Court Data

Pendency in the Chandrachud Court: A report card

Pendency of registered cases in the Supreme Court dropped by 3588 during Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s tenure

With a tenure of two years and two days as Chief Justice of India, former CJI D.Y. Chandrachud had an unusually long time at the helm. Only 14 of the 50 Chief Justices of India served for more than two years. With a significant amount of time on his hands, CJI Chandrachud had a chance to make a substantial and long-lasting impact. This includes the opportunity to tackle pendency, one of the biggest challenges of the top court.

While bidding farewell to his colleagues on his last working day, CJI Chandrachud announced that 5,33,000 cases were listed for hearing during his two-year stint as Chief Justice. He claimed that 1,07,000 cases were disposed of, including 21,358 bail matters. Pendency of cases, including registered and unregistered, had reduced by 11,000.

In this piece, we test his claims of having made a significant dent in the ever-increasing pile of cases.

“The raw data” and “the truth”

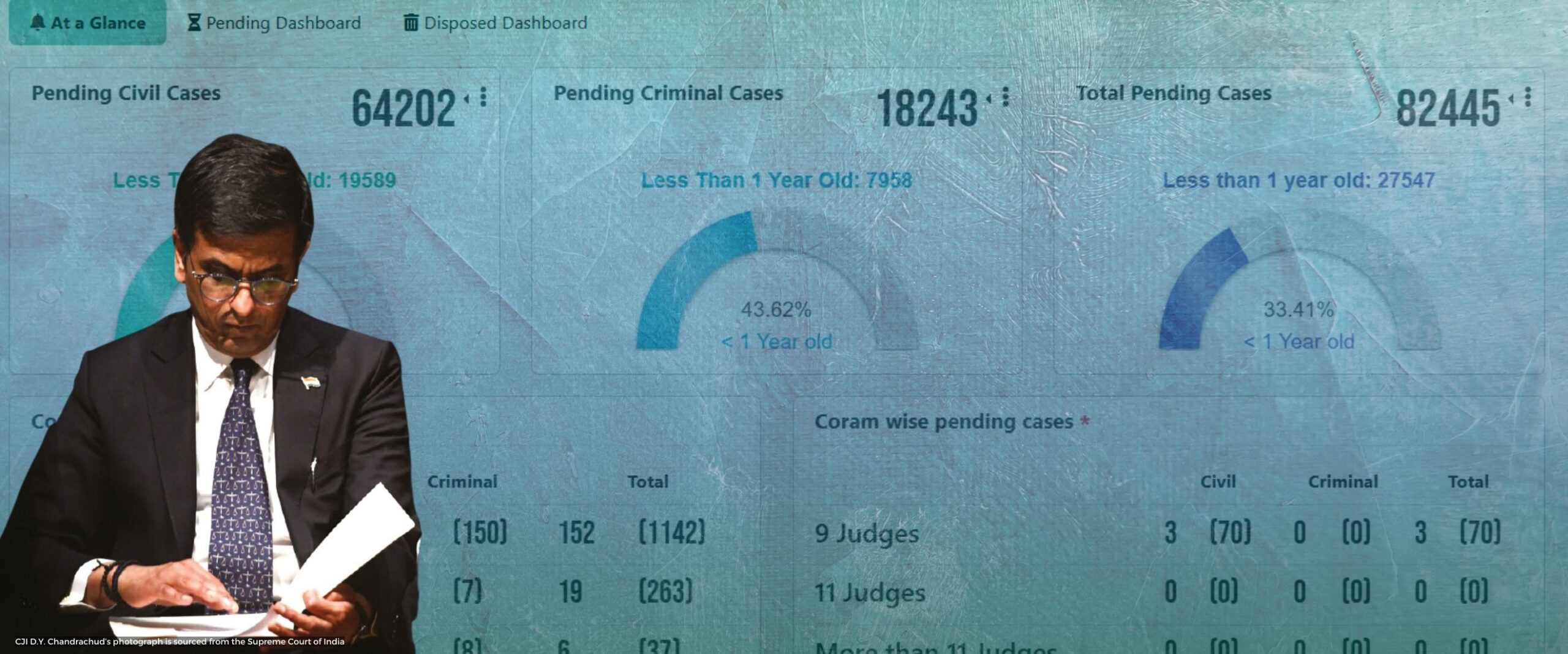

As of 10 November 2024, the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG) reported 82,445 pending cases. During his farewell speech, CJI Chandrachud sought to put those numbers in perspective. “Now you’ve probably read somewhere that the pendency of the Supreme Court has gone up to 82,000 cases. I want to tell you the raw data and what the truth of the matter is,” he said. CJI Chandrachud was referring to a change in methodology for counting pendency. Since November 2022, from the start of his tenure, the Court began to include “all diarized matters which also includes Miscellaneous Applications, Unregistered Matters, Defective matters, etc.”

This change accounts for the apparent rise in pendency numbers—from 69,598 cases in November 2022 to 78,400 in January 2023. The jump can be seen in Figure 1.

