Analysis

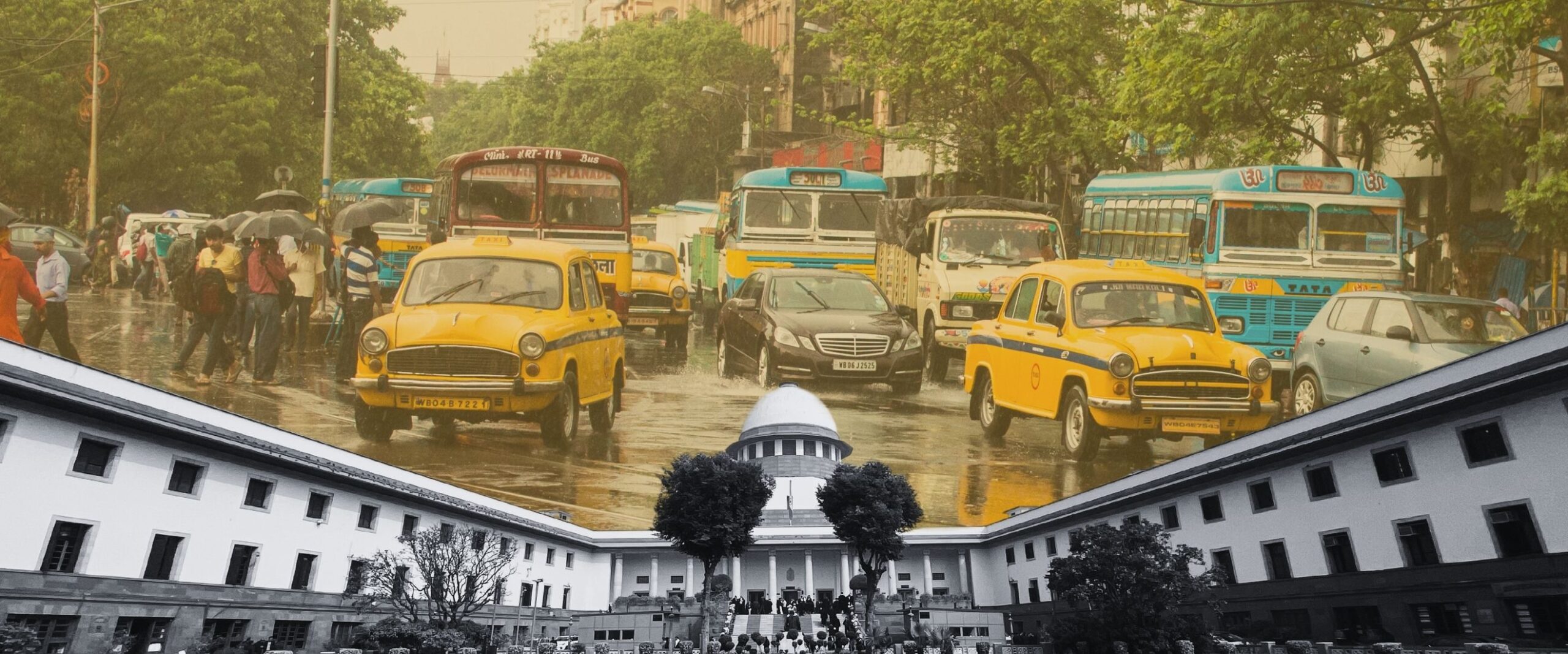

Supreme Court to decide if an LMV licence holder can drive a ‘Transport Vehicle’

The outcome will likely impact the livelihoods of gig workers who use their LMV licence to transport people and things

Tomorrow, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court will deliver judgement on whether a person licenced to drive a ‘light motor vehicle’ (LMV) is automatically entitled to drive a ‘Transport Vehicle of Light Motor Vehicle Class’ with unladen weight of less than 7500 kg”. The bench heard arguments in this case, including contentions on safety and livelihood, over seven days since July 2023.

The issue was referred to a Constitution Bench in March 2022 by a three-judge bench which found that the 2017 decision of the Court in Mukund Dewangan v Oriental Insurance Company Limited had “not noticed” some provisions in the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 (MVA) while holding that a transport vehicle less than 7500 kg would be an LMV.

Though the case first centered on safety and regulatory issues, it evolved into taking into account the livelihood of tens of thousands of gig workers who drive LMVs for transportation purposes.

The road so far

In Mukund Dewangan, the Supreme Court was asked to decide if a person holding a licence to drive an LMV (under Section 10(2)(d) of the MVA) would need a separate licence to drive a transport vehicle (under Sec. 10(2)(e) of the MVA) which was less than 7500 kg before any goods were loaded on it. A three-judge bench held that “a transport vehicle and omnibus, the gross vehicle weight of either of which does not exceed 7500 kg, would be a light motor vehicle.”

