Channel

Interview | Justice Indira Banerjee, former judge of the Supreme Court

Justice Indira Banerjee spoke with Gauri Kashyap, SCO, about the Court's pendency problems, need for capacity building for women and more

Transcript

Gauri Kashyap: Hello everyone, welcome to SCO’s channel. I’m Gauri Kashyap and today I’m honored on this special day to be joined by Justice Indira Banerjee, former judge of the Supreme Court. Ma’am thank you for joining us today. We’d just like to ask you a few questions: some reminiscing about your time at the Supreme Court, some perhaps commenting on the Supreme Court, like observers like us, and some as your experience as a woman in the legal profession.

So first off: your journey in the legal system began in 1985. Could you tell us a little bit about what it was like to be a young woman lawyer in the courts back then?

Justice Indira Banerjee: Getting a chamber, getting a senior to mentor you was difficult but I was lucky to get a very good senior who was very supportive—Mr Samaraditya Pal. But before that I had been to at least four chambers—four seniors who said they didn’t take ladies in their chamber. This was one.

Secondly sexist jokes and remarks. I remember a slightly senior solicitor commenting “oh you’ve come to the profession. When you get a blasting from the judge you’ll run to get married. You’ll get married and run away.” So I said let’s see.

Gauri: And here you are!

Justice Banerjee: I jokingly told him I didn’t blast you. I could have.

Gauri: Since then ma’am, 37 years later, how do you see the court has changed?

Justice Banerjee: A lot has changed because there are many more women in the profession. There are many more judges. But there should be greater change.

Gauri: During your time at the Supreme Court I think you saw one of the world’s biggest crises in recent times. You were there when the Supreme Court was working its way through the covid crisis. In many ways the Supreme Court’s functioning was halted and in many ways it was forced to adapt. Could you share some experiences from your time there as a judge?

Justice Banerjee: There was technical upgradation almost overnight. We started taking up cases online. There were lesser number of benches. In fact just before the covid pandemic set in, I had started to preside over a bench. But after the covid pandemic set in I again became the second judge, third judge, in a bench because we used to have only five or six benches.

Gauri: What were some of the bigger challenges at that time?

Justice Banerjee: I had some idea of computers. So it was not that much of a challenge.

But yes I had a P.A. She had a small child. Before the pandemic started she used to leave her child in the creche. After the pandemic started the creche closed and under the rules children were not allowed to be taken out at all. You can’t leave a child alone so sometimes she had to stay back at home. Sometimes her husband had to stay back at home.

So that was impacting my work and I thought I had to cooperate and help her out even though my work was piling up and I was facing difficulty.

Gauri: During that time, before COVID-19 struck, pendency was at about 59,000 cases. And by the time the court regained its complete functioning by about 2021 pendency had increased by over 10,000 cases. And this is not just a covid related issue, right. Over the years we’ve had an astronomical increase. What can the court do, realistically speaking?

Justice Banerjee: The courts have to be a little strict to weed out frivolous litigation. And the statistics are not always a very clear reflection.

Gauri: What are we missing?

Justice Banerjee: I’ll tell you the reason. Just after my elevation to the High Court I was on the Division Bench. And every Friday the Division Dench used to take up part-heard cases. So I used to be given a single bench. Probably because I was newly elevated they used to give me old cases. I found most of these cases had become infructuous, either because there was a decision one way or the other by the Supreme Court, or there were a whole lot of matters which had to be transferred to the land tribunal because of a change in law. Administrative tribunal matters which were still there in the High Court.

So I used to take up these matters and I used to dismiss and if there were matters which had to be transferred to the tribunal I used to pass orders straight away for transfer.

So one day a senior colleague of mine told me “Indira you’re dismissing these matters on the first day itself!” So I said “I’ve told the bar that if they come and mention it before me I’ll restore it immediately.” In the 14 and a half years that I was in the Kolkata High Court no one came back to mention those matters.

When I was taking on these matters my Chief Justice, Justice Ashok Mathur said that I had very good disposal figures. I smiled and I said only buried the dead. It’s also also important that we sometimes save the dying rather than dispose of the dead.

Gauri: So it’s a two-part system. One is at entry there is frivolous petition and perhaps at disposal no matter what judges do it’s this entry clogging that messes up the system.

Justice Banerjee: Law changes. There is a decision of a higher court. Now you should probably have a case management setup comprising of some lawyers also, who would earmark such cases which have become infructuous so that they can just be thrown out of the list. The registry can do some weeding out, provided the lawyers cooperate. Otherwise they go by the numbers, the case. It may not be possible for them to know.

There are other things which have been controlled. Once upon a time they used to have multiple petitions without disclosing that the petition had already been disposed of. But now with the computerisation you know one can just log in and see the result of the case. So if there’s an order if it has already been disposed of, the disposed of matter won’t come in the list again.

I can tell you what I did in the High Court. Get similar matters grouped and get them disposed off together. Here on one occasion I remember my court master came to me. This was a batch of Income Tax Matters, in which certain provisions of the income tax act with regard to settlement of disputes were under challenge. The matter was argued by one of the senior most Counsel. The additional solicitor general gave his response. Then the counsel for the petitioner said he had a constitutional matter in the Supreme Court so he wanted some time. I gave them time.

