Analysis

Justice Khanna’s era begins

As the incoming Chief Justice, Sanjiv Khanna has the enviable task of balancing continuity with fresh reforms

Justice Sanjiv Khanna will assume office as India’s 51st Chief Justice on 11 November 2024. He will head the Supreme Court as Chief for six months before his retirement on 13 May 2025. His is the second shortest tenure—after Justice B.V. Nagarathna’s scheduled 36-day run in 2027—among the eight next chief justices.

The Khanna Court will have to deal with a high pendency of over 82,000 cases. (When CJI D.Y. Chandrachud assumed office, the pendency stood at over 69,000 cases). These include Constitution Bench cases on critical issues like the constitutionality of sedition, the role of a Speaker in disqualification proceedings and the Sabarimala review. Other important cases in the Court’s docket include challenges to the marital rape exception, the process of appointing members to the Election Commission and the validity of the Bihar caste census.

From his predecessor CJI Chandrachud, who retires on 10 November, Justice Khanna will inherit a technologically revamped Court, which has in place e-filing systems, an online pass system for access to the Court, and more recently, livestreams of all courtroom proceedings.

As Chief Justice, Justice Khanna will also head the Supreme Court Collegium to recommend elevations to the Supreme Court and the High Courts. During his tenure, the Collegium led by him will likely elevate four new judges to the Supreme Court.

Before he takes the helm, we explore his life and career, notable judgements and what’s in store.

From Shershah Road to Tilak Marg

Born on 14 May 1960, Justice Khanna hails from a family of lawyers. His uncle, Hans Raj Khanna was a former judge of the Supreme Court. His father Dev Raj Khanna was a judge in the Delhi High Court. Justice Khanna graduated with an LLB degree from Delhi University in 1983.

He practised at the Delhi High Court for almost 23 years before being elevated as an Additional Judge in 2005. In February 2006, he was made a Permanent Judge.

On 10 January 2019, the Supreme Court Collegium led by then Chief Justice Rajan Gogoi recommended Justice Khanna for elevation to the Supreme Court along with Justice Dinesh Maheshwari. At the time, Justice Khanna ranked 33 in the combined seniority list of High Court judges and Justice Maheshwari ranked 21. The resolution noted that Justices Khanna and Maheshwari were “more deserving and suitable in all respects than other Chief Justices and senior puisne Judges of High Courts, for being appointed as Judges of the Supreme Court of India.”

Justice Khanna’s recommendation sparked some debate. Reportedly, Justice S.K. Kaul of the Supreme Court (now retired) had written to CJI Gogoi objecting to Justice Khanna’s elevation. Kailash Gambhir, former Chief Justice of the Delhi High Court, also wrote to the President stating that elevating Khanna to the Supreme Court by ignoring 32 other senior judges was “appalling and outrageous”. However, President Ram Nath Kovind appointed Justice Khanna as a Supreme Court judge and he assumed office on 18 January 2019.

On 17 October 2024, CJI Chandrachud wrote to the Union recommending Justice Khanna as the next Chief Justice of India. The Union notified his appointment on 24 October.

Notable judgements in the Supreme Court

In his close to six-year tenure in the top court, Justice Khanna has been a part of over 450 benches and authored over 115 judgements. He has been part of benches that have delivered important judgements on matters of electoral independence, bail and personal liberty, arbitration and the Court’s discretionary powers.

Earlier this year, a Division Bench led by him rejected a plea for 100 percent VVPAT verification of votes, reasoning that the existing Electronic Voting Machine system ensured quick and error-free counting.

In July, a bench of Justices Khanna and Dipankar Datta granted bail to then Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal from his arrest by the Enforcement Directorate, noting that he had “suffered incarceration for over 90 days.” The bench also referred a crucial legal question to a larger bench: whether “additional grounds” should be read into the pre-existing criteria for arrest under Section 19 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002.

Justice Khanna has also sat on several Constitution Benches. He was part of the seven-judge benches which upheld the validity of an unstamped arbitration agreement, rejected the Union’s plea to increase the compensation for victims of the 1984 Bhopal Gas Tragedy and upheld the Bar Council’s power to conduct the All-India Bar Exam.

