Analysis

State Election Commissioners Should be Independent, Non-State Officers, Justice Nariman Holds

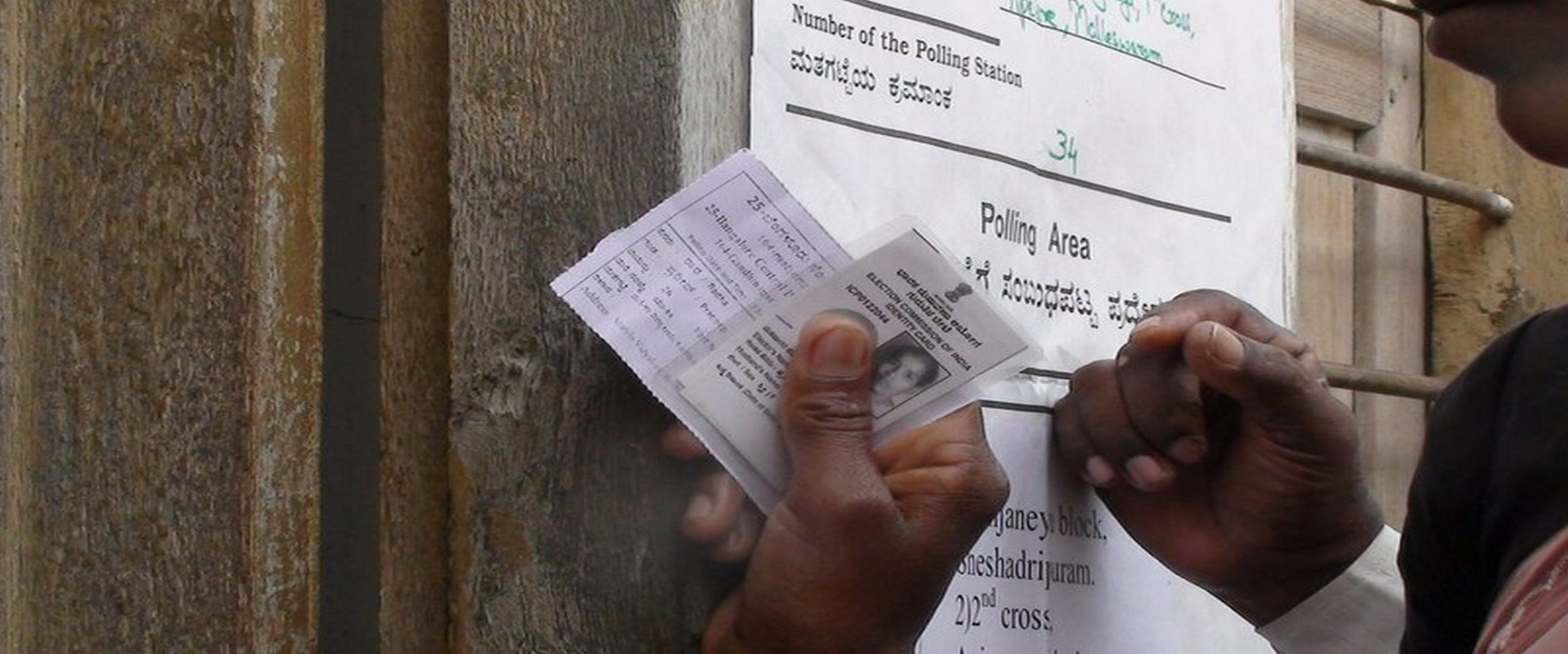

Court holds that State Election Commissioners must be independent and must not be officers who are employed by the State.

The Supreme Court this month, affirmed that State Election Commissioners should be independent. Further, that the bar against interfering with elections would not apply if the Court was acting in ‘furtherance of the election proceedings’. The judgment in State of Goa v Fouziya Imtiaz Shaikh was delivered by Rohinton Nariman J on behalf of the three-judge bench, with Gavai and Hrishikesh Roy JJ.

11 municipalities in Goa were due to end their term on 4 November 2020. Elections were postponed to 18 January 2021 because of the pandemic. On January 14th, however, this was postponed further to a date as determined by the State Election Commission. On February 4th, the State of Goa amended the Goa Municipalities Act, 1968 (‘the Act’). This allowed the Government to issue a notification for reservation of wards ‘at least seven days’ before the notification of dates for the election. On the same day, the Director of Municipal Administration issued a notification for reservations in the 11 municipalities.

This notification was struck down on three grounds by the Bombay High Court. The State of Goa appealed the decision before the Supreme Court. First, the number of seats reserved for women was less than one-third. The State of Goa had argued that if one-third of the total number of seats was a fraction, they had ignored the fraction and rounded it down. The fraction would be accommodated for in the next election, such that over three elections the total number of seats reserved for women would be equal to the number of seats in one election. The petitioners pointed out that the Constitution, as well as the Goa Municipalities Act, 1968, required the number of seats reserved to be ‘not less than’ one-third. This meant the fraction could not be ignored in any single election. It must always be ‘rounded up’. Second, the Bombay High Court took suo moto cognisance of the fact that the number of seats reserved for OBCs was also 20-25%, instead of 27% as the Act required. Third, the Act mandated the seats to be ‘rotated’ every year ‘having regard to the concentration of the population’. These requirements were not met.

When the notification was challenged before the Bombay High Court, the State of Goa had failed to mention that it was decided that elections would be held on March 20th 2021. So the High Court did not hear the matter urgently. When the date of the hearing came on February 22nd, that very morning, the State Election Commissioner issued a notification at 9 am, starting the process of elections. Notably, the Commissioner was also the Law Secretary, a member of the executive civil service.

The State of Goa then argued that their notification was protected on two grounds. First, the bar against questioning laws on the delimitation of seats in Article 243ZG. The Supreme Court in Meghraj Kothari had held that notifications were protected by this absolute bar, the State submitted. Second, they relied on the principle that once an election had begun, the Court should not interfere with it. This principle was drawn from a variety of cases beginning from NP Ponnuswami.

Nariman J took great issue with this sequence of events. He noted that many States issued these notifications with little time for challenges. Affirming the Bombay High Courts decision, he held that the number of seats reserved for women had to be ‘not less than one-third’ in each election. He also affirmed that the State Government had to comply with the mandate to reserve 27% seats for OBCs and rotate the reserved seats between elections.

The constitutional bar could not be used to protect this notification. The case of Meghraj Kothari which the government relied on could be differentiated, as was done in Anugrah Narain Singh. In the former, the notification that had announced delimitation of seats was given the status of law by statute. Unless there was some statute that gave notifications such a status, then notification would not be protected from judicial scrutiny. Further, when the elections have already been delayed, and the issue is one of ensuring the Constitution is complied with, the Courts were acting ‘in furtherance of the election’. There was no question of interfering with elections in this case.

Nariman J strongly criticised an officer employed by the State being additionally appointed as the State Election Commissioner. The Commissioner was meant to be a constitutional, independent office. Further, the fact that elections were started on the day of the hearing was an act of ‘malice in law’. The Court reiterated that this was unconstitutional, and no State could appoint a Commissioner who was an officer of the State.

The Goa elections are finally scheduled to be held on April 30th 2021, on the order of the Court. The judgment seems to balance judicial review of election proceedings with executive deference. Judicial interference should be grounded in the need to ensure adherence to the Constitution.