Analysis

Mostly quiet in foggy Srinagar

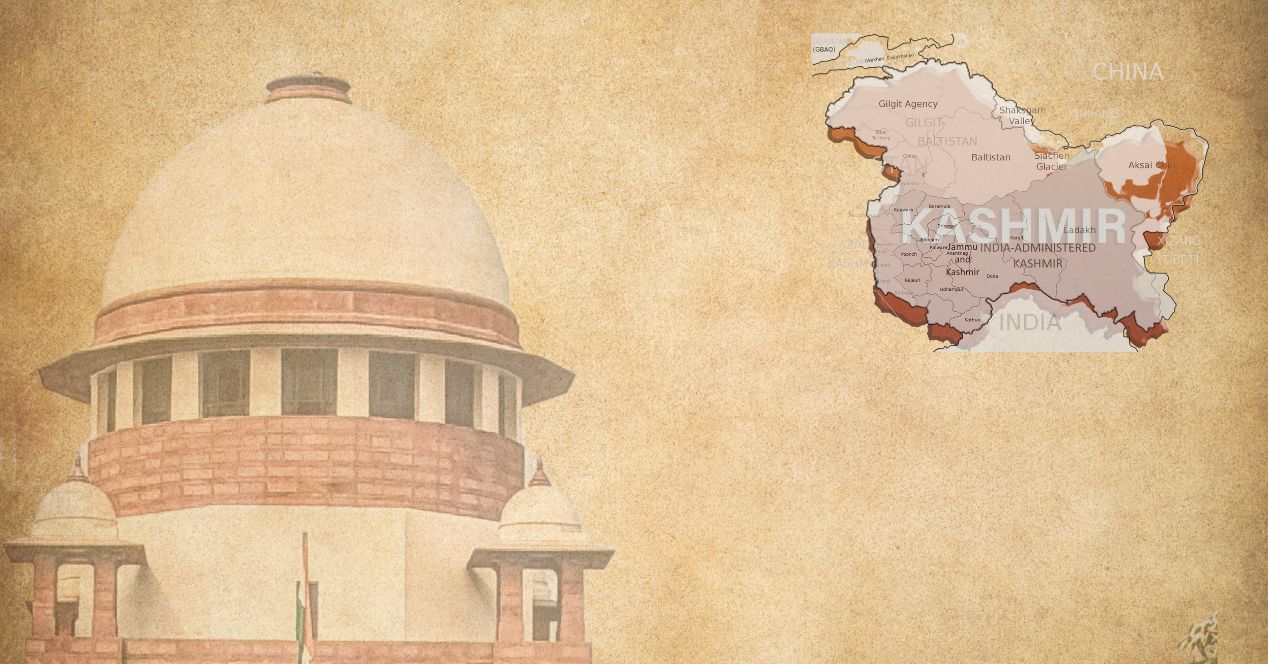

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s upholding of the abrogation of Article 370, detachment and disappointment hang over the capital of J&K

Srinagar: It was long thought to be a momentous day but when it came, there was no sign of the frisson that has marked out days of this nature. On Monday, the day the Supreme Court held the abrogation of Article 370 as constitutional, the people of Srinagar went about their business as usual. The judgement came on a cold December morning while fog still enveloped the Valley. The fog over the fate of Jammu and Kashmir in India’s federal scheme had finally lifted, but there seemed to be a sense of detachment and indifference among the general population.

Announcements and statements

If one looked closely, however, there were signs that the Union government had been cautious about the fallout. Ahead of the verdict, police had ordered the tightening of security arrangements in Kashmir. Additional security personnel had been deployed on the ground and checkpoints had been set up. Reportedly, social media activity was also being monitored.

The politicians were quick to express their disappointment, but from behind closed doors. They alleged they were under house arrest. Omar Abdullah of the National Conference and Mehbooba Mufti of the Peoples Democratic Party—both former chief ministers—recorded video messages from their own homes and posted them on their social media accounts. Abdullah panned the camera to a chain on the green-coloured front gate of his residence and said that he had been locked in by the authorities. Manoj Sinha, Lieutenant Governor of J&K, and the police said that the claims of house arrest were baseless.

While the politics played out on social media, Kashmiris went about a day that looked—on the surface, at least—like an average winter one. There were no shades of the tension, apprehension and roiling anger of the days in the aftermath of the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. Then, as now, the two former chief ministers had been detained. But that detention—which lasted months—was far more consequential. The freedom of movement of common Kashmiris was severely restricted in the days following the abrogation. The communication blackout that accompanied the announcement grew into the longest internet ban in the country’s history.

Meanwhile, earlier this week, celebrations in the Central Government’s Delhi camp have been effusive. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party was exuberant, having essentially drawn the line under a promise in their election manifesto. Prime Minister Narendra Modi penned a gushing article on the issue that was carried by several newspapers the next day, including several prominent English and Urdu outlets in Kashmir.

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta released a statement that suggested that he was involved in the “entire process” of planning and defending the abrogation. “It is only the iron will of our Hon’ble Prime Minister Shri Narendra Modiji and resolute decisiveness and brilliant strategy of our Hon’ble Home Minister Shri Amit Shahji which made this historical decision possible,” he said, “The nation will ever remain indebted to them.” (The five judges who presided over the case were described by Mehta as “legendary” and “undisputable intellectual giants.”)

