Analysis

Supreme Court to rule on whether the rules of public employment can be changed mid-process

Can government employers set aside previously established procedural rules to ensure only the most suitable persons are appointed?

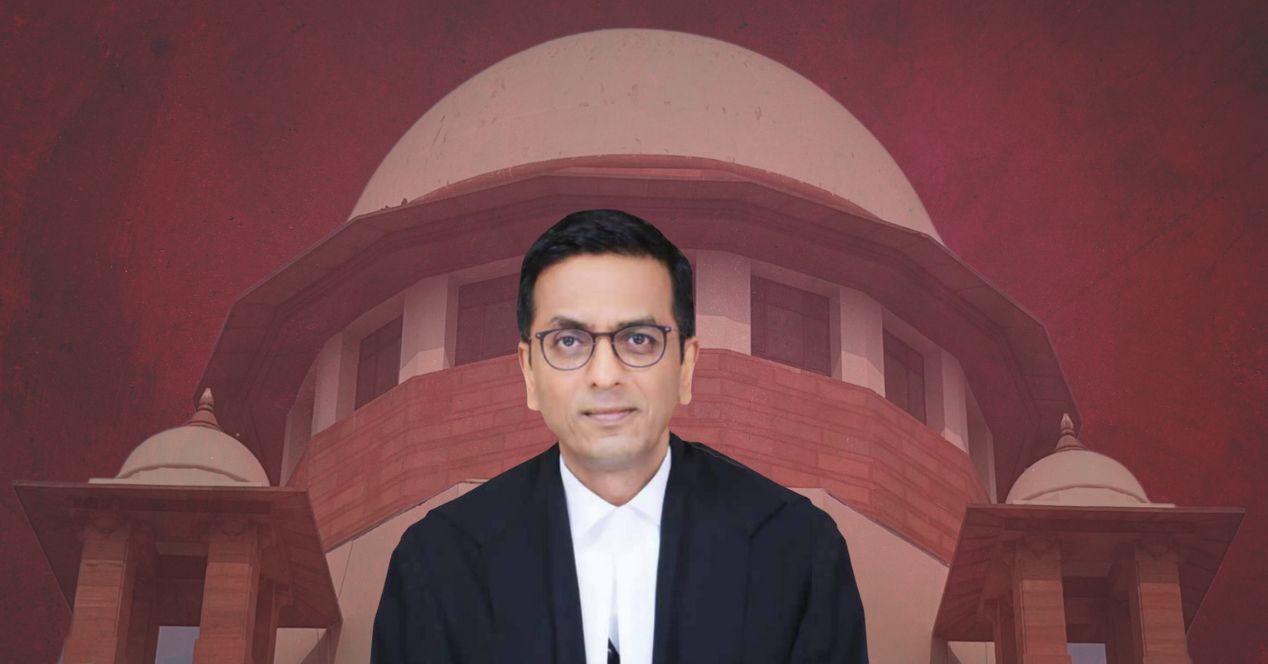

Tomorrow, a five-judge Constitution Bench will decide whether public employers can change the rules of a selection process once the process is already underway. A bench led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud had reserved judgement in the case on 18 July 2023 after three days of hearings.

What is the case about?

In 2009, the Rajasthan High Court announced vacancies for 13 translator positions. Candidates had completed a written exam and personal interview when the High Court introduced a 75 percent cut-off for the written exam. This modification resulted in the selection of only three out of 21 candidates.

Subsequently, the Rajasthan High Court dismissed an appeal by the unsuccessful candidates. They moved the Supreme Court, arguing that the new cut-off was unfair and violated equality and discrimination rights.

What is the key issue in the case?

In 2013, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court noted that while “the rules of the game could not be changed” once the game commenced, “an absolute and non-negotiable prohibition against retrospective law making is made only with reference to the creation of crimes. Any other legal right or obligation could be created, altered, extinguished retrospectively by the sovereign law making bodies.”

Changing the rules of a public recruitment process, the bench noted, was an example of retrospective law-making, which could be done if there is no “conflict with any other constitutionally guaranteed rights, such as Articles 14 and 16.”

However, the bench found that the permissibility and the scope of altering rules in employment needed scrutiny and clarification by a larger bench: “Whether such principle of law is immutable, what are those ‘rules of the game’ which cannot be changed after the game is either commenced or played, in our opinion requires an authoritative pronouncement by a larger Bench of this Court.”

The bench further noted an “authoritative pronouncement” was needed to clarify if the rules could be changed “particularly when the change sought is to impose a more rigorous scrutiny for selection.”

The case ultimately reached the CJI Chandrachud-led Constitution Bench in 2023.

What was argued in Court?

Those challenging the alteration of rules mid-process highlighted the lack of transparency, suggesting that employers could not “change the rules of the game” once it had commenced. They relied on K. Manjusree v State of Andhra Pradesh (2008).

Further, they stressed the difference between eligibility and suitability (also noted by the three-judge bench in 2013). Eligibility was the first step—all those who met the basic requirements for a role would be eligible to be included in the merit list. The second step was suitability—ensuring the most deserving or suitable candidates were recruited. While employers had the right to select the most suitable candidates, the rules at the eligibility level were prescribed in writing (in an advertisement) and could not be altered, as they could lead to a situation where eligible candidates did not make the merit list.

The Rajasthan High Court relied on State of Haryana v Subhash Chander Marwaha (1973), which allowed state governments to set higher cut-offs “in the interest of maintaining high standards.”

The five-judge bench led by the CJI dismissed individual cases of the Kerala, Manipur, Gujarat, Gauhati and Patna High Courts before reserving judgement on the question of whether changing the rules of a public employment scheme after the process had commenced was unconstitutional.

What could be the impact?

On the face of it, the case appears to be a simple clarification of whether public sector employers can amend recruitment rules after the commencement of the selection process.

But the issue before the Constitution Bench concerns an interplay between eligibility, merit and transparency. Suppose the Court holds that the rules of the game cannot be changed mid-process, there emerges an obligation on employers to notify all the rules concerning the recruitment process well beforehand and not contravene them on the grounds of “merit”.

However, if the Court holds that the rules can be altered, public employers will be able to set aside previously established procedural rules to ensure only the most suitable persons are appointed for public posts. In such a situation, even if the rules are changed to make the process more rigorous, they would still be valid.

The Constitution Bench is also tasked with setting out the extent to which exceptions can be made to that general rule that “changing the rules of the game after the game was played …is clearly impermissible”.