the Bench, a lot of us believed this was the best time for us to get something out of the Supreme Court,” Rohin Bhatt said.

But it turned out to be a false dawn. Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud went first. He declared that there was no right to marry even as he directed the State to consider legislating on the right to marriage. Then, Justice S. Ravindra Bhat announced the judgement he had authored on behalf of himself and Justice Hima Kohli.

In the even and pointedly direct style he had come to be recognised for, Bhat made it clear that they had taken a position distinct from the Chief Justice’s. “We do not agree with certain premises and conclusions he recorded,” Bhat said, “We do not agree that there exists no fundamental…” Bhat stopped, realising his mistake.

It was a slip of tongue. He, in fact, agreed with the Chief about the impossibility of a right to marry and did not consider the Special Marriage Act to be unconstitutional. But he couldn’t “particularly subscribe to the characterisation of democratising intimate zones.” Essentially, Bhat could not even get on board with putting his name to the Chief’s directions to the State to protect the queer community and recognise the right to civil union.

Bhat’s judgement, as the majority opinion, would seal the petitioners’ reversal. His turn was surprising to some because he enjoyed a reputation as a sound constitutional mind. His observations in key human rights judgements had given activists reasons to tip their hat to him. Most people I spoke to for this article would reiterate that he was a judge who could never go blatantly wrong: even where his conclusions were not agreeable, the ways in which he arrived at them somehow were.

When Bhat retired two days later, some wrote about the need to look at his legacy beyond the marriage equality judgement. But others could not brush away the feeling that the waters had been irreparably muddied.

The case that marked one of the bookends to Justice Bhat’s remarkable journey in the law courts is actually a good place to start telling that story. As an advocate, he was involved in landmark cases that engaged with the most challenging dilemmas of the republic. As a judge in the Delhi High Court, he led a progressive approach in the intellectual property rights domain. After his elevation, he walked a fine line while grappling with rights issues, mostly falling on the side of the text while also stressing the need for lawmakers to expand their conception of social justice.

If one wants to avoid getting into the weeds, one can simply classify Bhat as a “black letter” judge and leave it at that. But legacies live complicated lives—many would tell me he was a man caught in a conflict between the expansive domain of rights and the often unyielding limits of the law. This mosaic also raised the question of whether he had been somewhat tinged by the political colour of his professional mentors. Ultimately, what Bhat leaves behind is a portrait of both promise and disillusion, not unlike the Supreme Court of today.

The litigation years

In 1958, Bhat was born in Mysore to a Kannadiga Brahmin family. He spent the better part of his childhood in Swarga village, in the sunny district of Kasaragod in north Kerala. In his farewell speech, he said that he was already 22 years old when electricity finally reached the village.

His father was a government employee with a transferable job. That’s why much of Bhat’s higher education was completed in north India. He did his undergraduate studies at Hindu College after finishing high school in Faridabad.

When Bhat joined Campus Law Centre in Delhi, it was amidst many stellar characters—his batchmates included three men who would become brother judges in the future: Dhananjay Chandrachud, Sanjay Kishan Kaul, and Hrishikesh Roy. Others like Parag Tripathi would be designated as Senior Advocates.

Soon after he enrolled at the bar in 1982, he started representing those who had suffered in the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. An advocate who spoke to me on condition of anonymity shared that Bhat gradually put together a practice that focussed on evidence and labour law matters.

But, even in those initial days, it was clear that he relished his interventions as a civil rights litigator. The advocate told me that he represented the People’s Union for Democratic Reforms and the People’s Union for Civil Liberties—both NGOs—in several cases.

For PUDR, for instance, he argued against the constitutionality of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act. In 2022, Justice Bhat recused himself from hearing a personal liberty matter involving activist Gautam Navlakha, who is closely associated with PUDR and has been a former secretary of the organisation. Navlakha had been in jail as an accused in the Bhima Koregaon case and had requested house custody on account of his deteriorating health.

