Analysis

SC bats in favour of accused’s liberty despite High Court stay on discharge

The top court noted that discharge is on a higher pedestal than acquittal and cautioned appellate courts against restoring arrests lightly

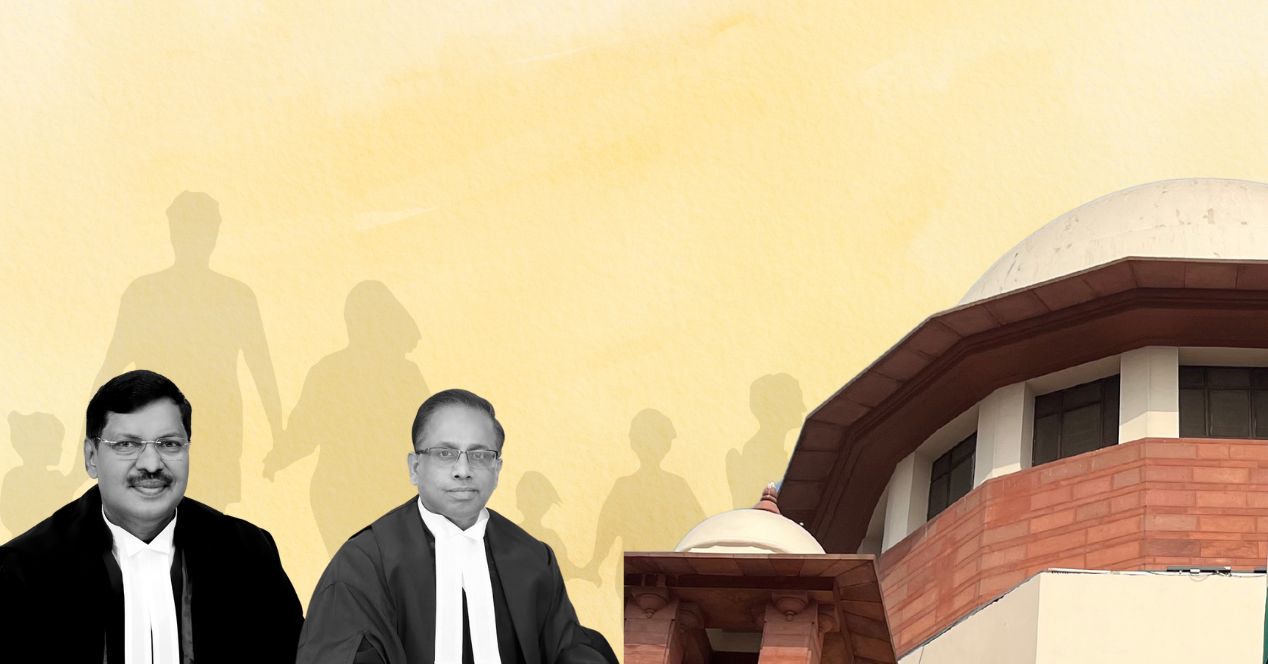

On 28 February, in Sudershan Singh Wazir v State (NCT of Delhi), a Division Bench of the Supreme Court comprising Justices A.S. Oka and Ujjal Bhuyan clarified the law on discharge orders issued by trial courts at the threshold. It did so while setting aside an Order of the Delhi High Court, which had interpreted its ex-parte stay on one such discharge as restoring the arrest of the accused and revival of trial against him.

The appellant in this case was a Sikh leader and former president of the Jammu and Kashmir State Gurdwara Parbandhak Board. He was accused in the September 2021 murder of former National Conference MLC Trilochan Singh Wazir in Delhi. In November 2024, Justice Anish Dayal of the Delhi High Court had allowed the application filed by the prosecution seeking his surrender, following the previous stay on discharge issued by the High Court.

An order of discharge is passed when there is no sufficient material to proceed against the accused. Wazir had been discharged by the trial court on 20 October 2023, after which the Delhi Police challenged the Order before the High Court.

A Single Judge of the Delhi High Court stayed the discharge order on 21 October 2023, while issuing notice in the revision application.

