Analysis

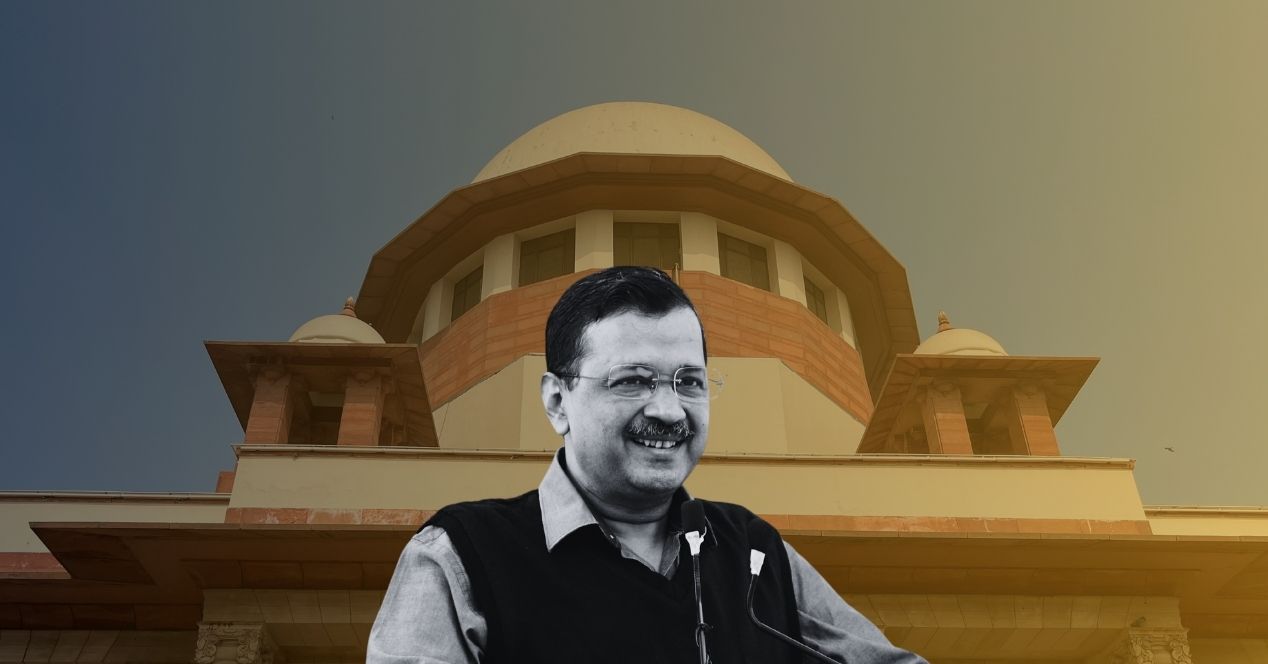

Supreme Court reserves judgement in Arvind Kejriwal’s plea for bail from CBI arrest

70 days after his arrest by the CBI, Kejriwal relied on three favourable bail orders in his ED case to argue for interim bail

Today, a Division Bench of Justices Surya Kant and Ujjal Bhuyan reserved judgement in Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s plea seeking bail from his arrest by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The CBI arrested Kejriwal for alleged corruption in the Delhi Liquor policy scam on 26 June, two weeks before he was granted interim bail from his arrest by the Enforcement Directorate. It was alleged that the policy was enacted by the Kejriwal-led Delhi government to favour specific liquor manufacturers and traders in the liquor business.

Senior Advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi appeared for Kejriwal. Additional Solicitor General S.V. Raju argued for the CBI.

Untangling the maze of bails and arrests

The CBI’s arrest was upheld by the Delhi High Court last month, on 5 August. The High Court reasoned that there was no malicious intent behind his arrest. It refused to grant bail to Kejriwal, suggesting that he should approach a Sessions Court. The CBI was investigating charges of corruption under the liquor policy scam. In the meantime, the ED was running a concurrent investigation looking into accusations of money laundering.

The ED had arrested Kejriwal in March 2024. Since then, the top court has granted interim bail to Kejriwal on two occasions. First, he was granted interim bail for 21 days to campaign for the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections. Second, he was ordered to be released on 12 July until the legality of his arrest by the ED is decided by a larger bench of the Supreme Court. By the time the second interim bail order was pronounced, Kejriwal was already arrested by the CBI. Therefore, he was never released. Moreover, a Trial Court order granting bail to Kejriwal in the ED case was stayed by the Delhi High Court a day before the CBI arrested him from Tihar jail.

In today’s hearing, Singhvi challenged the High Court’s order upholding Kejriwal’s arrest and denying him bail. The CBI opposed the bail plea arguing that Kejriwal should approach a Sessions Court instead, as suggested by the High Court.