My court master came and said, “My Lord, release these matters from your list.” So I said “why?” He hesitated a little and he said “My Lord you’re heading the list of part-heards, because of these matters.” Because they were a batch of 65 matters and all of them were coming as part-heard. So I said, “It doesn’t matter, Suresh Babu.” After a few days the matter was disposed of, so I called Suresh Babu and I said “Suresh Babu aren’t you very happy?” He was a bit taken aback. I said “You were concerned about the part-heard matters—that this court was heading the list of part-heard matters. Aren’t you happy now? This Court is heading the list of disposed of matters.” He smiled. I said “don’t smile! It’s only one judgement! It’s only one judgment, one point of law.” Just that 65 matters were tagged together. So if you group the matters then you can have all the matters disposed of. But when you have them separately, then you have to hear them again and again, then they may go to different benches, they may have conflicting decisions. So these are things which have to be done.

But then the Judiciary also has a problem. And that problem is—what happens when you go to a hospital? If it is a hospital with 400 beds they take 400 patients. Maybe they’ll take another 15 patients and accommodate them on the floor or in the corridor, because they are critical patients. After that they’ll say sorry sorry, we can’t do anything about this. But so far as the Judiciary is concerned, the gates of the Judiciary are always open.

Gauri: Part of this is the increasing number of special petitions that are filed. Some commentators say that it’s taking away the role of the Supreme Court as a Constitutional court and is not getting to hear as many Constitution bench cases.

Justice Banerjee: Priority should definitely be given to pending constitutional cases which have to be decided by the Constitutional Court.

Gauri: You were part of many Constitution bench cases yourself, Ma’am. Do you find that the court hearing Constitution bench cases takes away its time to do other things and tackle this massive pile of pendency? Many people find that because Constitution bench cases happen it takes away four or five judges at a time or nine judges or 11 judges at a time which means they can’t clear the many bench cases that are pending. It’s a time allocation question.

Justice Banerjee: No, no. The Supreme Court’s primary duty is to decide cases of constitutional importance so constitutional cases have to be decided. They should not be unnecessarily prolonged but if it requires hearing that has to be done. And once a constitutional case is disposed of by the Constitution Bench many other matters will get a resolution.

Gauri: During your tenure at the Supreme Court you saw five Chief Justices. We’ve seen that depending on the changing of the Chief Justice the tone in tenor of the Court change. Some are media friendly, some are not, some kinds of cases get heard, some not. How do you view the role of the Chief Justice in setting a tone for the court—both in the public eye and how the public sees the court but also its own functioning?

Justice Banerjee: When I was elevated Justice Dipak Mishra was the Chief Justice. I was elevated on 7 August and he retired on 3 or 4 September. So I hardly got him as Chief Justice for 2 months.

The next one was Justice Gogoi. Okay. He was all right as a Chief Justice. He was quite strict.

Next came Justice Bobde. It was the COVID-19 period.

After Justice Bobde came Justice Ramana.

Justice Uday Lalit, when he was the Chief Justice, set up many constitutional benches.

Gauri: 25, he put together.

Justice Banerjee: But I could not do all of them because my brother judges did not agree because they felt they had other more important matters which have to be exposed.

Obviously the Chief Justice is the head of the institution. So his image—whatever the image he creates reflects upon the Judiciary in a big way.