In his speech, the former Chief explained that as of 1 January 2022, pendency figures—including defective, miscellaneous and unregistered cases—stood at around 93,000. By November 2024, the number stood at around 82,000 cases. He claimed that pendency “in the course of two years [had reduced] by over 11,000 cases.”

There appears to be no publicly available official record of the complete pendency figures from 2022. However, while we wait to verify this claim against the Annual Report for this year, we’ve recorded the pendency figures at the close of every month in 2024 in our Court Data section, along with figures on the number of cases instituted and disposed of.

Despite some discrepancies in the data, it’s clear that the Court was notably productive in 2023 and 2024. As of 10 November 2024, when CJI Chandrachud officially retired, 66,193 registered cases remained pending, down from the 69,598 he inherited in November 2022.

A productive tenure

In December 2023, when we looked back at CJI D.Y. Chandrachud’s first year at the helm, the year was closing with 80,439 pending cases. This was on the back of the pandemic years (2020 to 2022), which had led to a high increase in pendency due to several patches when the Court wasn’t functioning as usual. Yet, by the end of 2023, the Court had inched closer towards clearing as many cases as were filed in the year. Compared to previous years, pendency had not jumped up by 5000 or more cases—the jump from 2022 and 2023 was a modest 1642.

In 2024 so far, pendency has increased by 2,757, from 80,221 in January to 82,978 in October. It may seem as though progress has slowed down. But this year, the Court has cleared an average of 4479 cases per month. This is more than the monthly average of 4429 for 2023, and a significant increase from the 10-month average of 2910 cases in 2022.

As disposals go, 2023 was a milestone. The Court had managed to clear 52,200 cases that year—a sharp increase from 39,800 in 2022, 24,586 in 2021 and 20,670 in 2020. While we wait to see how the year will close out, CJI Chandrachud appeared pleased with the progress the Court had made under his leadership.

The efforts made in the Chandrachud Court to tackle pendency have been systematic and deliberate. He leveraged technology as his “steadfast ally” to improve access, processing of cases, disposal rates and recording mechanisms.

He overhauled the mentioning system, requiring lawyers to submit requests for case hearings via the digital route, instead of gathering before a bench every morning and seeking permission to be heard. Under CJI Chandrachud, counsel had to submit a letter outlining the urgent matter to the Registry in advance.

The Court also constituted Special Benches to reduce the pendency of Regular Hearing matters, specifically for matters related to death penalty, crime, motor accident claims, tribunals, land acquisition, compensation, direct and indirect tax and arbitration. It also set up Special Benches to tackle certain three-judge bench matters. In the 2023 Annual Report, the Court claimed that approximately 166 Special Bench sittings were held that year.

The Court’s approach to clearing Constitution Bench cases was also commendable. When CJI Chandrachud assumed office, there were 32 such cases pending. By the end of his tenure as Chief, he had constituted 16 Constitution Benches, variously consisting five-, seven-, and nine-judges. Hearings were conducted and judgements delivered in all of these cases. On the last day of his tenure, the NJDG showed 28 pending Constitution Bench cases.

Further, CJI Chandrachud initiated a week-long Special Lok Adalat in mid-2024, disposing of 925 cases from a list of 4,884.

Then why does the pendency issue persist?

In his farewell speech before members of the Bar and other judges of the Supreme Court, the former Chief expressed gratitude and pride as he noted that institution of cases had nearly doubled since 2020. There were 54,000 cases filed in 2023, compared to about 29,000 in 2020. Based on data available until November this year, he calculated that about 60,000 cases had been filed in 2024. “Look at the kind of support which the Bar has given us by the number of cases you have filed, that shows the sense of faith which you and the public have in us,” he said.

But back in November 2022, while hearing a petition seeking an increase in the number of judges in the Supreme Court, CJI Chandrachud had said that the issue was not about the strength of the Bench; it was about “widened access” to a point where the Court was “becoming dysfunctional.” Despite the marked increase in disposals, overall pendency rose by 3648 cases during his stint as CJI. Perhaps the former Chief had correctly identified the issue of “widened access” in his first month in office.

Looking ahead

The focus now shifts to his successor, CJI Sanjiv Khanna. In a single-page statement released by the Court as he took office, CJI Khanna said that his “priority” would be “making judgments comprehensible to the citizens and promoting mediation.” The statement also said that he has a vision to “make courts approachable and user-friendly.”

In the run-up to the start of his tenure, The Times of India reported that it had “gathered” during “a couple of interactions” with Justice Khanna that pendency would be his “primary focus”. (The one-page statement released by the Court does mention “the need to tackle case backlogs” as a “challenge”.)

In his first week at the top court, CJI Khanna issued a circular suspending regular hearings until further notice. This means that the Court will use Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays—which are typically reserved for hearing arguments in cases—to hear ‘after-notice miscellaneous matters’ (cases which the Court has issued notice in but not yet admitted for hearing). We asked advocates what they thought about this move and wrote about it here. While some worry that this will lead to a further rise in pendency, others see it as a viable approach for the short term. Given his six months, Justice Khanna may not have long to create a dent in pendency numbers.