Court Data

More than 65 percent pending Supreme Court cases stuck at admission stage

90% of filed cases are disposed after admission hearings, raising questions about whether the Court can be selective about what it hears

In the Supreme Court, Wednesdays and Thursdays are designated as regular hearing days, when benches hear matters that often require prolonged hearings and extensive arguments. Mondays and Fridays are “miscellaneous days.” On these days, the Court hears fresh admission matters—cases that have not yet been admitted for regular hearings. On these days, counsel attempt to persuade Division Benches to admit their cases and schedule them for regular hearing days.

Tuesday is reserved for hearing after-notice miscellaneous matters: these are instances where a notice has been issued to a party in a fresh admission matter but the case has still not been admitted for regular hearing.

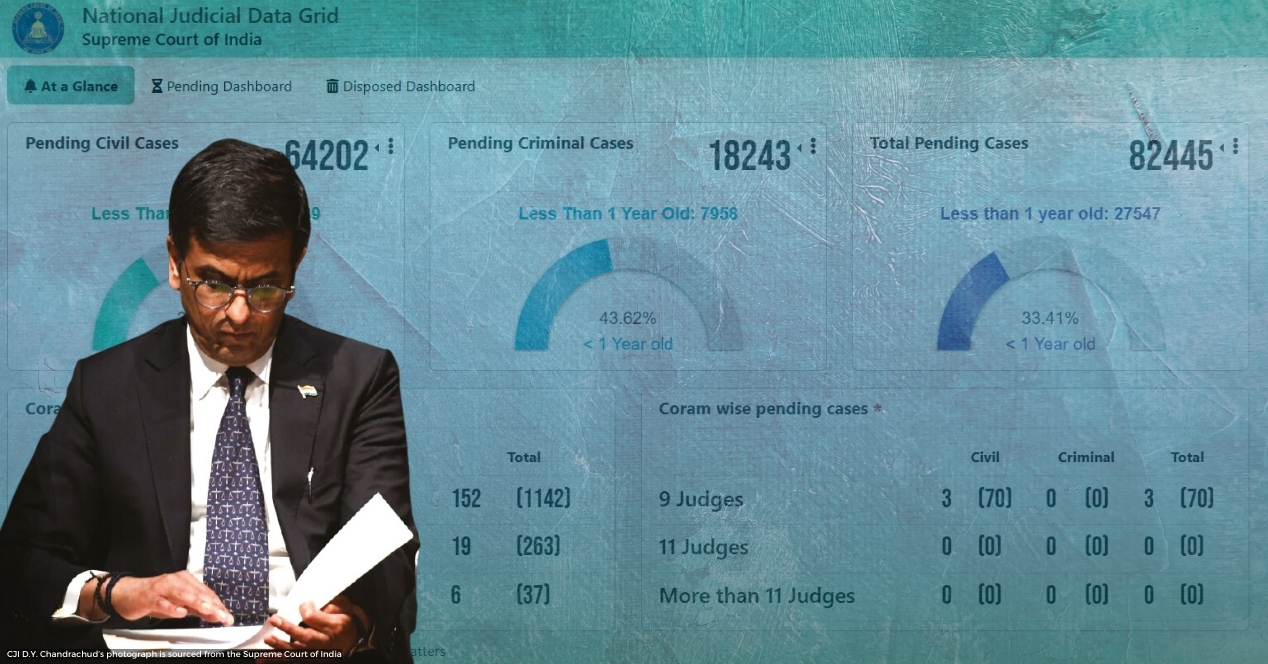

According to the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG), as of 24 February 2025, the Supreme Court has 81,274 pending cases. Out of these, 17,022 cases are “unregistered cases”. Among the 64,252 “registered cases”, 65.2 per cent are matters currently at the admission stage while the remaining are regular matters. This suggests that admission matters occupy the lion’s share of the docket. A bulk of these are Special Leave Petitions (SLPs)—that is, appeals against High Court decisions. About 90 percent of the cases that the Court disposed of in 2023 and 2024 were disposed at the admission stage.

In his first week in-charge, CJI Sanjiv Khanna shifted focus in order to clear the backlog of admission matters. He temporarily halted the listing of regular matters on Wednesdays and Thursdays, earmarking these days exclusively for the hearing of miscellaneous cases throughout the second half of November and December 2024. Regular hearings only resumed when the Court returned from its winter break in January 2025.

