Analysis

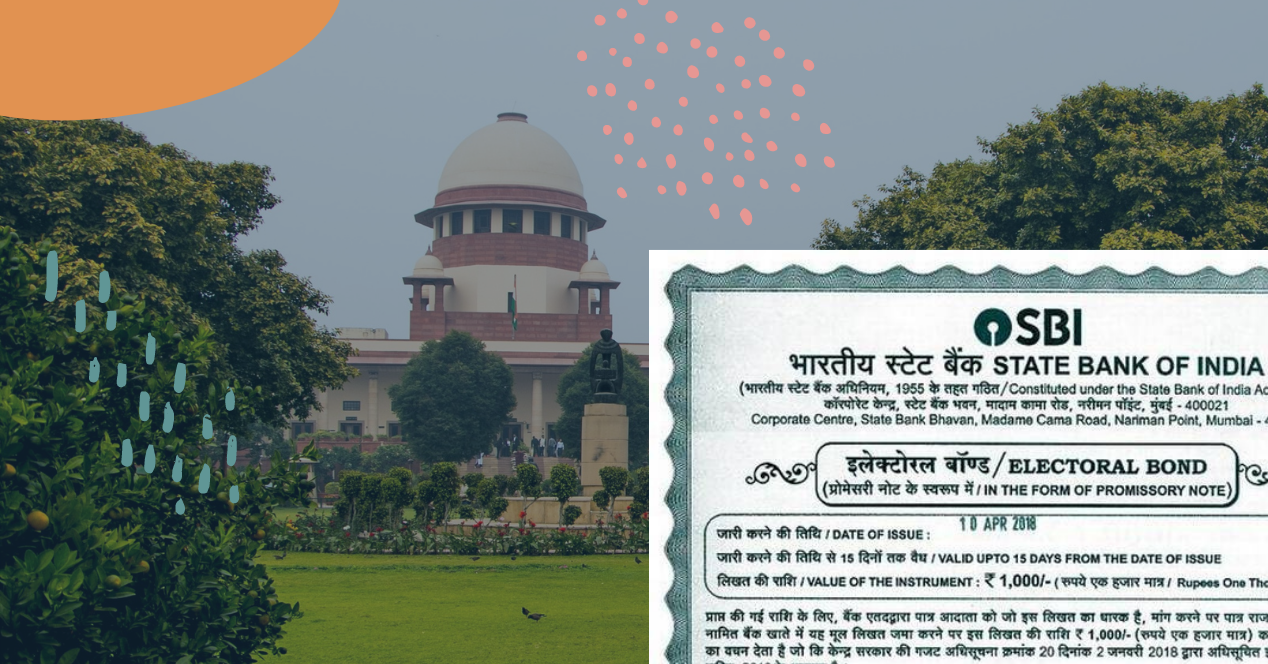

Electoral bonds and democracy: What’s at stake?

Are electoral bonds the future of transparent elections, as the Union government claims, or the instrument of its demise?

In February 2017, during the Union Budget speech, then finance minister Arun Jaitley expressed concern that, even after 70 years of independence, “the country [had] not been able to evolve a transparent method of funding political parties which is vital to the system of free and fair elections.”

In “an effort to cleanse the system of funding of political parties,” the electoral bond scheme was introduced, through amendments to four key legislations—the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act, 2010 (FCRA), Representation of the People Act, 1951 (RoPA), Income Tax Act, 1961 and the Companies Act, 2013. The scheme facilitates anonymous donations to political parties in India, and liberates political parties from any obligation to disclose the source and quantum of such donation.

In October 2023, The Hindu reported that electoral bonds worth ₹11,699.84 crore were sold between March 2018 to December 2022.

Understanding electoral bonds

An electoral bond is akin to a promissory note. The Union introduced the Electoral Bond Scheme, 2018 through a notification issued on 2 January 2018. However, an electoral bond does “not carry the name of the buyer or payee,” facilitating anonymity of a donor. Any person who is a “citizen of India or incorporated or established in India” can buy bonds “singly or jointly with other individuals.” Only authorised branches of the State Bank of India (SBI) are allowed to issue electoral bonds. One may apply to purchase an electoral bond in person at an authorised branch of SBI or apply online on its website.

Electoral bonds are issued in denominations of ₹1000, ₹10,000, ₹1,00,000, ₹10,00,000 and ₹1,00,00,000. They are sold for 10 days in January, April, July, and October each year under the 2018 scheme.

Only a political party, registered under RoPA, which secured more than 1 percent of votes in the “last general election to the House of the People or the Legislative Assembly, as the case may be,” can encash such a bond. Once issued, the political party must encash it within 15 days, failing which SBI will donate that sum to the Prime Minister Relief Fund.

Laws amended to facilitate the electoral bonds scheme

Section 236 of the Finance Act, 2016 introduced changes to the first of the four laws of the electoral bonds framework. It amended Section 2(1)(j)(vi) of the FCRA, which defines “foreign source”, to allow foreign companies who have majority share in Indian companies to donate to political parties. Previously, foreign companies could not donate to political parties under the FCRA and the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999.

