Analysis

Right to Privacy: Court in Review

An analysis of the history of right to privacy under Article 21 of the Constitution.

1948

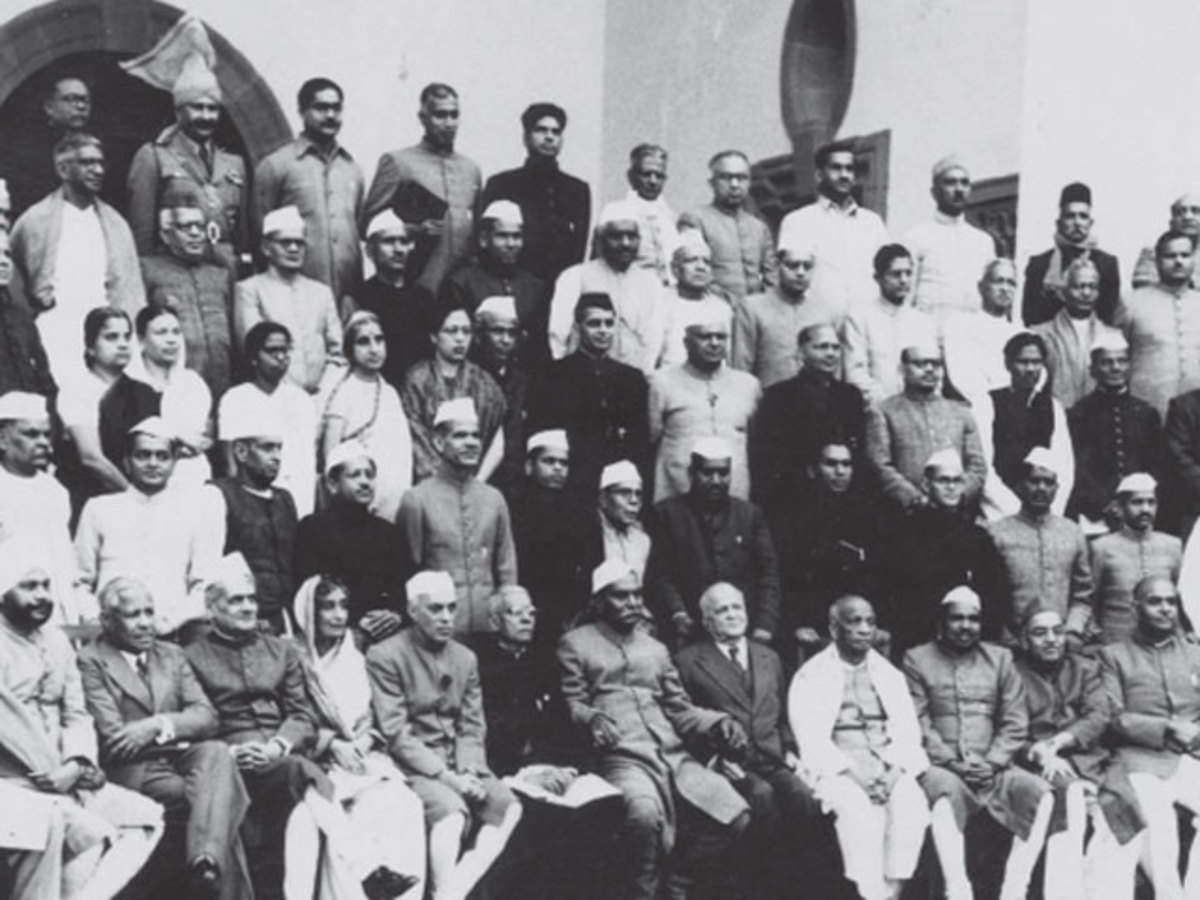

Constituent Assembly Debates

The first attempt to protect the privacy of an individual against unreasonable state interference was in the Constituent Assembly when Mr. Kazi Syed Karimuddin moved an amendment to protect individuals from unreasonable search-and-seizures, on the lines of the American and Irish Constitution. Notably, although Dr B. R. Ambedkar pointed out that this clause is present in the Criminal Procedure Code, he accepted the amendment, calling it a ‘useful proposition’ which must be ‘beyond the reach of the legislature’. However, the right to privacy did not find a definite and explicit place in the Constitution.

1954

MP Sharma v Satish Chandra

The case related to search and seizure of documents of some Dalmia group companies following investigations into its affairs. Following an FIR, the District Magistrate issued warrants, and searches were consequently conducted. In writ petitions before the Supreme Court, the constitutional validity of the searches was challenged on the grounds that they violated their fundamental rights under Articles 19(1)(f) and 20(3) — protection against self-incrimination. In M. P. Sharma vs. Satish Chandra, the 8-judge bench of the Supreme Court held that the drafters of the Constitution did not intend to subject the power of search and seizure to a fundamental right of privacy. They opined that the Constitution does not include language similar to the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution, and found no justification to import the concept of a fundamental right to privacy in search-and-seizures, through what they called a ‘strained construction’.

1962

Kharak Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh

The right to privacy was invoked in this case to challenge the surveillance of an accused person by the police. Kharak Singh was arrested for dacoity but was released due to a lack of evidence. The Uttar Pradesh Police subsequently brought him under surveillance, which was allowed under Chapter XX of the Uttar Pradesh Police Regulations. Kharak Singh then challenged the constitutional validity of Chapter XX and the powers it conferred upon police officials, as it violated his fundamental rights under Article 19(1)(d) (right to freedom of movement) and Article 21 (protection of life and personal liberty). The 6-judge bench held that domiciliary visits at night was unconstitutional, but upheld the rest of the Regulations. More importantly, the bench held that the right of privacy is not a guaranteed right under the Constitution.

1975

Govind v State of Madhya Pradesh and Another

Govind challenged the validity of the Madhya Pradesh Police Regulations related to surveillance, including domiciliary visits, similar to Kharak Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh. Govind alleged false accusations against him on the basis of which he was put under surveillance by the police. The Supreme Court dismissed the petition but advised reform in the Madhya Pradesh Police regulations and observed that they were ‘verging perilously near unconstitutionality’.

2017

Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India

On August 24th 2017, a 9 Judge Bench of the Supreme Court delivered a unanimous verdict in Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India and other connected matters, affirming that the Constitution of India guarantees to each individual a fundamental right to privacy. Although unanimous, the verdict saw 6 separate concurring decisions. Chandrachud J authored the decision speaking for himself, Khehar and R.K. Agarwal and Abdul Nazeer JJ. The remaining 5 judges each wrote individual concurring judgment