Analysis

“National political parties haven’t appointed information officers despite being subject to RTI law”: Anjali Bhardwaj, Amrita Johri

In a wide-ranging interview, the transparency activists also spoke about how the Electoral Bond Scheme compromises the right to information

Anjali Bhardwaj is a transparency activist, social worker and founder of Satark Nagrik Sangathan (SNS). She is also the co-convenor of the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information. Amrita Johri works with SNS and NCPRI.

SNS, set up in 2003, is a civil society organisation that uses the Right to Information law to obtain information on constitutional and government functionaries, and works with poor and marginalised communities in Delhi to improve accountability on rations, health, sanitation, pension and other necessities.

Earlier this month, in the SNS office in Delhi’s Malviya Nagar, Supreme Court Observer spoke to Bhardwaj and Johri about their work in uncovering the details about the Electoral Bond Scheme. We also touched upon broader issues relating to voter rights and the application of the right to information regime on political parties.

Bhardwaj and Johri have filed a petition seeking timely and transparent appointments of information commissioners under the RTI Act before the Supreme Court. Bhardwaj is also a member of Common Cause, one of the petitioners in the electoral bonds case.

The transcript has been edited for clarity.

When the Electoral Bond Scheme was first introduced, you were among the first transparency activists that filed RTIs asking for the record of the deliberations to be made public. What motivated you to seek out this information?

Bhardwaj: Several people filed RTI applications seeking details about the Electoral Bond Scheme. Commodore Lokesh Batra (former Navy officer and transparency activist) and I were among them.

It’s been a long-standing demand that there should be greater transparency in the funding of political parties. And it’s been widely recognised that the fountainhead of corruption in many ways is political party funding.

It is important for a voter to know where political parties get their funding from. When entities, especially large corporations and industrial houses are funding political parties, it’s very often for a quid pro quo.

Individual MPs are not so important in our scheme of things anymore as much as our political parties, due to the Tenth Schedule. Given all of this background, it’s very important that people know who is funding political parties, so they have an understanding of who those parties are likely to work for once they’re voted into power.

In fact, in 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata Party came to power, one of the things that it committed to was greater transparency, greater accountability. They also said that they will bring in more transparency in political party funding. So when the Electoral Bond Scheme was brought in, naturally the expectation was that it would lead to a better outcome in terms of transparency.

What was really required—which is what we thought would happen—is the government saying that no amount of donation to any political party will be anonymous.

