Analysis

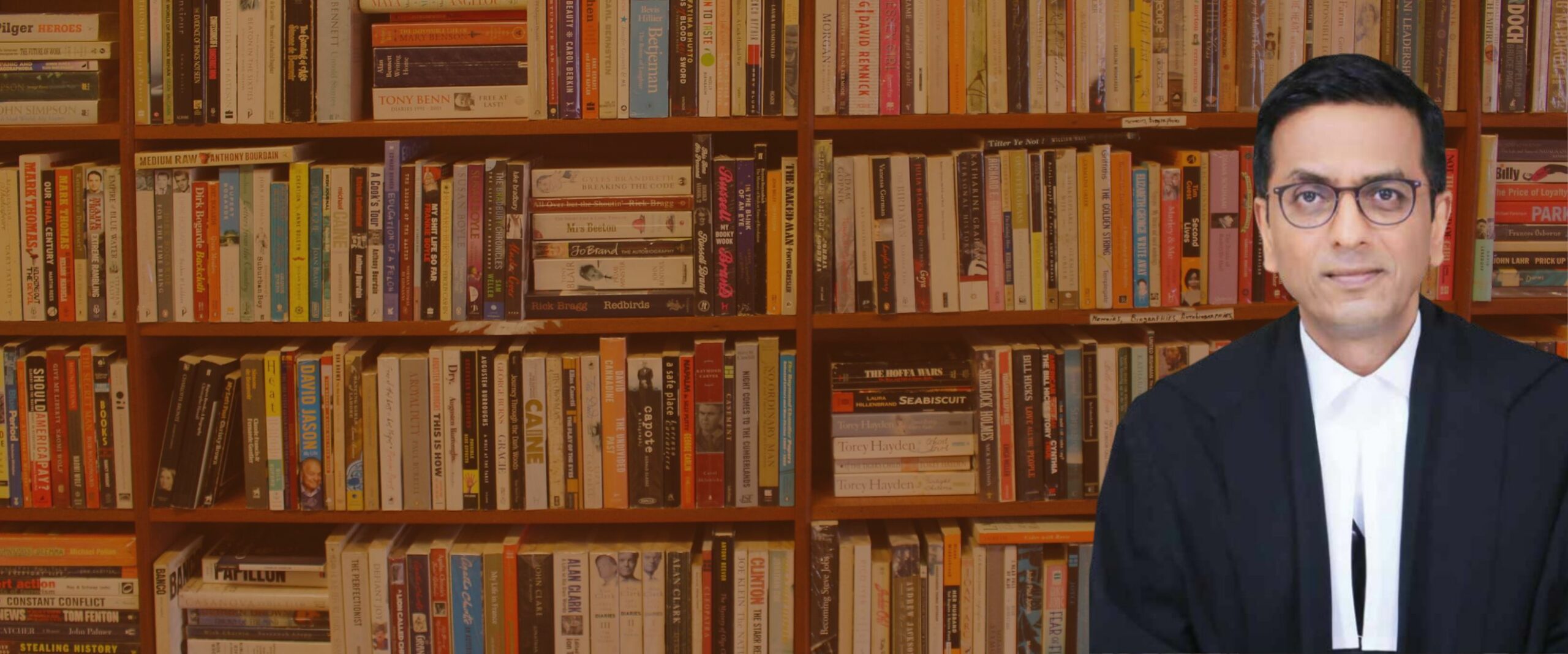

Justice Chandrachud’s Approach to Judging

Justice Chandrachud regularly explores academic and popular sources and seeks to set aside ‘formal’ legal traditions.

When news about Justice D.Y. Chandrachud being the next Chief Justice of India broke, a good part of Twitter appeared thrilled. They saw the oncoming of the era of a judge who could ‘overturn’ a Beatles lyric ‘All you need is love, love; Love is all you need’, to ‘so we need a little more than love. Structural changes, as well as attitudinal changes, are essential’. Others were less optimistic about his ability to bring this change during his tenure as CJI. Strong opinions about Justice Chandrachud’s style of Judging seem to be commonplace, so what exactly does he bring to the table?

Justice Chandrachud has created a legacy of Judgments that are crafted through deep research, which are often not limited by legal precedent. His Judgments are not confined by purely legal reasoning, as they often draw upon external academic, literary, and pop-culture resources.

While most of his celebrated decisions were written during his tenure as a Supreme Court Judge, his expansive approach to writing Judgments can be seen in play even during his career as a High Court Judge.

The ‘Former’ Chief Justice Chandrachud

In 2015, Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice Narayan Shukla of the Allahabad High Court heard a peculiar case. Advocate Ashok Pandey had filed a petition, asking the Court to hold that Judges should no longer be referred to as ‘Justices’. That term, in his view, was reserved by the Constitution for a Chief ‘Justice’. Others were ‘Judges’ of a Court.