In his first year in the Supreme Court, he authored the majority opinion for a five-judge bench in what is popularly known as the ‘RTI Judgement’. The bench was dealing with the question of whether subjecting the office of the Chief Justice to the Right to Information Act would breach the independence of the judiciary. Justice Khanna held that judicial independence doesn’t necessarily oppose the right to information and that RTI requests should be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Last year, he authored the unanimous opinion on behalf of a five-judge bench which held that the Supreme Court could use its discriminatory powers under Article 142 to directly grant divorce on the ground of irretrievable breakdown of marriage—a ‘no-fault’ ground not recognised under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. He also authored a concurring opinion in the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the abrogation of Article 370, which granted special status to the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Earlier this year, he authored a concurring opinion as part of a five-judge bench which struck down the Union’s Electoral Bond Scheme as unconstitutional, emphasising that donors’ right to privacy doesn’t apply when donations are made through banking channels.

Important cases before the Khanna Court

One of the first things Justice Khanna is expected to deal with are the pleas challenging the marital rape exception in Indian criminal law. CJI Chandrachud’s bench had heard the matter for one day on 17 October but ultimately decided to defer hearings as counsel needed more time to argue. It will be up to CJI Khanna to constitute a fresh bench to hear this case.

The Khanna Court is also expected to continue hearing the suo moto case on the rape and murder of a woman trainee doctor at Kolkata’s R.G. Kar Medical College. The National Task Force established by the Chandrachud Court is expected to submit its pan-India protocol for the security of doctors soon. CJI Chandrachud had promised that the Court would pass enforcement orders in the matter—it remains to be seen if the Khanna Court follows through on that promise.

Justice Khanna is also likely to constitute benches to hear other important cases like the constitutionality of the Election Commission Appointments Act, 2023, the validity of the Bihar Case Census, the scope of the “need and necessity” of arrest in PMLA cases and other cases that were listed but never heard during the Chandrachud tenure, such as challenges to the restitution of conjugal rights and the criminalisation of triple talaq.

There are several Constitution Bench cases from which Justice Khanna will have to start from scratch—by constituting benches to hear them. These include the case to decide if a Speaker against whom disqualification proceedings have been initiated can start disqualification proceedings against other members of the House, the constitutionality of sedition law in India, the review of the Court’s Sabarimala decision and the constitutionality of Muslim marriage laws.

