Analysis

Remission for convicts only if they respect the rule of law

The Supreme Court called out the convicts' abuse of process in the Bilkis Bano case

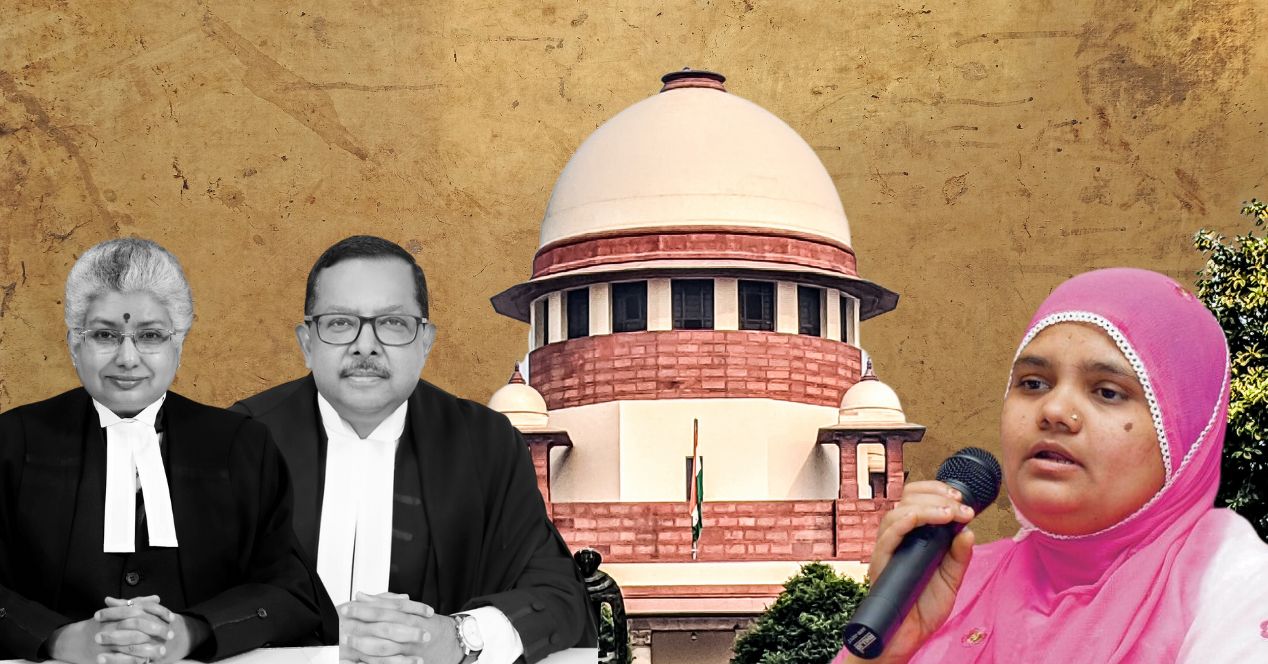

On 8 January, a Bench of Justices B.V. Nagarathna and Ujjal Bhuyan quashed the remission orders that led to the release of 11 convicts in the Bilkis Bano case.

The matter’s procedural history had enough twists and turns to provide a narrative spine. The story that emerged was one of entitlement and executive collusion. But what was fascinating to me as a court reporter was the way these dots emerged over the course of the hearings. The oral and written submissions reiterated the beauty of advocacy and adjudication, the need to read the lines and between them to expose the rotten core of the matter.

Let me give you a quick run through. The judgement centred on the abuse of process by the Gujarat government and convict Radheshyam Bhagwandas Shah. Radheshyam approached the Supreme Court in March 2022 with a request to direct the Gujarat government to consider his remission under the cancelled 1992 Gujarat Remission Policy. On 13 May 2022, the Supreme Court accepted his prayer and issued a writ of mandamus.

To begin with, the initial hearings before Justices K.M. Joseph and Nagarathna were repeatedly postponed due to procedural delays and failure to send notices to convicts, who were missing. Justice Joseph identified these as tactics to ensure that his Bench does not hear the case until he retires. (Justice Joseph had a reputation for decisions that may not have pleased the executive.)

Then, there was the squabble about fine payment. Senior Advocate Vrinda Grover argued that the remission was illegal because the convicts’ fines of Rs. 34,000 were yet to be paid. A few days later, Senior Advocate Sidharth Luthra informed the Court that the fines were paid—a whole 15 years after the convictions.

On the issue of the appropriate government, Advocate Rishi Malhotra, appearing for Radheshyam, revealed that the opinion of the presiding judge in Maharashtra was sought before granting remission. This was baffling because the Additional Solicitor General S.V. Raju had told the Court that the Maharashtra judge was never consulted.

The Bench connected many of these dots to conclude that Radheshyam had suppressed facts. He didn’t tell the Court that he had approached the Maharashtra government to consider his case. In fact, he’d rushed to the Supreme Court only when he realised that he may not get an opinion in his favour.

This brings me to the Gujarat government. In the mandamus proceedings, the Gujarat government, as respondents, had argued that Maharashtra was the appropriate government. In any case, within three months of the mandamus order, the Gujarat government released the 11 convicts. Justice Nagarathna picked up on this fact in the judgement, implying that a blameless government would have filed a review petition to bring the Court’s attention to this obvious mistake. She went so far as to say that the Gujarat government had acted in “tandem” with the convicts.

On the question of personal liberty of the convicts, the Court was unequivocal—the convicts would have to go back to prison. It did not consider the argument that the convicts had reformed. The judgement makes it clear that arguments of reformation and rehabilitation seem “hollow” when they are juxtaposed with the abuse of the rule of law.

The convicts have been directed to return to prison within two weeks of the judgement. Reportedly, some of them are now “missing.” Sounds familiar? Sometimes, the jokes write themselves.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!