Analysis

Mighty broad shoulders

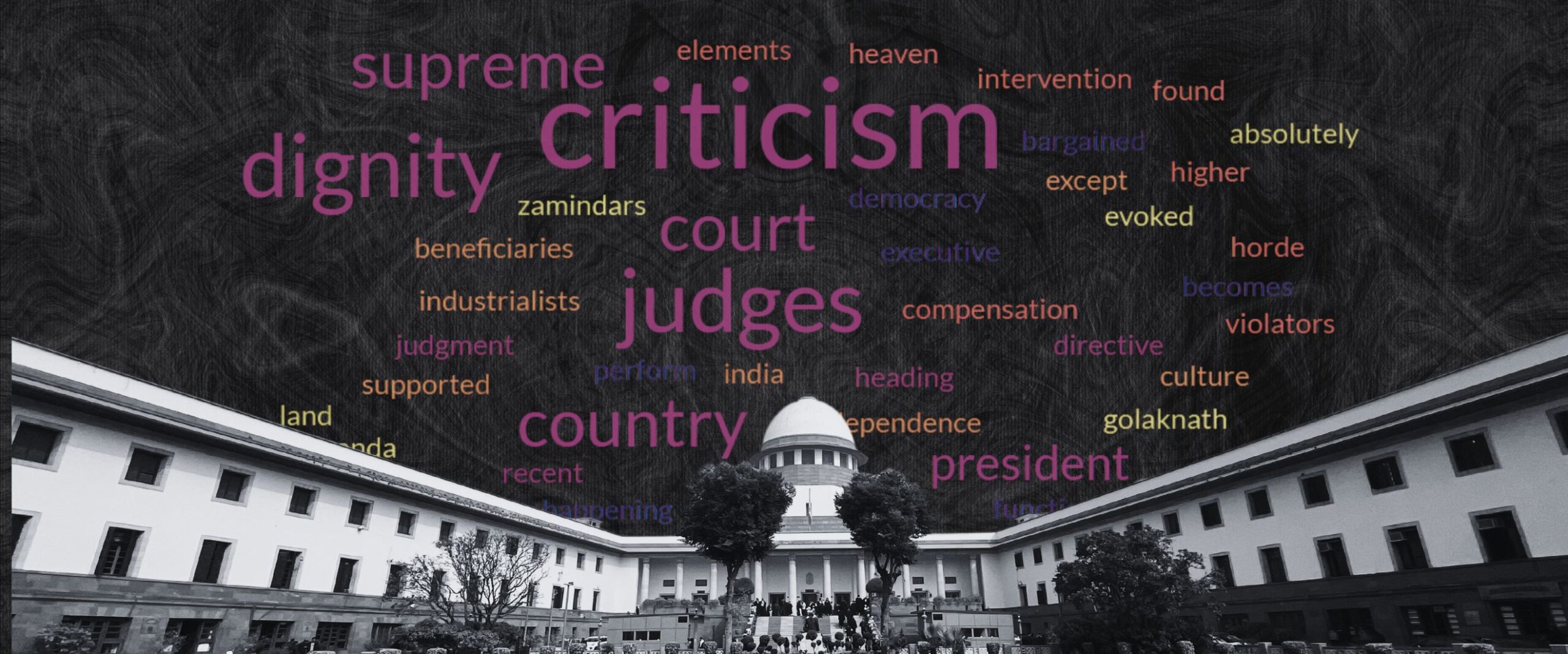

The Supreme Court has reason and precedent to shrug off recent criticism from executive functionaries and maintain its ‘dignified bearing’

“We have judges who will legislate, who will perform executive functions, who will act as a super-Parliament, and absolutely have no accountability because the law of the land does not apply to them,” Jagdeep Dhankhar, Vice President of India, said at an event on 17 April. His comments were made in the context of the Supreme Court’s Judgement in State of Tamil Nadu v Governor of Tamil Nadu. In its decision, the Court had granted deemed assent to state legislature Bills that Governor R.N. Ravi had withheld for a long time.

The Court had also prescribed timelines for the Governor and the President to opine on and grant assent to Bills. All this was done under its wide power “for doing complete justice” under Article 142. “We cannot have a situation where the Supreme Court directs the President of India,” Dhankar said. “Article 142 has become a nuclear missile against democratic forces, available to the judiciary 24×7.”

Two days later, Nishikant Dubey, a Member of Parliament from the BJP, also criticised the TN Governor Judgement while claiming that the Court wants “to take this country towards anarchy.” He then went after CJI Sanjiv Khanna for agreeing to hear the series of petitions challenging the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, saying that the Chief was promoting a religious divide and was “responsible for all the civil wars happening in this country.”

Soon after, advocates asked the Court to initiate contempt proceedings against Dhankar and Dubey for attacking and lowering the “dignity and authority” of the Court.

The Supreme Court’s power to punish for contempt arises from Article 129 of the Constitution. The Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, further clarifies instances where the Court may exercise this power. It defines criminal contempt as any speech that “scandalises the authority of the court” or interferes with the “due course of judicial proceedings” and the “administration of justice.” In addition to confirming the Court’s suo moto power, the Act also allows individuals to file for contempt after receiving approval from the Attorney General or Solicitor General.

One of the Supreme Court’s earliest contempt cases dealt with a similar issue—a political figure making “derogatory” remarks against it. In 1967, Kerala Chief Minister E.M.S Namboodiripad had called the judiciary “an instrument of oppression” and said that judges were “dominated by class hatred, class interests, class prejudices.” In the contempt proceedings, Namboodiripad argued that he meant no disrespect—he was simply following the ideologies of Marx, Engels and Lenin.

The Court tested the correctness of that claim by breaking into a long exposition of Marxist ideology. They concluded that “in all (their) writings there is no direct attack on the judiciary selected as the target of people’s wrath.” They charged Namboodiripad with contempt, stating that he “misunderstood” communist philosophy and that his comments were clearly meant to cause “dissatisfaction with, and distrust of all judicial decisions.”

Two decades on, P. Shiv Shankar, then Union Law Minister, suggested that judges were ‘black-robed elite’ who supported “zamindars”, “bank magnates”, “industrialists”, “antisocial elements”, “bride burners” and “reactionaries”.

While noting that the “times and clime have changed” since the Namboodiripad decision, the Bench acknowledged that the “erosion of faith in the dignity of the court” had happened not because of comments like the ones made by Shiv Shankar but by its “inability” to “deliver quick and substantial justice to the needy.” Though the speech was harsh, the Court found that it was more suitably characterised as an opinion, a historical review, a fair criticism and an entry point to study the class composition of the Court’s judges.

Judges often state that the institution’s shoulders are broad enough to withstand criticism. About Dhankar’s comments, Justice Surya Kant reportedly commented: “We are not worried… the institution comes under attack every day.”

The Court will likely hear Dubey’s case next week. At the time of writing this article, the AG has not yet provided consent for a case against Dhankar. If either of these matters take substantial form, we may see how the Court’s approach to trenchant criticism from the executive has evolved in the decades since P. Shiv Shankar (1988).

One sentence from that Judgement might serve as a beacon: “A guideline for the Judges to observe is not to be hypersensitive even where distortions and criticisms overstep the limits, but to deflate vulgar denunciation by dignified bearing.”