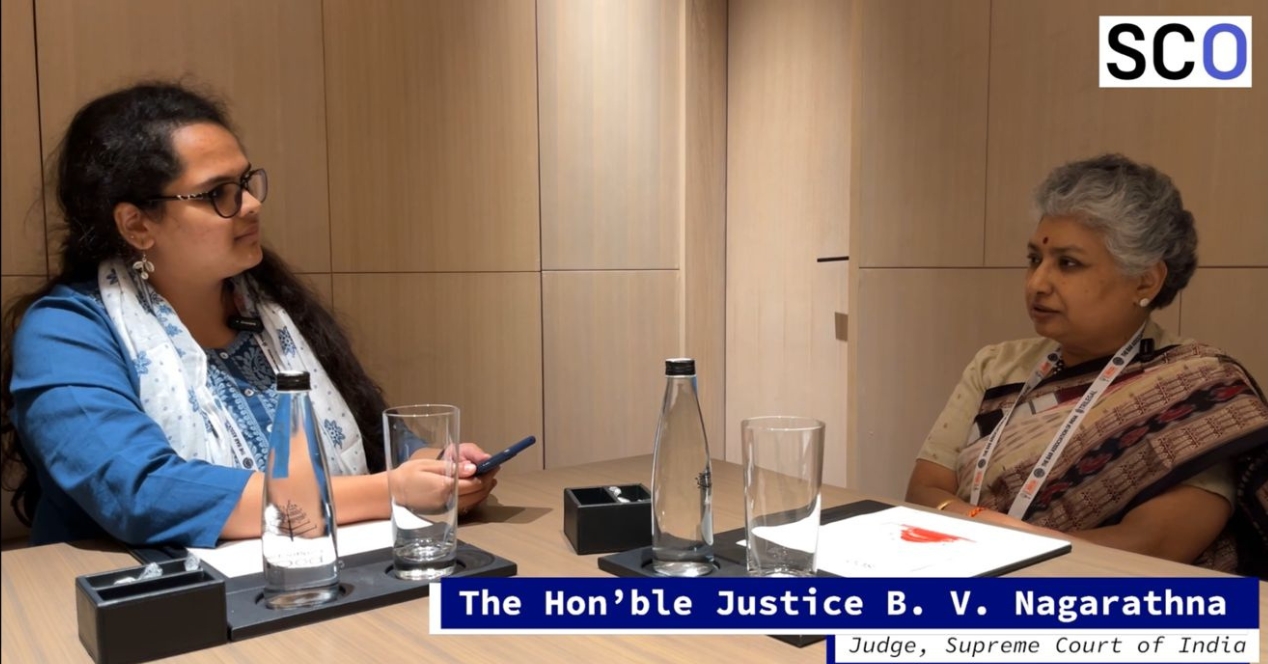

Gauri: At the Supreme Court Observer, we had previously had an opportunity to speak to Justice B.V. Nagarathna particularly about what the Court can do institutionally to improve the quality of women lawyers and women judges in the court. And she had said some institutional changes such as building a creche or you know having those kinds of accesses were important. She also mentioned the need for family support.

Justice Banerjee: Even training. You can even have training of lawyers training of trainers. There are many lawyers who may not be very proficient in English but proceedings are conducted in English. So maybe you can have an English class for them—a spoken English class—which might help them. Then you can have sessions on advocacy. I remember Priya Hingorani. She used to conduct these training sessions for lawyers in different High courts in the country but unfortunately they do not always get the right kind of support.

Gauri: So capacity building for women.

Justice Banerjee: Capacity building. You can also evolve some system where some financial assistance is given to students who are women from the lower economic strata, to enable them to kind of continue to kind of pull on.

But very often many things which we say cannot be implemented. It is difficult to implement.

One of the Chief Justices had perhaps said that the junior lawyers should be paid and paid a minimum amount. On principle there can be no quarrel with this proposition that the Juniors should be paid. But how are you going to enforce it? I, Indira Banerjee, I’m a lawyer and I am not going to select through a competitive process. After this interview I’m impressed with you, you come to my chamber I’ll say I’ll certainly take you. I’m not that impressed with her, I will say I won’t. Can you force me to take a junior in my chamber?

It also depends on my income. It depends on my capacity. There are so many lawyers who approach me saying that they want to be my law clerk, law assistant. But I don’t have a proper office in that sense. I have a residential office. Where do I give them the place to sit? If I don’t know what I’m going to earn the next month, how will I make a commitment to pay a certain amount for the next one year? So it’s all very fine.

The established lawyers, maybe you know the Mukul Rohatgis, the Kapil Sibals, the Abhishek Manu Singhvis—they may be in a position to keep a lot of Juniors and pay them well. But a lawyer who’s not sure of his own income, how will we get into this commitment? And then how do you estimate your future income? Present, past years things may change tomorrow because of a health issue. So what will the lawyer do?

If I’m going to keep one junior, and there is a person from a weaker economic section, someone who is not proficient in English and someone else who’s from a good school, who is good at English, who will be able to correct my drafts—I’ll get proper assistance. I will lean towards that lawyer. You have to achieve a certain level of competence.

Some attempts may be made to ensure that public sector undertakings engage women lawyers, empanel women lawyers.

Gauri: Recent data shows us that about only 15% of nearly 1.8 million people who join the legal profession are women. So on this occasion of international women’s day could you give our viewers a message especially our young women viewers?

Justice Banerjee: I would advise them to come to the legal profession in larger numbers—to work hard, prove their competence, their worth through their performance. And there is always room at the top. You need patience.

They used to say law is a jealous mistress. So you can’t take up law as a part time profession. You can’t say I’ll go to the Disco every evening and I’ll be a lawyer. You can’t say that I’m going to have my fun, I’m going to enjoy life and I’m going to be a lawyer because then you’ll slip back. And at the end of the day some opportunity—one or two opportunities may be given but you have to seize the opportunity to show that you are capable. If you are good, if you are doing well, work will come. People will come. Firms will want to engage you.

I told you a little while ago if you get any benefit as a woman, that’s good but don’t expect it. Excel. And women are excelling! You’ll be happy to know that in many states more than 60%, in one case even 70% of the successful candidates in a Judicial Service Examination were women. The reasons are socioeconomic. Women have to take time out, then they get married. Their social obligations and commitments, maternity leave, child Care leave. There are 101 rules.

Gauri: Thank you very much ma’am. I won’t take more of your time but thank you for sitting down with us today and for speaking with our viewers and us. Thank you once again!

That was the Supreme Court Observer thank you all for watching.