Section 11 of the Finance Act, 2017 amended Section 13A of the Income Tax Act, 1961, exempting political parties from their obligation to keep a detailed record of contributions received through electoral bonds.

Section 135 of the Finance Act, 2017 amended Section 31 of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934, permitting the Union government to “authorise any scheduled bank to issue electoral bond[s].”

Section 137 of the Finance Act, 2017 introduced a proviso to Section 29C of RoPA, which mandates the publication of “Contribution Reports” which discloses “contribution in excess of twenty thousand rupees” from companies and individuals. The amendment exempted political parties from this obligation for contributions received through electoral bonds.

Section 154 of the Finance Act, 2017 amended Section 182 of the Companies Act, 2013, removing the upper limit on how much a company could donate to a political party. Previously companies could only donate up to 7.5 percent of three years of the company’s net profits.

PILs challenging scheme in the Supreme Court

Soon after the 2017 Finance Act was introduced, two NGOs—the Association for Democratic Reforms and Common Cause—as well as the Communist Party of India (Marxist) filed a Public Interest Litigation case against the scheme. They argued that the scheme legitimised “electoral corruption at a huge scale” and ensured “complete non-transparency in political funding.”

More specifically, they contended that the Finance Acts of 2016 and 2017 were unlawfully passed as money bills under Article 110 of the Constitution of India, 1950, thereby bypassing the examination of the respective bills by the Rajya Sabha.

They argue that exempting political parties from their obligation to disclose the source of funding violates voters’ right to information about their electoral candidates.

The electoral bonds scheme, the petitioners argue, ran counter to the goals Jaitly declared in the Union Budget speech—they created greater opacity in election funding, and facilitated a higher degree of corruption and external interference in India’s elections.

Election Commission affidavit: Electoral bonds threaten transparency

On 25 March 2019, the Election Commission of India (ECI) filed an affidavit that raised strong objections to the electoral bonds scheme.

According to the affidavit, the ECI, in a letter dated 26 May 2017, “informed the Ministry of Law and Justice that certain provisions of the Finance Act, 2017…will have serious repercussions/impact on the transparency aspect of political finance/funding.”

The ECI also warned that in the absence of a mandate to submit Contribution Reports, there was no way to ascertain whether a party had taken any donations from companies and foreign sources. They warned that allowing foreign companies with majority shares in Indian companies would “allow unchecked foreign funding of political parties in India, which could lead to Indian policies being influenced by foreign companies.”

The Union government, through the finance ministry, filed a rejoinder six days later, claiming that under the “old system” a “major proportion” of funding was in the form of cash which caused an “unregulated flow of black money” in political funding. Further, they claimed that donors were apprehensive of “competitive pressure” from different political parties if they disclosed who they were funding. They argued that the electoral bonds scheme was introduced “considering the need to impart greater accountability…as well as to maintain anonymity of the donor.”

The Union also assured that no black money could be used for purchase as there is only one authorised bank—State Bank of India—that can issue such bonds. Further, providing KYC (Know Your Customer) details ensured accountability.

Six years of the case in the Supreme Court

In three days of hearing in April 2019, the Court contemplated whether the scheme should be stayed to stop the collection of funds until the hearings are concluded. A three-judge Bench of the Supreme Court comprising Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi, and Justices Deepak Gupta and Sanjiv Khanna found that the “weighty issues” in the case “cannot be concluded…within the limited time that is available before the process of funding through the Electoral Bonds comes to a closure.”

Instead, it directed all political parties who have received funds through electoral bonds to submit “detailed particulars of the donors as against each Bond,” including the amount and bank particulars, in a sealed cover to the ECI. The sealed covers would remain in the ECI’s custody until the court directed otherwise.

In January 2020, the Court heard another plea by Association for Democratic Reforms, but did not issue any directions. In 2021, an application was filed to seek a stay of the scheme before the commencement of a fresh round of bond sales. This time, the Bench headed by Chief Justice Bobde pointed out “that there cannot be repeated applications seeking the same relief, merely because the interim reliefs sought relates to something that is to happen at periodical intervals of time.”

Further, the Court noted that the safeguards suggested by the Reserve Bank of India were incorporated in the scheme, and they saw no “justification for the grant of stay at this stage.”

On 10 October 2023, petitioners reportedly approached the Court to hear the case prior to the 2024 General Elections. On 16 October 2023, a three-judge Bench of Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Justices J.B. Pardiwala and Manoj Misra heard the case. CJI Chandrachud, during mentioning, stated that an application had been made to refer the case to a larger bench owing to the “importance of the issue.” The case was referred to a five-judge Constitution Bench

Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, Justices Sanjiv Khanna, B.R. Gavai, J.B. Pardiwala and Manoj Misra will hear the case from 31 October 2023.