The Khanna-led Collegium

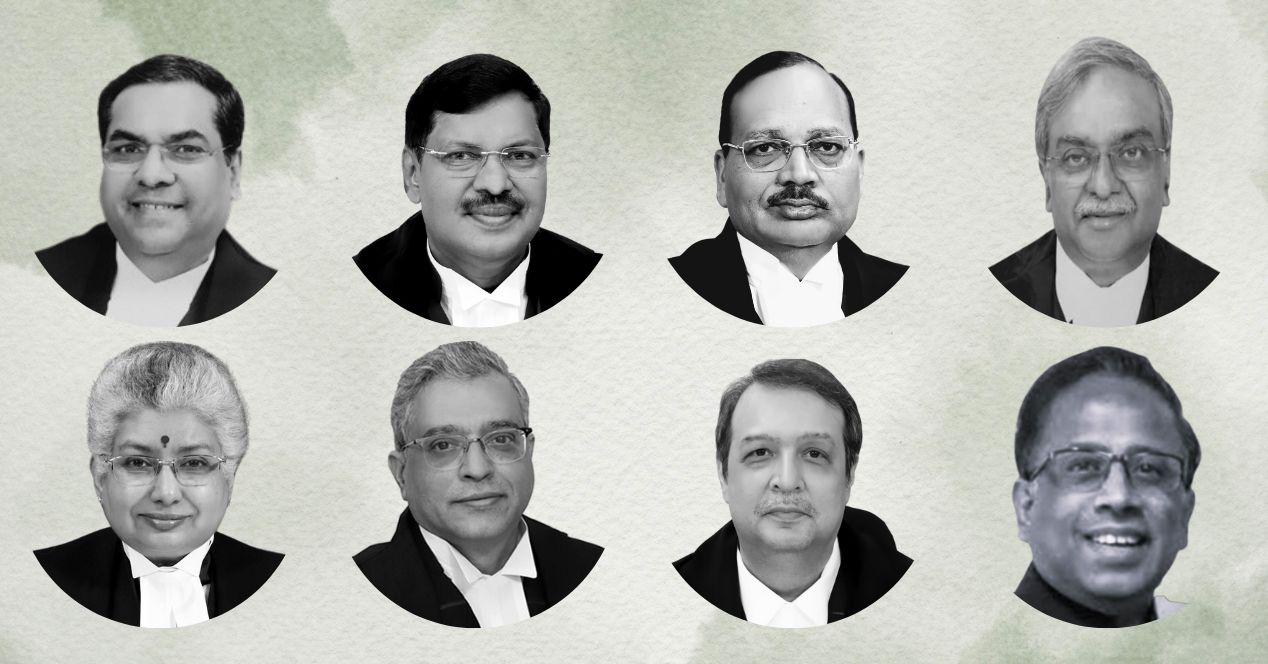

The Supreme Court Collegium comprises the Chief and four senior-most judges of the Court. Once CJI Khanna assumes office, the Collegium will comprise him and Justices B.R. Gavai, Surya Kant, Hrishikesh Roy and A.S. Oka. With Justice Roy’s retirement on 31 January 2025, Justice Vikram Nath will join the Khanna-led Collegium.

The Khanna-led Collegium is immediately tasked with nominating two new judges to the Supreme Court to fill in the vacancies created by the retirements of Justice Hima Kohli and CJI Chandrachud. In January next year, the top court will see two retirements—Justices Roy and C.T. Ravikumar. So the Khanna-led Collegium will have to recommend two more judges to fill in these vacancies. It will be interesting to see whether the new Collegium will address the lack of gender diversity at the top court.

Appointment to the Supreme Court aside, the Khanna-led Collegium will also have to address the high number of vacancies in High Courts across the country. As of 1 October 2024, High Courts have a combined sanctioned strength of 1114 judges (including permanent and additional judges). Of these, 363 positions (32 percent) remain unfilled.

Lingering institutional questions

As CJI, Justice Khanna will also become the Master of Roster, responsible for constituting benches and allotting cases. The rostering system has often been criticised for lack of transparency and arbitrariness. In fact, an assessment of Constitution Bench allocation during the tenures of former CJI U.U. Lalit and incumbent CJI D.Y. Chandrachud shows that while Justice Lalit has followed a ‘Seniority Pools’ method, a discernible pattern did not emerge under Justice Chandrachud. CJI Khanna has the opportunity to put the uncertainty to rest and create a publicly defensible allocation rationale—either by returning to Justice Lalit’s ‘Seniority Pools’ method or coming up with his own balanced formula.

There are other process- and operations-related issues that could also do with some addressing. For instance, members of the bar have raised concerns about the inordinate delays caused in the process of listing cases by the Supreme Court’s Registry. Then, there is the pendency problem—even as the Supreme Court has for the most part maintained a healthy disposal rate during CJI Chandrachud’s tenure, over 82,000 cases remain on its docket.

One could argue that six months is too short a tenure to address institutional issues which have accumulated over decades. After all, even CJI Chandrachud’s two-year tenure, the longest for a CJI since 2012, was not enough. But a relatively short tenure has not come in the way of previous chief justices ringing in big changes. Justice Lalit, who was in charge only for two-and-a-half months, resurrected Constitution Bench activity by listing 25 long-pending cases.

As the incoming Chief Justice, Justice Khanna stands on the cusp of great challenges and opportunities. The onus is on him to carry forward the good work of the Chandrachud Court and redress some of its shortcomings. Beyond what he inherits, he has the institutional canvas to leave a mark in his 180-odd days in the Chief’s seat. It’s safe to say that India’s 51st Chief Justice has his work cut out.