The Supreme Court’s Annual Report reveals that 72.22 percent of pending cases in 2024 were admission matters (the Annual Report does not have data for the last four months of the year). CJI Khanna’s decision could be seen as an effort to streamline the docket by accelerating the clearance of admission cases.

Studies have shown that there are significant time lags between a matter being instituted and it being taken up for an admission hearing. Legal scholar Nick Robinson’s chapter in A Qualified Hope observes that “a typical case takes on average about two years to be heard as an admission matter and approximately another two to be decided as a regular hearing matter.” This observation was published in 2019, when pendency was under the 60,000 mark.

It is unclear whether CJI Khanna’s strategy has significantly reduced the backlog. The Supreme Court Observer has filed a Right to Information request seeking data on the number of cases disposed of during the November-December 2024 period. Meanwhile, in this article, we look at historical data to illustrate how the inordinate time the Court spends on hearing admission matters is affecting the disposal rate of regular matters.

Cases instituted since 2020

Figure 1 illustrates three split bars detailing the number of cases instituted (or filed) since 2020 and up to August 2024. The yellow bar indicates the total number of cases instituted in the year, the red bar separates the admission matters from the total and the green bar represents the number of cases that progressed for regular hearings.

In 2020, 7 percent of cases progressed to regular hearing. In 2021, that figure was only 5.8 percent. 2022 saw an increase up to 18 percent cases, followed by a dip in 2023 (7.6 percent) and a rise again in 2024 (11.6 percent).

On average, then, over the five-year period, only 10 percent of matters instituted in the Court proceeded to the regular hearing stage.

Cases disposed of since 2020

Figure 2 shows the number of disposals in the last five years. The yellow bar indicates the total disposals whereas the number of matters disposed of at the admission stage and the number of matters disposed of after regular hearings are indicated in red and green respectively.

In 2020, 86 percent of cases were disposed of at the admission stage. The rate of disposal didn’t fluctuate much in the following years: 2021 (89.5%), 2022 (87%), and 2023 (87%).

In 2024, 94 percent of total cases were disposed of at the admission stage.

The “see-saw” resulting in mounting pendency

To see how the break-up between admission stage matters and regular matters interplays with pendency, let’s look at the data for the last three years (2022-2024) in Figures 1 and 2.

In 2022, over 34,000 matters were disposed of at the admission stage. This was more than the matters instituted and in the admission stage that year (30,000). However, the pendency of regular matters increased by over 600 cases. In 2023, disposal of regular matters crossed 6000 cases. However, this focus on regular matters coincided with a drop in the disposal of matters at the admission stage. The Court disposed of 45,000 admission matters but more than 50,000 fresh matters were in the admission stage that year.

2024 saw a similar trend as 2022. While disposals of admission matters exceeded their institution by 230-odd cases, the disposal of regular matters dropped to 2253 (until August). Unsurprisingly, the total disposals did not exceed the total institutions that year.

From the data, we perceive a “see-saw” between admission and regular matters—when the disposal rate of one category rises, the other tends to decline. Therefore, pendency has increased regardless.

If we calculate the congestion rate—the ratio of total pending cases to the total number of disposals in the previous year (up to August 2024), assuming no new cases are filed—it would take the Court over two years to clear its backlog.

Can the Court be more selective about what it hears?

Interestingly, the admission stage itself often becomes a prolonged process. Litigants frequently seek out high-profile lawyers who can persuade the bench to admit a case, leading to lengthy arguments that can stretch for hours. Ideally, the Court functions for five and a half hours daily, and on miscellaneous days (Mondays and Fridays), 50 to 70 matters are listed in each of the 15 to 17 courtrooms. On productive days, courts manage to admit or dispose of a significant portion of these matters.

However, even on regular hearing days, some after-notice admission matters are often listed before scheduled hearings commence. During a typical regular hearing day, a courtroom may only handle three to four matters within five hours, as counsels can take two to three hours to argue each case.

A disposal rate of 90 percent at the admission stage leads one to wonder if the Court is perhaps too welcoming to SLPs. The problem can be traced to the way the Court’s Registry is organised. The Registrar of the Court does not have the power to reject or opine on a file. It can only advise for a petition to be refiled if it spots any technical defects that have nothing to do with the merits of a case.