In March 2022, in Bajaj Allianz General Insurance v Rambha Devi, several insurance companies approached the Court, contending that Mukund Dewangan was wrong in allowing LMV licence holders to drive a transport vehicle. They claimed both kinds of vehicles were considered as starkly different under the MVA. For instance, the age of eligibility to acquire an LMV licence is 18, whereas it is 20 for a transport vehicle. Another difference: an LMV licence is valid for 20 years but a licence to to drive a transport vehicle is effective for three years (one year if the vehicle is transporting dangerous or hazardous goods). The two types of licences also require different degrees of training to be undertaken by the drivers.

A three-judge bench of (then) Justice U.U. Lalit, S.R. Bhat and P.S. Narasimha referred the case to a larger bench to review Mukund Dewangan. The case was listed before a five-judge bench comprising Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, and Justices Hrishikesh Roy, P.S. Narasimha, Pankaj Mithal and Manoj Misra.

What does the law say?

The appellants relied strongly on the legislative framework outlined in the MVA, pointing out all the instances where LMVs and transport vehicles were considered to be different. First, they argued that the very mention of “transport vehicles” despite there being a mention of LMVs meant that the law considered both to be separate types of vehicles.

Next, they argued that the eligibility criteria for both were different, with LMVs having a lower threshold. Apart from the higher minimum age, applicants of a licence for driving a transport vehicle also require a medical certificate attesting to their physical fitness and a distinct certificate issued by a driving school. Further, the Central Motor Vehicles Rules, 1989 sets out a separate syllabus for transport vehicle licences, which includes 30 days of extra training and modules on “fire fighting, first aid, and public relations.”

The MVA, however, does cause some confusion in terms of definition. It defines LMVs as a “transport vehicle or omnibus the gross vehicle weight of either of which or a motor car or tractor or road-roller the unladen weight of any of which, does not exceed 7500 kilograms.” The Bench agreed that while this is a type of categorisation, the licence regime did not rely on this.

A transport vehicle is defined as a “public service vehicle, a goods carriage, an educational institution bus or a private service vehicle.” Based on this, appellants argued that the MVA classifies vehicles not by weight, but by usage. Petitioners argued that when read comprehensively, it was clear that LMV licence holders did not automatically become eligible to drive transport vehicles.

The fallout of allowing LMV licence holders to drive transport vehicles, appellants argued, was that drivers without training end up driving vehicles containing people and goods. The implication of this, for instance, was that a person with a car driving licence could drive a road roller, endangering many.

Livelihoods and the social impact

While insurance companies, the Union government and organisations such as Society Against Drunken Driving all agreed that Mukund Dewangan required reconsideration, they acknowledged the issues around overruling the judgement without a clear road map.

Some insurance companies pointed out that it was unclear whether insurance policies taken by LMV holders would cover accidents that occur when they were using their vehicles for transport purposes. Would all LMV licence holders now require fresh training and new licences to drive vehicles for transport purposes?

The bench pointed out that the lakhs of drivers engaged in driving commercial vehicles based on Mukund Dewangan could be “completely put out of their livelihood.” “The easiest thing is to interpret the law and come to the conclusion that Dewangan was wrong,” CJI D.Y. Chandrachud said, “but it’s not that simple.”

Recognising its limitations in making policy, the Court said that it could not “decide issues of social policy in a Constitution Bench.” It directed the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways to review the fallout of overturning Mukund Dewangan. It asked the Union to look at the matter “holistically”, considering safety, livelihood, insurance implications and the changing landscape of the transport industry.

Stakeholder consultations and delays

The Union government informed the Court that instead of looking solely at the issues raised by this case, they would conduct an overall review of the MVA. In November 2023, the Union told the Court that the consultative process required for such an undertaking would be prolonged, particularly since ‘motor vehicles’ is a subject on both the Union and State Lists and all the state governments would have to be consulted.

Disinclined to allow long consultations, the Court directed that a completed road map must be submitted by 17 January 2024. When the day arrived, the Attorney General submitted that a draft of a committee report had been filed and that he required “some time to examine it.” The Court scheduled the next hearing for 16 April.

On 16 April, the Attorney General submitted a short note on the amendments the Union would introduce. He informed the Court that the biggest change was the introduction of two classes of LMVs—LMV 1 and 2—which could accommodate the use of LMVs for transport purposes. He sought an adjournment till the last week of July so that the amendment could be proposed before the newly constituted Parliament following the 2024 General Elections.

Finally, on 21 August, the Court decided to close the hearing before the amendments were brought in. If the court had waited, it would have to re-hear the entire case, as the winter session of Parliament would take place after CJI D.Y. Chandrachud retires in November, changing the composition of the bench. The Court reserved judgement on the same day.