Analysis

From Babri to Sambhal

The top court’s approach to place of worship cases may have emboldened right-wing groups to take the judicial route to open a can of worms

In 1991, Kalyan Singh, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, assured the National Integration Council that his government will “hold itself fully responsible for the protection of the Ram Janma Bhumi-Babri Masjid structures.” In November that year, while hearing a challenge to the acquisition of the Babri site by the state government, the Supreme Court incorporated Singh’s guarantee in an order.

We know what happened a year on: kar sevaks climbed the dome in a planned onslaught, police officials were reportedly ordered to stand back and watch, the mosque was brought down. In the days that followed, nearly 2000 people—mostly Muslims—were killed in riots across the country. In October 1994, Singh was held in contempt (along with the UP government) for breaking his promise to the statutory body. But the punishment was a token one—a day of imprisonment and a fine of ₹2000.

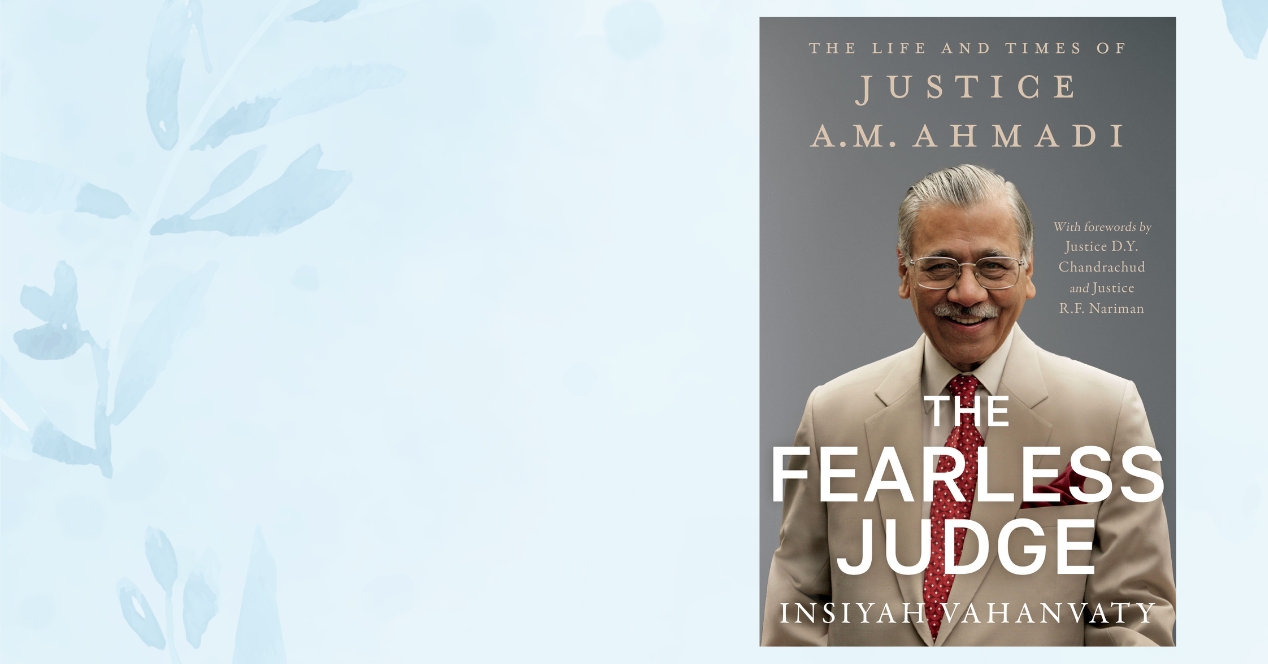

The same day that Singh was found in contempt, a 3:2 majority led by CJI Venkatachaliah upheld the government’s acquisition of the Babri land. Justice A.M Ahmadi, in his own telling, had expressed disagreement with the majority’s draft judgment because it didn’t prescribe any adverse actions against those who participated in the demolition. Ahmadi also wished for the draft judgement to be amended to allot a piece of land “large enough for a moulvy to spread his mat and offer namaaz.” The majority judges outright refused.

There is a straight line running through the Court’s treatment of the Babri matter and the violence that erupted in Uttar Pradesh’s Sambhal city last weekend, where at least five Muslim men were killed. They were protesting the district court-ordered survey of the Shahi Jama Masjid, a 16th century-structure that Hindu groups allege was built on the ruins of a temple. Anas Tanwir, an Advocate on Record, told me that the Supreme Court’s downplaying of the Babri tragedy has played a part in emboldening Hindu groups to lay claim to other Muslim places of worship in North India.

In 2022, twenty-eight years after his father’s dissent, Justice Ahmadi’s son Huzefa Ahmadi argued against permitting a survey of the Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi. Some Hindu groups contend that the mosque was built after the demolition of an ancient Vishveshwar temple. In the Supreme Court, Ahmadi argued that the survey would violate the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991, which states that the “religious character” of a place of worship cannot be changed from its default position as of 15 August 1947.

But in a hearing in May 2022, the presiding judge Justice D.Y. Chandrachud noted aloud that ascertaining the “religious character” of a place of worship was not barred by the Act. By doing so, he introduced a new argument into the litigation—that the “religious character” of Gyanvapi was indeterminate on 15 August 1947. Last week, the Supreme Court issued notice in the matter, seeking a response from the Masjid Committee on the petitioner’s demand for a land survey conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India.

This week, days after the Sambhal tragedy, a district court in Rajasthan admitted a petition seeking a survey of the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, one of the country’s most well-known Sufi shrines. The petition filed by Vishnu Sharma, the national president of an organisation called Hindu Sena, claims that the Dargah was built after demolishing a temple dedicated to the Hindu deity Shiva.

Tanwir’s observation of district courts deriving legitimacy from the Supreme Court’s approach to place of worship cases doesn’t seem like a leap. By going easy on Kalyan Singh, by upholding the UP government’s land acquisition, by awarding the Babri site to the Hindu deity, by opening an interpretive can of worms around the POW Act in the Gyanvapi case, the top court’s approach may have added fuel to the fire.

On Friday, CJI Khanna put a momentary halt on the chaos in Sambhal. He directed the trial court to defer proceedings until the need for a survey was litigated in the High Court. K.M. Nataraj, the Additional Solicitor General, assured the Court that peace will be maintained.

But the broader questions remain, and may be a litmus test. The Khanna Court has an opportunity to put the lid back on a disturbing trend by unequivocally stating that district courts cannot permit the kind of land surveys that have been petitioned for in Sambhal and Ajmer and, that too, without hearing the Muslim defendants. The Court also needs to put the half-baked interpretation of “religious character” in the POW Act to bed. Will the Court be able to dispel the spectre of many Ayodhyas?

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!