Contrast this approach with the Supreme Court of the United States, which has a mechanism for law clerks to assess petitions on merit and recommend to the justices which cases can proceed to oral arguments. The opinion of the clerks assists the justices in determining—privately—whether the case should be taken up or not. Admittedly, SCOTUS receives far fewer petitions than the Indian Supreme Court. But the metric that matters in the present discussion is the number of cases that a Supreme Court hears oral arguments for. For instance, the SCOTUS hears oral arguments in only about 80 of the 7000 to 8000 petitions it receives on an average each year.

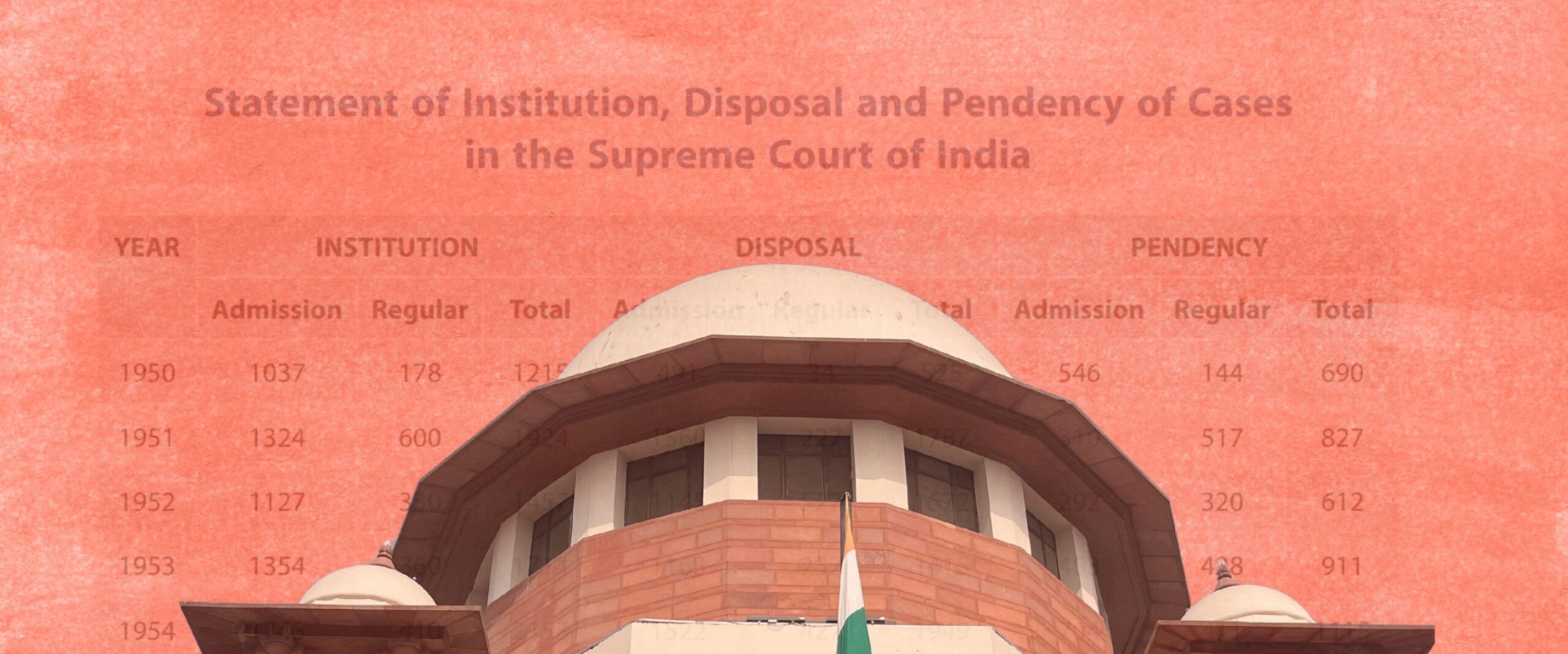

Lack of archival data

A major challenge in analysing pendency is the lack of consistent data on admission and regular matters each month. The Court’s Annual Report provides figures but the data set is often incomplete. For instance, most of the Supreme Court’s Annual Reports of the last few years have not carried data for the last quarter of the financial year.

Previously, the Court’s publication Court News offered detailed breakdowns, but no new editions have been released since 2019. The Supreme Court Chronicle, the Court’s monthly newsletter, also omits these statistics. Currently, the only available resource for a month-wise breakdown is the National Judicial Data Grid (NJDG), which maintains a live count of cases. However, it offers no mechanism to retrospectively cull out data for a specific month. While the NJDG allows filtering by year, monthly data remains elusive. Readers who know of alternative sources providing this breakdown are encouraged to share them.