Another thread that runs through Bhat’s career on both the bar and the bench is an interest in affirmative action. His own work as a lawyer had a way of coming back to him as a judge. In the early 1990s, he represented the petitioner, who hailed from a Gouda community, in Marri Chandra Shekhar Rao v Dean, Seth GS Medical College (1990). In that case, the Supreme Court clarified that a Scheduled Tribe candidate cannot avail reservations in a state where ST status is not recognised.

“He has taken his own arguments from Shekhar Rao and dealt with them in many of his reservations judgements,” said the advocate who spoke on condition of anonymity.

In 2022, Justice Bhat revisited Shekhar Rao to hold that the decision was applicable only to ST persons who had voluntarily migrated to a different state—those who were forced to choose a state after reorganisation must not be denied ST status. He noted that it was the duty of Parliament to provide clarity on this.

Inevitably, Bhat argued in the landmark matter of TMA Pai Foundation v State of Kerala (2003), where an 11-judge Bench held that the right of religious and linguistic minorities to administer educational institutions could not be dissolved by government regulations. In his farewell speech, Bhat said that his arguments in TMA Pai were “praised” by senior lawyers K. Parasaran and Soli Sorabjee. In October 2022, while noting that institutions “solely” concerned with education and not profit should be tax-exempt, Bhat returned to TMA Pai to emphasise that education should not be treated as “business, trade, nor commerce.”

In the late 1990s, Bhat was often involved in the flurry of litigation that tested the powers of tribunals in the Supreme Court. One of the milestone judgements from this era came in L Chandra Kumar v Union of India, where the Court ruled that the higher courts’ power of judicial review was part of the Constitution’s basic structure.

In Chandra Kumar and many of his earlier matters, Bhat assisted as a junior to K.N. Bhatt, a Senior Advocate from Karnataka, now well-known for representing ‘Ram Lalla Virajman’, the infant deity, in the Ayodhya place of worship dispute.

K.N. Bhatt, who later became an Additional Solicitor General, had reportedly spent years as a prominent pracharak of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in Karnataka. In 2010, while speaking at a programme organised by a right-wing think tank, Bhatt stated that he had refused to oppose the High Court-directed archaeological survey at Ayodhya because “you either live with your faith or die with it.” K.N. Bhatt’s allegiance to the Sangh remained deep and rewarding—in 2010, he defended the RSS leader Indresh Kumar, a key accused in the Ajmer Dargah blast.

Bhatt’s mentorship would not be an uncommon affiliation for Ravindra S. Bhat.

Mentors and their saffron affiliations

In his farewell speech, Bhat acknowledged that “the lessons learned” from K.N. Bhatt significantly shaped his approach towards “self-growth” and “perfection”. Bhatt’s flourishing practice in Karnataka meant that Bhat had a chance to connect with his roots.

After he left Bhatt’s chambers in the late 1980s, Bhat went to work with C.S. Vaidyanathan, who was later designated as a Senior Advocate and would be appointed the first Additional Solicitor General of India. In another of the kind of full circle moments that seem to recur in Bhat’s professional journey, Vaidyanathan also later argued for Ram Lalla in the Ramjanmabhoomi litigation.

In November 2019, following its win in the Ayodhya matter, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad honoured Vaidyanathan alongside other lawyers in a grand ceremony. (K. Parasaran, the then 92-year-old mentor of the Ayodhya lawyers, was also awarded. In his farewell speech, Bhat remembered Parasaran as one of the “giants” of the legal world.)

Bhat had been enlisted as an Advocate on Record seven years after his enrolment in 1989. Through the 1990s, as he built a base in both the Karnataka and Delhi legal circuits, he developed influential affiliations. A Senior Advocate with roots in Karnataka told me that Bhat became “one of the persons whom Rama Jois spotted.”

Bhat’s practice in Karnataka had brought him close to M. Rama Jois who had served as a judge in the Karnataka High Court between 1977 and 1992. After the end of his tenure as Chief Justice of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, Jois had grown close to the Bharatiya Janata Party. The year he retired, he became one of the patrons and founding members of the Akhil Bharatiya Adhivakta Parishad, the lawyers’ wing of the RSS.