Lawyers point out contradictions

In Kashmir, expectedly, the politicians’ messages didn’t wade into the technicalities of the judgement and were mainly directed towards their supporters, who were asked to keep their chin up and fight on. But a couple of Kashmiri lawyers Supreme Court Observer spoke to were baffled by some of the reasoning adopted by the Court.

Senior Advocate Zaffar Shah, who represented the Bar Association of the J&K High Court in the matter, told SCO that the judgement raised more questions than answers. The only part of the judgement that went in favour of the petitioners was the holding that Paragraph 2 of Constitutional Order 272 was ultra vires. This paragraph had replaced the words “Constituent Assembly” with “Legislative Assembly” in Article 370(3). Since J&K was under President’s Rule at the time, Parliament took on the functions of the Legislative Assembly and “recommended” the abrogation, as required by the Article.

Ultimately though, it looked like the Union government needn’t have gone through with these legal gymnastics: the Court held that the power of the President to abrogate Article 370 was plenary and that the Constituent Assembly’s recommendation wasn’t binding.

“Since the replacement of ‘Constituent Assembly’ with ‘Legislative Assembly’ was expressly held by the Court to be ultra vires, the legal consequence would be that ‘Constituent Assembly’ would continue to remain in Article 370(3),” said Shah, “After having declared it to be ultra vires, its consequences are denied. This view to us appears to be unsustainable, in view of both textual as well as contextual understanding and evaluation of the constitutional position.”

The Court also didn’t go into the question of the bifurcation of the state into two Union Territories. The grounds it provided for this was that the Solicitor General had orally assured the Court that statehood would be restored in the future. “We feel that the Court ought to have expressed its opinion on the validity of reorganisation,” Shah said, “The relationship has been unilaterally determined by the President of India or the Union government, without the concurrence of the representatives of the state, when the action under challenge directly affected the state. It is against constitutional morality, constitutional values and democracy.”

Advocate G.N. Shaheen, a former general secretary of the Bar Association of the J&K High Court, called the verdict a “riyasati judgement”—a judgement for the rulers, and not for the people. He echoed Shah in pointing out the legal contradictions within the judgement. “The judgement has the character to change the Constitution from a federal structure to a unitary structure,” he warned, “This process is not only adverse to the people of J&K, but it is against all of India, as cries are now emerging.” As for what it means for Kashmir going forward, Shaheen said: “Now, we are united in silence.”

Sanjay Kak, a Kashmiri filmmaker and author based in Delhi, compared the present silence with the one that enveloped the Valley in the wake of the revocation in August 2019. “What keeps people silent now, and prevents them from even discussing the judgement are forces that are much more invisible, and perhaps more malign,” he said, “The Srinagar media has reported the judgement blandly, with no significant commentary, discussion, reactions, nothing.”

In any case, Kak said, whatever rights Article 370 protected were more symbolic than real, having been consistently eroded over the last 70 years. “They existed more in the way of a fig leaf, and were important to what I called the ‘unionist’ parties and their support base. For many other people, it had already been hollowed out and lost meaning. One barometer of what people are really thinking about all that’s going on will emerge if an assembly election is called. Maybe that is why elections remain long overdue in J&K.”

Silence in the city

Across Srinagar city, however, several people that SCO spoke to feigned ignorance about the verdict, which is unusual for a place always interested in news, rumours and political developments. Many of them outright refused to speak about the issue.

A tea-shop owner in Lal Chowk, not wishing to be identified, expressed resignation before muttering “good riddance” in a defeatist tone. Several younger people I spoke to in the city claimed to be unaware of the issue. A group of college students, who asked to be anonymous for fear of reprisal, said that the decision had not surprised them at all.

Their refusal to be identified bore out what Shaheen, the lawyer, had told me. “People are resisting voicing their opinion for fear of reprisal from the state,” he said, “Editorials by intellectuals have been published in the Indian media, but not a single paper here has dared to talk about it.” The judgement has been reported widely in Kashmir-based media outlets, but, as Kak also pointed out, scathing or supportive commentary on the judgement has been lacking in these publications. (This may not be entirely out of step with the ordinary course—in the last few years, editorials in Kashmiri print media have typically focussed on issues other than politics.)

Shaheen also pointed to an advisory that had been issued by the police ahead of the verdict. The advisory urged people to not propagate “false narratives” or post “provocative content” on social media.

Lack of expectation was a sentiment that seemed to be shared by many across the city. “It is their court so the judgement couldn’t have undone what they did,” an auto driver from the Khanyar area told SCO, “When any government comes, they stock institutions with their officers, so why should we have expected anything from the court in this case?”

Numan Zargar, a recent law graduate, said that he had diligently followed the arguments in the matter. “I was hopeful because the Supreme Court is a leveller,” he said, “In that sense, I was looking forward to the judgement and hoping that the Court will uphold constitutional principles.” But he was left disappointed by what he felt was a recusal of the judges from their constitutional duties. “As a Kashmiri, it is a letdown. What happened in 2019 was a constitutional fraud that was played on us.”

However, Zargar said that the struggle will go on—it may take decades, he said, but the injustice will be undone. “I have hope but I also have disappointment.”

Adil Rashid is a Srinagar-based independent journalist. He has written for FiftyTwo, The Caravan, The Guardian, PARI, among other publications. Previously, he worked at Outlook.

Cover image: Photo by Zeeshan Ali on Unsplash. Modified by SCO.