Channel

Section 6A of the Citizenship Act: Judgement Explainer

We bring you the key highlights of the decision upholding Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955.

Transcript:

Hello everyone!

Welcome to SCO Explains!

I am Advay Vora and today we will be discussing the recent Constitution Bench decision upholding Section 6A of the Citizenship Act.

On Thursday last week, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court, in a 4:1 majority, upheld the constitutionality of the law.

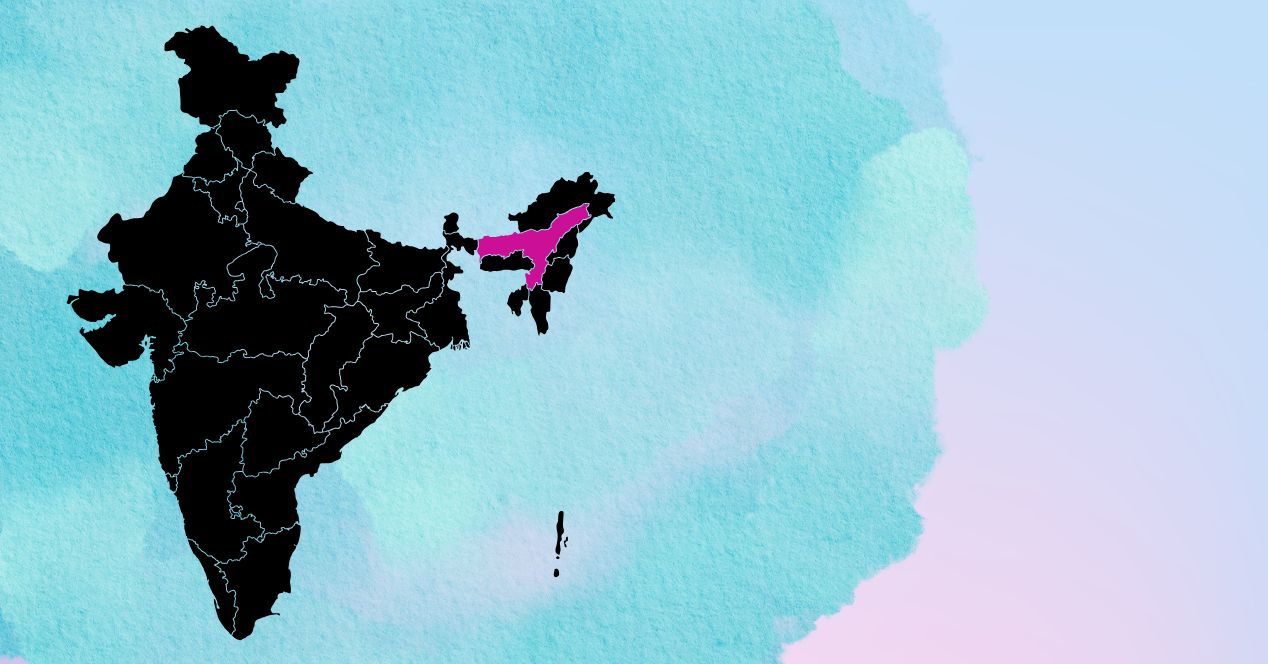

Section 6A was inserted in 1985 as a result of the Assam Accord. The agreement between student unions protesting the influx of immigrants and Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress government was the culmination of a turbulent period in the state’s history.

Section 6A was a legislative compromise. It created two categories: For those who entered Assam before 1 January 1966 and another for those who entered between 1st January 1966 and 24th March 1971, the day before the Pakistani army initiated a military crackdown to suppress the Bengali national movement.

Both categories were given citizenship, with the second category being denied voting rights for ten years from the date of their detection as a “foreigner.”

One of the contentions of the petitioners was that the provision violated an existing cutoff date for migrants who came from East and West Pakistan during the partition.

East Pakistan is what we know now as Bangladesh.

CJI Chandrachud’s concurring opinion explains this.

Article 6 of the Constitution provides that anyone who migrated to India on or after 19th July 1948 would be deemed as a citizen on the date of the Constitution’s commencement, so long as they were able to prove six months of residence preceding the date of the application for registration as a citizen.

However, many migrants entered India from Pakistan after 26th July 1949, which could be the last date an individual could have entered the country and satisfy the six-month residency requirement of Article 6.

CJI Chandrachud said that Section 6A was designed to accommodate those migrants.

The petitioners’ contentions ranged from violation of cultural rights by ‘foreigners’ to the duty of the Union to intervene to settle the ‘internal disturbances’ the migration had caused.

The Court dismissed them, asserting that arguments for cultural exclusivity undermine the principle of fraternity enshrined in the Constitution.

Further, the demand for Union intervention could lead to disastrous consequences as that would result in citizens demanding the Union to invoke its emergency powers.

One argument, however, resonated with the bench. The issue of the weak implementation of Section 6A.

The majority opinion, authored by Justice Surya Kant, ordered a Court-monitored implementation of Section 6A aimed at identifying and expelling migrants who entered after the March 1971 cutoff date.

Justice J.B. Pardiwala based his dissent on this issue.

He pointed to the failings of Section 6A (3) which granted citizenship to migrants from the 1966 to 71 period, but barred them from voting for ten years.

This provision, he wrote, was designed to address concerns around the electoral impact of recent migrants.

He observed that the Government hadn’t identified those who entered during that period in a timely manner.

Therefore, with the passage of time, the provision does more harm than good, as the weak implementation acts as a “vortex” that attracts other illegal migrants.

He recommended the prospective striking down of Section 6A.

The effect of this would be that citizenship granted prior to the judgment would remain unaffected, but those who had not yet been identified as citizens would be treated as illegal.

For a detailed summary of the 407-page judgment, be sure to check out our judgement summary.

You can also refer to our judgement matrix that breaks down the key takeaways of the judgement in a tabular form.

Thank you for watching!

See you soon!