Between 1998 and 2000, Bhat served as a government counsel for the state of Uttar Pradesh. Kalyan Singh’s BJP government was in power in UP at the time of his appointment. “It’s perhaps not fair to categorise him in a certain way,” said the Senior Advocate when I asked how his mentors’ affiliations might have rubbed off on Bhat. “But he is a man who has well-wishers on both sides of the political spectrum. And that should be known of him.”

The “IP judge” in the Delhi HC

Bhat was appointed an additional judge of the Delhi High Court in July 2004 and a permanent judge in February 2006. Soon after, and somewhat surprisingly, he found himself increasingly entangled with intellectual property matters.

It was a busy, exciting time in intellectual property law. The government had pushed through some amendments to align India’s IP regime with international developments. The Delhi High Court became the go-to forum for IP litigation.

Many of my interviewees confirmed that Bhat had never practised as an IP lawyer. And yet, as a judge, he was assured in the face of a dynamic, fast-moving area of law, even as others on the Bench followed the old playbook of simply holding in favour of the rightsholder.

“In those days, the rule of thumb was that on the first day, an ex-parte injunction would be granted, no matter the merits,” said T. Prashant Reddy, an IP academic who has closely followed Bhat’s work. “There was very little balance of jurisprudence.” Bhat brought about a change. Earlier, orders directed the shutting down of entire businesses and seizing of pirated devices. But Bhat called for copying hard disks and mirroring of pirated software, with the effect that small businesses did not have to entirely cease operations.

Between 2008 and 2013, Bhat presided over many high-profile cases filed by originator pharmaceutical companies against generic manufacturers, often ruling against the originator and laying emphasis on the “public interest” fallout of Big Pharma lawsuits.

In Roche v Cipla (2008), the fate of a drug for cancer treatment was at the centre of the tussle between the two corporations. Bhat brought a new, pro-public dimension into the traditional test to determine injunction. “The injury to the public which would be deprived of the defendant’s product,” he wrote, “which may lead to shortening of lives of several unknown persons, who are not parties to the suit, and which damage cannot be restituted in monetary terms, is not only uncompensatable, it is irreparable.”

In Bayer v Cipla (2009), Bhat adopted innovative methods to fast-track a patent dispute case concerning a cancer drug. He appointed two scientific experts to determine the technical questions of patent validity and infringement. He framed the issues with alacrity and went directly to trial, allowing the hearings for interim injunction to be skipped.

In Syngenta v Union of India (2009), a case concerning patenting of an insecticide, Bhat dismissed Syngenta’s argument of “data exclusivity” and approved the generic version of an insecticide. The late Shamnad Basheer, an IP expert, had then written that Bhat was “clearly not amused” by pharma companies using the courts to push for backdoor policy changes.

Sadly, Bhat’s legacy in IP matters did not endure after he left the court. “It was a poor commentary on the Delhi High Court,” an IP lawyer told me on condition of anonymity. “Sometimes the Bench wouldn’t understand that a precedent had been overruled by Justice Bhat. How much can one man do when the system has broken to such an extent?”

“In the IP bar, there is this sense that only a specialised lawyer can be a specialised judge,” Reddy said. He told me that Bhat had challenged this notion with his sharp grasp of issues and engaged adjudication. “The problem is that most specialist judges from the IP fraternity have stakes in the corporate IP nexus,” the IP lawyer told me. “So they give pro-plaintiff judgements. Bhat was not like that.”

During his tenure on the Delhi High Court, Bhat also took up administrative tasks. For several years, he was in charge of preparing the court’s annual reports. During this tenure, Bhat would visit the National Judicial Academy in Bhopal. One person who recalled his time there spoke to me about Bhat’s emphasis on “pioneering” information technology for case management and filing defects. I was told he was one of the few judges who was willing to go beyond the usual discussion on digitisation of records.

In May 2019, he was transferred to the Rajasthan High Court where he presided as Chief Justice for just over three months until he was elevated to the Supreme Court.

