Analysis

‘Judgement Thursday’ strikes again

Last week’s decision upholding Section 6A of the Citizenship Act marks the beginning of a series of rulings expected in the coming days

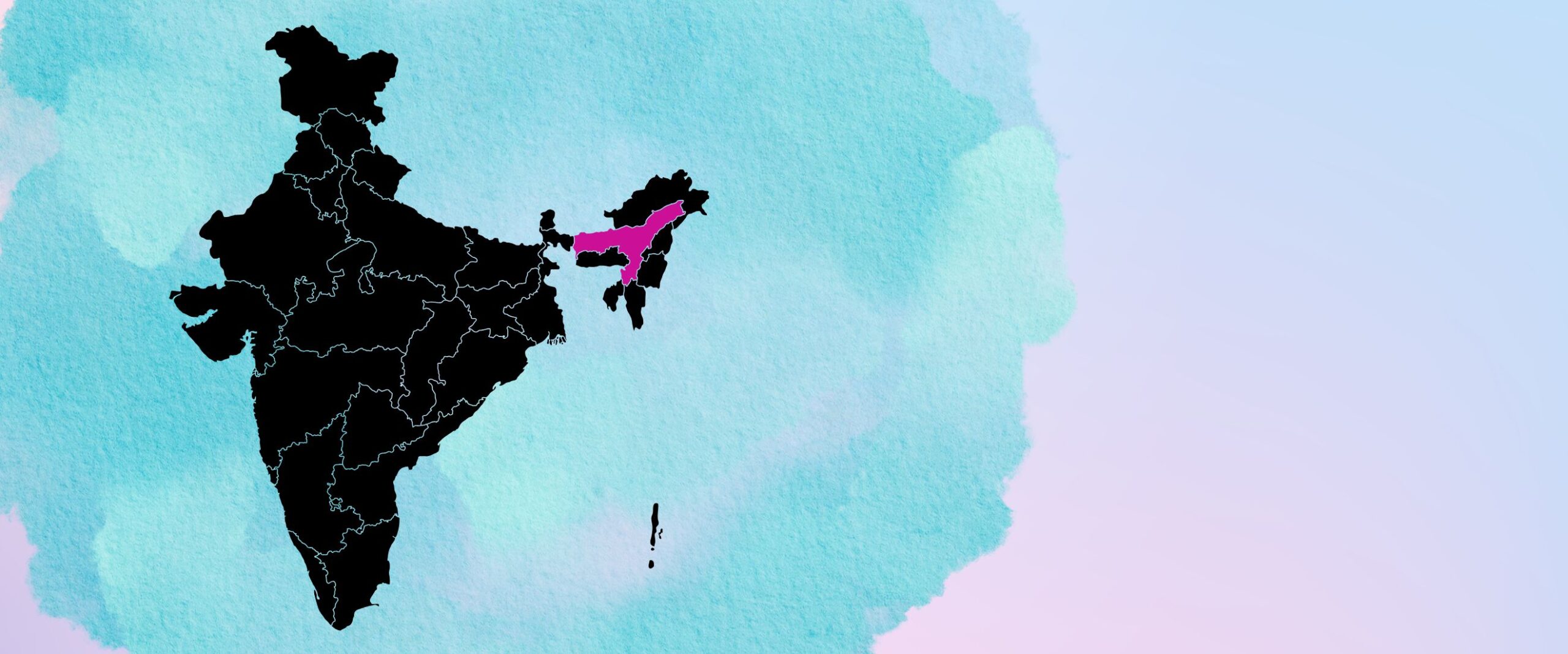

On Thursday, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court, in a 4:1 majority, upheld the constitutionality of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955. The implication of the judgement is that the cut-off date for granting citizenship to those who entered Assam from East Pakistan after India’s independence is 1 January 1966 and not 1951, as was seemingly preferred by the government of Assam. (Consequently, the Bharatiya Janata Party at the centre and a section of the party in Assam have had different reactions to the judgement.)

Section 6A was inserted in 1985 as a result of the Assam Accord. The agreement between student unions protesting the influx of immigrants and Rajiv Gandhi’s Congress government was the culmination of a turbulent period in the state’s history. Section 6A was a legislative compromise that created two categories—one for those who entered Assam before 1 January 1966 and another for those who entered between 1 January 1966 and 24 March 1971, the day before the Pakistani Army initiated a military crackdown to suppress the Bengali nationalist movement. Both categories were given citizenship, with the second category being denied voting rights for 10 years from the date of their detection as a ‘foreigner’.

Why was there a need for a new cut-off date when citizenship had already been provided to migrants during the Partition? CJI Chandrachud’s concurring opinion explains this. Article 6 of the Constitution provides that any one who migrated to India on or after 19 July 1948 would be deemed a citizen on the date of the Constitution’s commencement so long as they were able to prove six months of residence preceding the date of their registration application as a citizen. However, many migrants entered India after 26 July 1949, which was the last date to enter the country and satisfy the six-month residency requirement of Article 6. CJI Chandrachud said that Section 6A was designed to accommodate those migrants.

The petitioners’ contentions ranged from violation of their cultural rights to the duty of the Union to intervene to settle the ‘internal disturbance’ the immigration had caused. The Court dismissed them, asserting that arguments for cultural exclusivity undermined the principle of fraternity enshrined in the Constitution. One argument, however, resonated with the bench—the issue of weak implementation of Section 6A. The majority opinion authored by Justice Surya Kant ordered a court-monitored implementation of Section 6A, aimed at identifying and expelling migrants who entered after the March 1971 cut-off.

Justice J.B. Pardiwala based his dissent on this issue. He pointed to the failings of Section 6A(3), which granted citizenship to migrants from the 1966-71 period but barred them from voting for 10 years. This provision, he wrote, was designed to address concerns around the electoral impact of recent migrants. Observing that the government hadn’t identified those who entered during that period in a timely manner, he recommended the prospective striking down of Section 6A(3). The effect of this would be that citizenship granted prior to the judgement would remain unaffected but those who have not yet been identified as citizens would be treated as illegal.

It’s no surprise that the judgement came on a Thursday. The previous two Constitution Bench verdicts—on the state’s power to tax mines and minerals and the validity of sub-classification—had been pronounced on a Thursday. In advance of CJI Chandrachud’s retirement on 10 November, the clock has been ticking louder. On Wednesday nights over the last two-and-a-half-months, my colleagues and I have opened the causelist with a special sense of anticipation (unpacking a new judgement!) and anxiety (extra hectic days at work!). Many Thursdays before this week passed without judgement.

Now, there are six judgements pending and two working Thursdays before the Chief hangs his boots. We’re anticipating a flurry of decisions and imagining the newsroom descending into the frenzied chaos of an episode of The Bear. Sailors often speak of a storm when their joints begin to ache. We’re aching with anticipation here at the Supreme Court Observer. A storm is coming, and we’re preparing for the deluge of decisions. Stay with us over the next few weeks, it’s going to be a ride!

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!