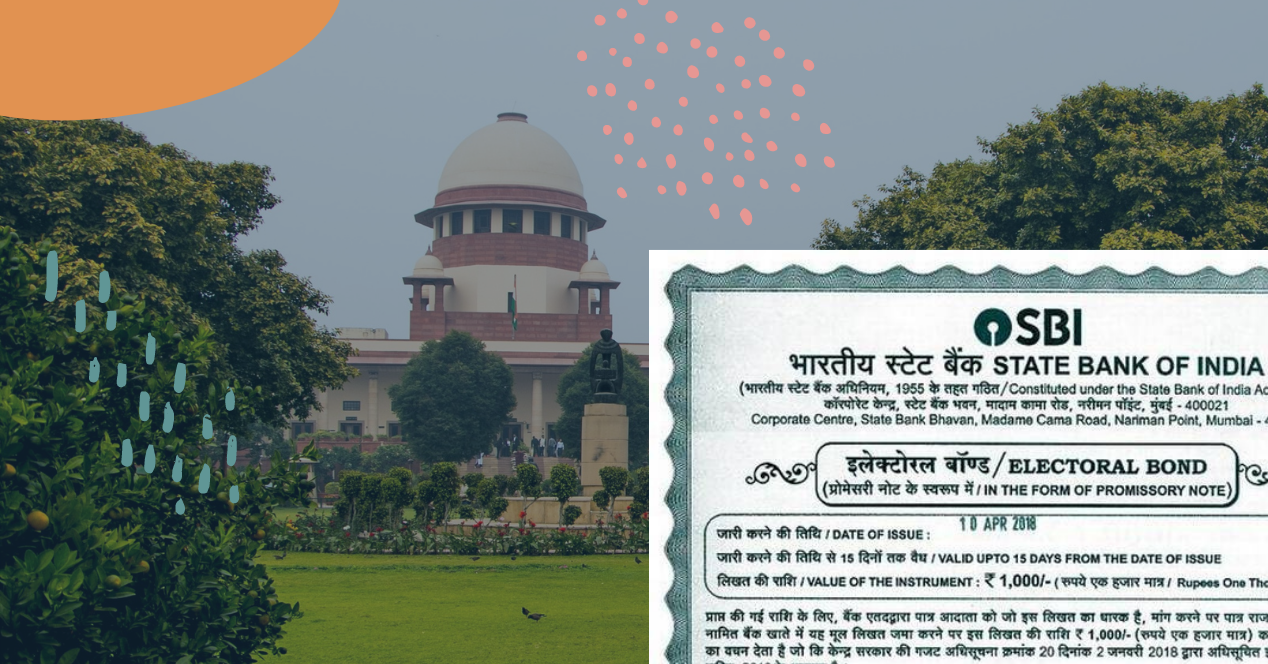

Instead, what the scheme has done is that political parties can receive any amount of donations through electoral bonds and no one, including oversight institutions like the Election Commission of India, will know the source of this funding.

Amendments were made to four laws to pave the way for the Electoral Bond Scheme—Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, Representation of the People Act, 1951, Income Tax Act and Companies Act—increasing opaqueness and consolidating the role of big money in electoral politics.

Electoral bonds have opened the floodgates to unlimited anonymous donations to political parties. In conjunction with amendments to other laws, they allow anonymous financing by Indian as well as foreign companies. The only positive of the scheme is that bonds can only be bought through banking channels. But since these are bearer bonds, there is no way to know whether the entity which bought the bond is the one giving it to the party or if it exchanged hands for some consideration.

In today’s context, we are talking about a system where increasingly there is a push to go digital and even the poorest vendor on the street is encouraged to have a digital system of collecting money. So it was not unimaginable that political parties could have been asked not to accept any cash and push for complete transparency in their funding.

The argument for allowing anonymous donations made at the time of introducing the scheme as well as in Court was that it would protect the confidentiality of the donor. The scheme was designed to insulate donors from retribution from the political parties that they did not donate to. How has the scheme fared in delivering this promise?

Bhardwaj: So the political party itself is not supposed to know who’s giving them the bonds and who’s contributing to them. They are not expected to tell any independent body who they’re getting the money from, because they’re not meant to know. Now, in practice, we know that these things don’t quite work this way. If somebody wants to give money to a political party, especially if it’s a large sum of money which may have a quid pro quo element to it, donors will find a way to tell political parties.

The issuing authority is the State Bank of India, which is a public sector bank. And even in court, when the bench questioned, they said that if it is required, SBI can trace who the electoral bond was bought by, and which political party received it.

Johri: During the hearing, the government had explained that the identities of those who purchased electoral bonds could be traced if required by a court order or by a law enforcement agency. Once that possibility exists, we know how the system typically works—with the SBI and law enforcement agencies under the ruling party’s control, it would not be unimaginable that pressure is mounted to ascertain identities.

Let’s take anonymity at face value and agree that providing confidentiality is the legitimate aim. Even then, why was this scheme needed? The instrument of electoral trusts already provided that layer of anonymity because if a company didn’t want its name to show up, it could donate to a trust. Then that trust makes a donation to a party. So it’s not that there was no other system. In fact, on electoral trusts itself, there was much criticism that you’re not allowing people to know who is actually donating to which political party.

Bhardwaj: If one distils the problems, the key issue is that it fundamentally undermines people’s right to know. The courts have held again and again that, in a democracy, citizens have a fundamental right to information flowing from Article 19(1)(a).

The government is claiming that electoral bonds reduce cash donations. But if you look at the amendments, the option to take cash donations, and that too anonymously, still persists. It’s a well-known secret that parties would break down large cash donations and show them as less than ₹ 20,000 to exploit a loophole which allowed donations below that threshold to remain anonymous. This loophole continues to exist, only the threshold has been reduced—which just requires additional creative accounting!

You’ve been instrumental in bringing information on the legislative deliberations and responses of independent institutions out on this. Did you find that there was some resistance to the sharing of this information? What sort of prompts are required to get the right kind of data?

Bhardwaj: What we’ve always understood and advised is that an RTI response is only as good as the question that you’re able to frame and ask. But I have to say that though it did take some time for the information to come, there wasn’t that much resistance in sharing the data.

Johri: There were just two points on which information was sought. One was “provide the reference number of all files in which the Electoral Bond Scheme 2018 was processed and approved by the cabinet.” The second was “provide a copy of all files (including all notings, correspondence, records, which are part of the file) in which the Electoral Bond Scheme 2018 was processed and approved by the cabinet.” In response, they gave the full bunch of deliberations and details of the scheme.