Top court, tough questions

Bhat’s almost four year tenure on the Supreme Court was shorter than that of his Delhi High Court contemporaries like Sanjiv Khanna and Sanjay Kishan Kaul. Some have speculated that this was because he had rubbed the government the wrong way by consistently ruling against influential pharmaceutical companies in high-stakes matters. Others saw it as a mark of impartiality. “I never saw him ideologically bound,” a senior academician said. “He has always held his ground, independent of the government. He did not curry favour from any party.”

Most senior lawyers I spoke to had only good things to say about his meticulous, patient adjudication. “He’s a tough job,” said a Delhi-based advocate who has argued high-profile matters before Bhat. “His knowledge is good in terms of history. He would ask questions out of nowhere, so we really had to be prepared.”

“You would be sure that anyone approaching his Bench would be heard,” said G. Mohan Gopal, former director of the National Judicial Academy. Gopal, who has also argued before Bhat, described him as possessing “impeccable judicial integrity.” “As a result, he was always transparent during arguments. He would engage with all arguments with an open mind.”

In the Supreme Court, Bhat would preside over several significant constitutional matters. He was on benches that heard challenges to three successive constitutional amendments—the 101st (granting the Central Government power to impose GST), the 102nd (Maratha reservations) and 103rd (reservations for Economically Weaker Sections.)

Bhat’s role in the last of these was emblematic of his judicial reputation. In 2019, the 103rd Amendment had brought in reservations solely on an economic basis, while also excluding Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe candidates from availing the benefits. Bhat was part of a five-judge Constitution Bench that upheld the reservations for the EWS. However, Bhat penned a partial dissent against the amendment for excluding the SC, ST and OBC candidates from the EWS category.

Commentators pointed out that the majority judgement violated the constitutional “code of equality” and had run against years of jurisprudence that centred backwardness on social conditions. But some petitioner lawyers I spoke to felt that this was the most they could have gotten, even from Bhat. One of them told me that Bhat and the then Chief Justice U.U. Lalit had “engaged a lot” with the petitioners. He felt that the three other judges had not engaged with the petitioners’ arguments as deeply.

“A basic-structure challenge is the most difficult test to meet under the scheme of our Constitution,” said Shadan Farasat, an Advocate on Record who argued the matter. “It is not easy to convince any judge that reservations based on economic criteria, by itself, is problematic.” Farasat remarked that most judicial minds would never accept that reservations based on economic criteria were, per se, unconstitutional. Even for some petitioner lawyers, it seems that demanding an overhaul of economic reservations was not a primary objective.

Crucially, Bhat diverged from the majority on the point that EWS reservations could exclude SC, ST and OBC persons. Farasat described this diversion as a “big leap.” “When he was convinced of a cause, he was a judge who would go to any distance,” he said.

Gopal, who argued on behalf of the petitioners, went even further. While referring to the EWS judgement as the “ADM Jabalpur moment for social justice,” the former director of Bengaluru’s National Law School likened Bhat’s judgement to Justice H.R. Khanna’s famous dissent in that case.

Khanna had held that even when fundamental rights were suspended during the Emergency, the right to move the court could not be taken away. According to Gopal, Bhat’s disagreement on the point that underrepresented communities could be denied representation through EWS reservations sought to protect the basic structure of the Constitution as Khanna would have done. Bhat’s position was put into stark relief by the majority’s opinion, which Gopal described to me as “a mortal blow to representative democracy.”

Not everyone was as impressed. Some of the experts I spoke to said that in upholding economic reservations, Bhat showcased the “judicial conservativeness” that he has been known for.

While talking to some of Bhat’s critics, I got the sense that they felt his turn in the marriage equality judgement was the final flourish of a conservative strain that had been neatly obscured through the course of his career. “In his judgement, he has gone to great lengths to argue that the structure of Article 15 cannot accommodate marriage equality,” one of the petitioner lawyers in the matter told me, “But that is frankly not what the petitioners were asking for.”

The petitioner lawyer also opined that Bhat’s judgement makes a primary argument for rejecting marriage equality by relying on personal laws, particularly Hindu law, even though the petitioners skirted around the personal law issue. “There is a certain intellectual disingenuity, and one wonders where the pushback is coming from.”