Discharge is ‘paused’ by the stay: Delhi High Court

On 4 November 2024, Justice Dayal directed the appellant to surrender before the trial court. He was granted liberty to apply for bail thereafter. Justice Dayal had reasoned that the benefit of securing release, pursuant to the discharge order, could not subsist for Wazir as the other accused were still in custody. While the discharge was not non est by virtue of the stay, the High Court took the view that it had been “paused” by the stay. Since Wazir was not in custody, the High Court noted that it could take steps to rectify the situation and ensure that its orders were both practically and judicially implemented.

The High Court held that there is no provision which denudes the power of the high court or prohibits it from securing custody while adjudicating a challenge to discharge—a successful challenge would require that the accused be placed back in custody and the trial would recommence.

Order in Tirki was due to absence of sanction and not investigation of merits

Section 390 of the CrPC (the corresponding section 431 of Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS), 2023), dealing with arrest of accused in appeal from acquittal, came in for interpretation in this case. Relying on the Constitution Bench judgment in State of Uttar Pradesh v Poosu (1976), the Supreme Court noted two objects of Section 390: (a) the accused must be available for undergoing sentence if acquittal turns to conviction on appeal; and (2) securing the presence of the accused at an appeal hearing. So the Supreme Court unequivocally agreed that there is a power vested in the High Court to arrest an acquitted accused and bring him before the trial court.

Where the Supreme Court differed from the High Court is in finding that an order committing an acquitted accused to custody should be passed only in rare and extreme cases and by way of exception. In ordinary circumstances, the respondent should be entitled to bail and liberty. “It is well-settled in our jurisprudence that bail is the rule, and jail is the exception,” the Supreme Court noted, using its oft-repeated phrase.

In its November 2024 direction, the Delhi High Court had relied on State of Maharashtra v Mahesh Kariman Tirki (2022), where the Supreme Court had held that the appellate court may suspend the order of acquittal or discharge under Section 390.

But the Supreme Court sought to distinguish Tirki, where the Bombay High Court’s order of discharge had only been based on the absence of sanction. The High Court had not gone into the merits of the conviction by the trial court. The Supreme Court had passed a drastic order of stay in this case while issuing notice on SLP against the order of discharge. The Supreme Court, therefore, did not consider Tirki relevant to the present matter.

Discharge is on higher pedestal than acquittal: Supreme Court

The Delhi High Court said that in the case of acquittals on appeal, it was well established that if there were two views possible, the view taken by the trial court should not be disturbed. However, a similar judicial view was not available for cases of discharge. Justice Dayal noted that Justice Mahajan, who stayed the discharge order in October 2023, had looked into the present case—one of heinous murder—and had “brought into question the very exercise by the ASJ in assessing the evidence pre-trial.”

But the Supreme Court, on its part, reasoned that the order of discharge is on a higher pedestal than an order of acquittal. When a discharge order is passed, the person ceases to be an accused. The order staying the discharge is a very drastic one which has the effect of curtailing or taking away the liberty granted to the accused.

The Supreme Court used another principle to explain why the High Court could not have stayed discharge by the trial court. An interim order of stay, the Supreme Court explained, can be granted pending disposal of the main case only if it is in the aid of final relief sought. If the discharge order is ultimately set aside in the revision application, the accused has to face trial. Therefore, the order staying discharge by way of interim relief cannot be said to be in the aid of final relief, the bench held.

The Supreme Court also found fault with the High Court staying the discharge order ex parte. A discharge order can be stayed only after giving an opportunity of being heard to the accused. While granting the stay, the court must mould the relief so that the trial does not proceed against the discharged accused. If the trial against the discharged accused proceeds before the revision application is decided, the final outcome would become fait accompli, the Supreme Court pointed out.

In its decision in Parvinder Singh Khurana v Directorate of Enforcement (2024), also authored by Justice Oka, the Supreme Court dealt with the power of the Court to stay the order granting bail pending final disposal of cancellation of bail proceedings. When an undertrial is ordered to be released on bail, his liberty is restored, which cannot be easily taken away. The Supreme Court had underlined that the undertrial is not a convict.

“It cannot be said that if the stay is not granted, the final order of cancellation of bail, if passed, cannot be implemented. If the accused is released on bail before the application for stay is heard, the application/proceedings filed for cancellation of bail do not become infructuous. The interim relief of the stay of the order granting bail is not necessarily in the aid of final relief,” Supreme Court had held in that case.