Analysis

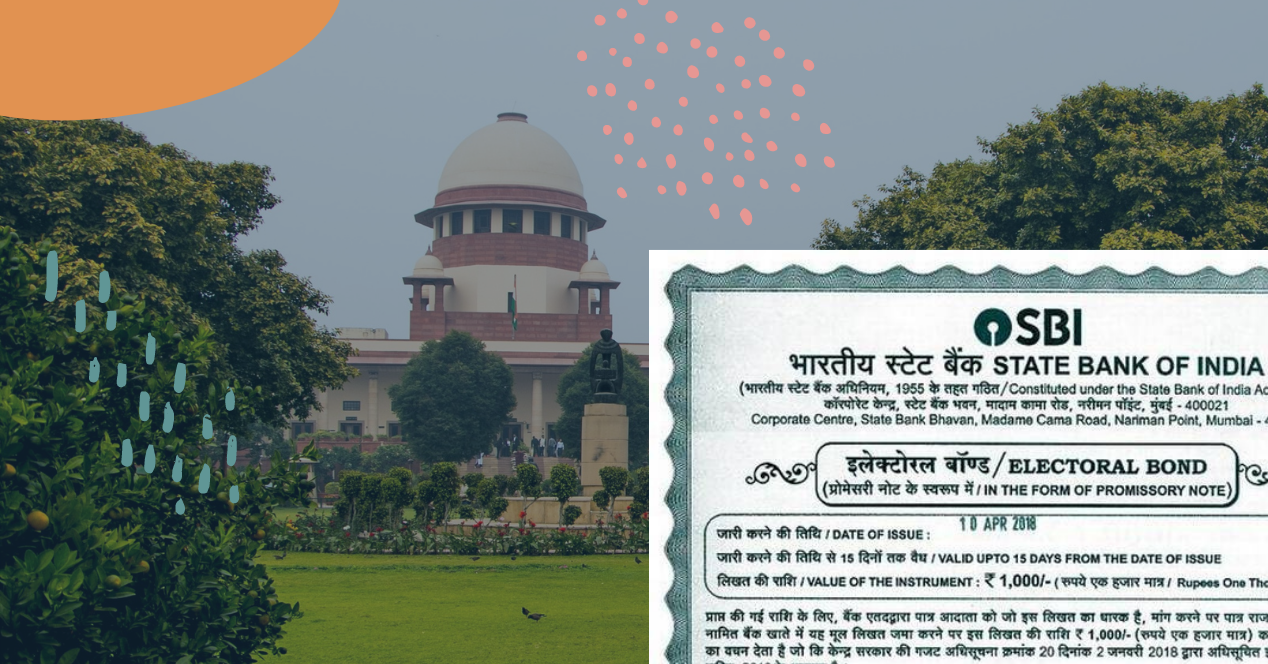

Privacy versus transparency: the electoral bonds story

DESK BRIEF: The choice between donor confidentiality and voter’s right to information will be crucial as we head towards the 2024 elections

Democracies are crumbling world over. “People still vote,” political scientists Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt write in their book How Democracies Die, “Elected autocrats maintain a veneer of democracy while eviscerating its substance. Many government efforts to subvert democracy are ‘legal,’ in the sense that they are approved by the legislature or accepted by the courts.”

Over the three days of hearings in the electoral bonds case in the Supreme Court, it felt as though I was hearing stories of two different Indias. One was the country of the responsible citizen, whose franchise has kept the flag flying in India’s representative democracy. With the anonymous funding of parties through electoral bonds, this India has lost the benefit of one of its crucial allies—information.

The other India was made of corporate entities whose work, in no small way, was inextricably tied to power and governance. For long, any support they lent to political parties had to be done in the open, allegedly exposing them to “victimisation and retribution ” from rival parties. The opportunities were many, given that the country’s election juggernaut keeps rolling on, across its 28 states and eight Union Territories.

The Electoral Bonds Scheme was introduced in 2018 as a way to “cleanse” the system of political funding in the country. The identity of the donor was designed to be confidential, known only to the State Bank of India, which is owned and controlled by the Government of India.

Petitioners argued that information on a political party’s source of funding was an “invaluable aid” for voters to ascertain where their representatives’ loyalties lay. With data suggesting that 94.25% (₹12,999 crore) of all electoral bonds purchased between March 2018 to July 2023 were by corporate entities, it was even more important for the electorate to know the source. As one counsel explained, a voter had the right to know if a party that took a stand on the Green Agenda was being funded by an oil company.

Government lawyers defended the confidentiality requirement, arguing that it was critical to eradicate black money in political funding. The Scheme guarantees the donor’s right to privacy in connection with their political affiliation. This protection from retribution, the Union explained, incentivised donors to move away from the use of cash. The overall effect, in the Union’s conception, would be a cleaner, more regulated economy.

There’s a strong precedent that privileges the right to information with respect to the candidates contesting an election. In Union of India v Association for Democratic Reforms (2002), the Supreme Court had noted that “casting of a vote by a misinformed and non-informed voter or a voter having one-sided information only is bound to affect the democracy seriously.”

The Union relied on K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India (2019), which recognised informational privacy and noted that it required a “sensitive balance between individual interests and legitimate concerns of the State.” Eradication of black money, the Union argued, was a legitimate state interest. (The Union fought tooth and nail against a right to privacy in Puttaswamy—yet another instance of the multitudes contained in democratic governance.)

Where does the balance of rights lie? When does the right to a transparent, free and fair electoral process end and the right of privacy begin? Any answer to this question will have to be in service of India’s constitutional democracy. With the 2024 general elections around the corner, all eyes are on the Constitution Bench, which could deliver a verdict that strongly influences campaign strategy and election outcome.

This article was first featured on SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!