But Farasat, who also argued on behalf of a petitioner in the marriage equality case, believed that Bhat could not be singled out. “The complexity of the textual interpretation of the Special Marriage Act was such that it was difficult to work around it.”

The final day

Bhat’s final day as a judge was unconventional. Typically, the retiring judge spends the day in Court Number 1 with the Chief Justice. But with the Chief in the United States for a lecture tour, Bhat presided over his ceremonial bench along with three other judges in Court Number 2. For a ceremonial bench, it was a rather busy one. And, true to form, on his final day at work, Bhat pronounced one of his most significant judgements.

Since October 2022, Bhat’s bench had presided over the issue of the non-implementation of the 2013 manual scavenging statute. The law, which came into existence after years of resistance to manual scavenging by anti-caste activists, had remained toothless. In its 2014 decision in Safai Karamchari Andolan v Union of India, the Court had issued a strong set of directions to ameliorate the lives of manual scavengers: cash assistance, scholarships for children’s education, vocational training and housing facilities, compensation of Rs 10 lakh in case of death in a sewer.

For ten years now, Bezwada Wilson, national convenor of the Safai Karamchari Andolan, has organised against governments caring little to comply with the statute or the Court’s directions. Last year, as part of the ‘Action 2023’ campaign organised by the Andolan, hundreds across the country peacefully protested the failure of state governments in preventing manual scavenging-related deaths. “We are not asking you to give us your money, your compensation, all these things,” Wilson told me in October last year. “We have only one agenda: stop killing us.”

On his final day, Bhat had the chance to reconcile this legislative injustice in a way that was concrete.

In his order, Bhat instructed that the Central and state governments give directions for ‘full rehabilitation’ as directed in Safai Karamchari Andolan. He directed the Union to finalise the modalities for a National Survey in the next three months. He also ordered the disbursement of scholarships. The compensation amount in case of death was increased to Rs 30 lakhs from Rs 10 lakhs.

In this publication, Arvind Narrain has written about how, within the space of a couple of days, Bhat had taken polar opposite positions on the judiciary’s competence to issue directions to the State: he actively pushed it in Balram Singh (the scavenging judgement) but opposed it in Supriyo (the marriage equality judgement.)

Wilson seemed unimpressed by Bhat’s order in Balram—he told me that merely increasing compensation amounts is not going to redress the structural issues. “There are women who have been waiting for twenty years for compensation. There are no partner rehabilitation schemes, only promises,” Wilson said, “We will give ten lakhs…we will give twenty lakhs….where have they given money? Nowhere.”

Wilson also pointed to the lack of a timeline for compliance of the directions in Balram. “The government gives deadlines for everything, why have no deadlines been given for this?” For someone like Wilson who has steered the movement, the judgement came across as no more than lip service. This, too, must be considered part of Bhat’s legacy.

Many legacies

Bhat’s final two judgements in Supriyo and Balram sum up, in a way, the shadows cast in a career that was often grounded in social facts and at other times disconnected from the suffering in the field.

The energy and application with which he led IP benches in the Delhi High Court will sit next to matters where he won the hearts of lawyers arguing before him even while he denied relief to their clients. The political affiliations of his mentors exist side by side with his reputation as someone who affirmed social movements in the face of state apathy.

What stayed constant throughout his career was his efficiency and professionalism, both rare in a legal system that is known to drag its feet when convenient. Even if it is not the only one, that will be his most enduring legacy.

Masthead illustration credit: diefleadie

Corrections and Clarifications: In the context of the marriage equality judgement, an earlier version of this article quoted Bhat as writing that he “did not agree with the idea of democratising intimate spaces.” The article has now been updated to reflect the precise quote from his opinion. We regret the error.

A Trustee of the Legal Observer Trust, the entity under which SCO operates, appeared on behalf of one of the petitioners in the marriage equality case. Trustees are not involved in shaping day-to-day editorial policy and are not privy to discussions about commissioning and reporting.