It was sometime in March of 2019 that we filed the RTI and by May, the information came to us. It was interesting that there was no resistance since public authorities often drag their feet on issues like this.

Bhardwaj: I would say that electoral bonds has been one of the public interest issues which really benefited from the use of the RTI Act, in terms of bringing out information on how the deliberations happened, where, and at what stage everything was done. Maybe now it would not be so easy to get that information.

Johri: Perhaps the way RTI has been used to bring out information on important issues like this is why there have been attempts to weaken it.

Bhardwaj: Also, because it has all been used and cited in the case. When the government blatantly brings in laws and claims one thing and then the papers show something else, it becomes very embarrassing.

In this case, the government said that we are doing this to have greater transparency—that is what the finance minister said on the floor of the house. They claimed to be doing this to get rid of black money and cash. The papers show us that the RBI Governor, in a letter, warned the government that there will be no way to ensure that there won’t be middle men or aggregators, flagging the high risk of money laundering, forgery and counterfeiting.

The information accessed showed that RBI, ECI and the Legislative Department raised several concerns. Some of the objections raised by the RBI were rejected by the government claiming, among other things, that these came late “at a time when the Finance Bill is already printed.”

It is becoming increasingly difficult, in any case, to access information under the RTI. Now the data protection law has amended the RTI Act to expand the scope of the exemptions under Section (8)(1)(j). This means that any information that relates to personal information will not be provided.

Once the Digital Personal Data Protection Act becomes operational, even if the Supreme Court were to strike down the aspect of anonymity in electoral bonds, it will not be easy to access names of donors. They’re likely to say that this is personal information and disclosing it through RTI will violate the DPDP Act.

We are at a time today where there is a huge pushback on a citizen’s right to know. In this wider context, the Electoral Bond Scheme is very much an attack on the right to information.

In January 2023 Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice P.S. Narasimha de-tagged the cases on this, and one of the three cases that it was split into was the petition to bring political parties within the ambit of the RTI Act. Where does that case stand in all of this?

Bhardwaj: There were attempts made to file RTI applications to political parties and the political parties said that we don’t come under the RTI law. The matter went up to the Central Information Commission. The commission, in 2013, ruled that six national political parties are all public authorities.

But since then, political parties have been sitting in what we often call “uncivil disobedience” because they’re just not complying with the order of the Central Information Commission. There is no court ruling that has stayed the order of the CIC. And yet no political party has actually appointed Public Information Officers to give information to people. We hope the SC takes up this case soon.

One could argue that political parties must not come under the ambit of the RTI Act because they hold sensitive, dangerous information that must be protected. Parties often have confidential discussions and plans to tackle or oppose government policies. Parties even see this as a way to weaken a party, opening them to attacks from competitors. In the Electoral Bonds case, the Attorney General argued that “there can be no general right to know anything and everything without being subjected to reasonable restrictions” and that the “right to know for the general health of democracy will be too over-broad.”

Bhardwaj: The way the RTI stands today, there is no way that political parties can argue that they don’t fall under the ambit of the Act. If they fall under the ambit of the RTI Act, then there is no way they can argue that they will not give information that they have on finances, on candidates’ selection and other issues.

There is in-built protection within the framework of the RTI Act to exempt certain categories of information—any disclosure by parties would be subject to these clauses. Also, surely a political party does not hold information which is more sensitive than that held by the government or the judiciary or the legislature.

Parties are performing a public role, you are collecting public funds and there is a certain importance attached to you in a democracy. You are also being given taxpayers’ money, so you have to be answerable to people. A political party is as free as any other public authority to use exemptions under the RTI Act and refuse access to information.

How do you think the lack of information on sources of funding through electoral bonds has impacted people?

Bhardwaj: Voters are certainly less informed than before. And so it really becomes a question of how the ostensible benefits of electoral bonds weigh out against voters being deprived of their right to know, and how critical in a democracy we think that is.

Johri: If we forget the technical question of do we know less or more, I think it has created suspicion in the mind of the public. This scheme certainly reduces public trust. And I think that you have to judge government actions from a prism of public trust.

Bhardwaj: At the very least, I should know that there are robust regulators that are able to make sure nothing is going wrong anywhere. But if the regulator is also saying that they don’t have access to this information, then what is left? All of this is very much about citizens feeling that their vote counts. Who I’m electing to run my government should actually be working for me as a citizen and not for a corporate interest or an industry simply because that’s where they are getting money from.