Singhvi: Kejriwal was arrested two years after CBI began investigation

Singhvi argued that Kejriwal’s arrest by the CBI was an “insurance arrest” to keep him in custody. He highlighted that Kejriwal was arrested two years after the CBI filed its earliest First Information Report (FIR) in August 2022. He also pointed out that the FIR made no mention of Kejriwal. Singhvi went on to submit that the only other time the CBI took interest in Kejriwal was in April 2023 when he was interrogated for nine hours. He claimed that the CBI relied on statements made by Magunta Reddy in January 2024. Reddy is an approver and witness in the Liquor Policy Scam and a member of the Lok Sabha from the majority Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance.

Pushing his “insurance arrest” narrative, he claimed that the CBI had shown no intention to arrest Kejriwal until two favourable bail orders were issued (first interim bail by the top court and Trial Court Order). “The CBI suddenly wakes up and moves an application to interrogate the petitioner [Kejriwal] under [Section] 41A?” Under Section 41A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, a police officer can issue a notice of appearance of a person before them. If the person does not comply with the appearance notice, they are open to the risk of arrest. Singhvi claimed that a notice under Section 41A was restricted to instances where the police officer does not intend to arrest a person. The application to interrogate was also not provided to Kejriwal, he said. Kejriwal was then arrested within a day of interrogation.

The reasons for arrest, Singhvi said, did not conform with Section 41 of the CrPC. Section 41 deals with arrest without a warrant. In particular, he highlighted Section 41(b)(ii)(b), (c) and (d) under which an arrest without a warrant can be made for the purpose of proper investigation of an offence, preventing the tampering of evidence and inducing other witnesses.

Singhvi claimed that the CBI arrested Kejriwal for non-cooperation and intention to derail the investigation. These were not grounds to arrest. For the CBI, he remarked, anything short of a confession amounted to non-cooperation. “When they say he is not cooperating…they actually mean he is not declaring himself guilty,” he said. Lastly, Singhvi stated that Kejriwal was already in custody when he was arrested by the CBI making it impossible for him to induce any witnesses.

Singhvi: How is it easier to get bail under the PMLA?

Perhaps the strongest arrows in Kejriwal’s quiver were the three favourable release orders by the Supreme Court and the Trial Court under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA). Securing bail under Section 45 of the PMLA, Singhvi said, was a challenging affair. He quipped that despite this, Kejriwal got bail under the “stringent” PMLA law, but was struggling to get bail from a CBI arrest, though he passed the “triple test”. The triple test dictates that if the accused is not a flight risk, will not influence witnesses and tamper evidence, he must be granted bail.

Kejriwal, Singhvi argued, ticked all the checkboxes because it would be difficult for a sitting Chief Minister to be a flight risk. Further, he highlighted that most witnesses in the case, including former Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia, were released on bail. Lastly, with so much evidence and documentation secured online, it was unlikely that Kejriwal could tamper with them.

Directing Kejriwal to approach a Trial Court for bail, Singhvi submitted, would be engaging him in a game of “snake and ladder.” The phrase “snake and ladder” was intentionally picked from a Division Bench order by Justices B.R. Gavai and K.V. Viswanathan which granted bail to Manish Sisodia who was also arrested under the same Liquor Policy case. The ED and CBI had proposed that Sisodia approach a Trial Court for bail rather than the Supreme Court.

Raju: Kejriwal is “privileged”, “extraordinary” and “special”

Raju attacked the “snake and ladder” argument by pointing out that Sisodia and other accused in the case had climbed the Trial Court ladder to eventually knock on the doors of the Supreme Court. Kejriwal had directly approached the Delhi High Court for bail because he was an “extraordinary person.” The CBI, he continued, had objected to a bail plea in the High Court.

Justices Kant and Bhuyan pointed out that the High Court should have made a decisive decision “then and there” and directed Kejriwal to approach the Trial Court. Raju insisted that Kejriwal should have provided a cogent reason for approaching the High Court for bail instead of a Trial Court. The only unique feature in Kejriwal, according to him, was that he was a “privileged person.”

The CBI, through Raju, repeated their preliminary objection, stating that the bail plea should be heard by a Trial Court first. “There are no special persons as far as law is concerned,” he asserted.

Raju also submitted that Kejriwal directly approached the High Court before the first charge sheet was filed in the case. The charge sheet, he said, contained details that proved his prima facie guilt. The attempt, according to him, was to secure bail before the charge sheet is put on record. In his rejoinder arguments, Singhvi claimed that no person would be able to apply for bail in instances where charge sheets are yet to be filed. “If this submission is correct the prosecution will decide how and when the charge sheet is filed. No provision of law in 75 years has suggested that,”Singhvi exclaimed.

Raju: No violation of Sections 41 and 41A

Raju argued that a notice of appearance under Section 41A was not necessary for persons who were already under custody. There was no requirement to inform Kejriwal in advance before questioning him. He stated that there was a “deemed notice” when the investigating officer met with the jail authorities. Justice Bhuyan pointed out that this was a “regressive interpretation” of Section 41A.

Raju then highlighted that Section 41 was not violated either. The remand application contained the grounds of arrest and they were compatible with the grounds included under Section 41 (b)(ii)(b), (c), and (d). The remand application was provided to Kejriwal which contained the grounds of arrest in writing.

The bench reserved judgement in the case after a full day of arguments.