Unsurprisingly, the Bench dismissed the case. They said that the Chief Justice was considered the ‘first among equals’. Chief Justices perform the same duties as any other Judge of that Court, with the only difference being additional administrative functions, such as allocating cases to different combinations of Judges. The Bench said two terms can be used interchangeably and there is no express bar against using the term ‘Justice’ in the Constitution. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud wrote the Judgment. He wrote: In order to consider the merits of the submission, it would be worthwhile to explore the history of the expression ‘justice’.

Justice D.Y. Chandrachud then launched into a deep analysis of the etymology of the word ‘justice’. He traced the Latin roots of the word and its later English adaptations in the 13th century, when it was first used as a title for a Judge. Then, he referred to conventional and law dictionaries to show that a Judge is one who renders justice, and established that the two terms are irrevocably linked.

That there is no express bar against the use, and that a Chief Justice is not superior may have been sufficient reasoning. However, Justice Chandrachud regularly couches his decisions in an academic exploration of the issues in a case. He dives deep into history, literature, and academic and non-academic writing as he examines the issues before him.

When he was appointed to the SC in 2016, he brought this distinct style of writing Judgments with him. For instance, In Navtej Singh Johar (2018), where the SC decriminalised same-sex relationships, Justice Chandrachud analysed the colonial origins of its criminalisation. He spoke about how it was ‘firmly rooted’ in Judeo-Christian morality and covered the increased prosecution of homosexual people in England following World War II. Historical deep dives however, are not all that Justice Chandrachud brought to the SC’s table.

Academic Approach to Judgment Writing

Justice Chandrachud, who will assume the office of the Chief Justice of India on November 9th, 2022, is an alumni of both the Faculty of Law at Delhi University and Harvard Law School. His interests extended to teaching as well—he was a visiting professor at the University of Bombay teaching Comparative Constitutional Law between 1988 and 1997 while he was still a practising lawyer.

His wide experience and interest in academic and non-academic literature regularly seep into his Judgments. In Navtej Singh Johar (2018), Justice Chandrachud routinely quoted the works of Irish poet and playwright Oscar Wilde, who was arrested in 1895 for having same-sex relations.

In his sole dissenting opinion in the Aadhaar Review (2018) case, he refers to the theories of American legal philosopher Lon. L. Fuller. He animatedly mentioned his reference to Fuller in his address during a conference in 2018. ‘I wrote about Fuller recently in one of my Judgments. I’m not sure how relevant it was but I had to get it into that Judgment by referring to the Polycentric Web’.

His scholarly inclinations in his decisions seem to stem from a personal belief that Judges should not entirely be bound by the Judgments that precede them. In his address during the conference, he mentioned an analogy by American legal philosopher Ronald Dworkin, who compared the process of writing a Judgment to writing a new chapter in a novel. The author must follow the existing ‘plotline’ (or legal precedent), giving them less scope for discretion. However, Justice Chandrachud has advocated for Judges to find ways to break free from these restrictions.

The Need to Set Aside Formal Legal Traditions

In the same conference, Justice Chandrachud emphasised the role of a Judge’s creativity to ‘distinguish’ their decisions from past cases. In order to do this, he says Judges must use their ‘…human ability to do what is right and perhaps cast away a previous decision which you think is perhaps not acceptable’.

As a part of a 9-Judge Bench in Puttuswamy (2017), Justice Chandrachud overruled the Constitution Bench decision in ADM Jabalpur (1976). The Court in 1976 held that the right to personal liberty could be suspended when an Emergency is declared. Justice Chandrachud held that this verdict, which included his father Justice Y.V. Chandrachud in the majority, was ‘seriously flawed’, steering the Court away from the much-maligned and strict interpretation of the Constitution.

Justice Chandrachud regularly expresses his disinclination towards a traditional and formal approach to Judgment writing in his public addresses. Speaking to the students of National Law University, Delhi (NLUD) in October 2022, he said ‘As I conclude, my hope is that you refrain from perpetuating the traditional formalistic approaches to law. Instead, you should strive to adopt a legal approach that puts at its center the quotidian lives of people, who struggle on a daily basis to make their ends meet and take care of their family. That is the true redemption of justice.’

During the IDIA National Conference 2018 he spoke about what it means when law students are told to ‘think like a lawyer’. He said that the law essentially ‘reduce(s) the human element in the law…in terms of these (legal) constructs which basically mask the essential nature of human relationships…which is not as impersonal as the law would make it out to be’.

After the address concluded, an audience member asked Justice Chandrachud about whether the Supreme Court was waiting for a petition for the legalisation of same-sex marriage following the Judgment in Navtej. He said the Court must deal with these issues and problems on a case-by-case basis and ‘...in answering those problems you obviously lay the groundwork for a much broader recognition for the future. I think that is the craftsmanship of a Judge, of not overreaching the actual problem you are deciding but yet laying the groundwork for a much broader recognition of rights’.

(With edits and inputs from Gauri Kashyap, Associate Managing Editor)