Analysis

Commissions and Omissions

How will the executive-judiciary tussle around appointments play out in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s third term?

In 2014, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s election manifesto included a list of 22 ambitious reforms on the judicial front. One of those was the formation of a National Commission to recommend appointments to the higher judiciary.

Three months after it came into power, the Narendra Modi-led government followed up on its promise. The 99th Constitutional Amendment Act created a National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC). Its six members included the Chief Justice, two senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the Union Law Minister and two “eminent” persons nominated by a committee comprising the CJI, Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition. Any two members of the NJAC could veto a recommendation.

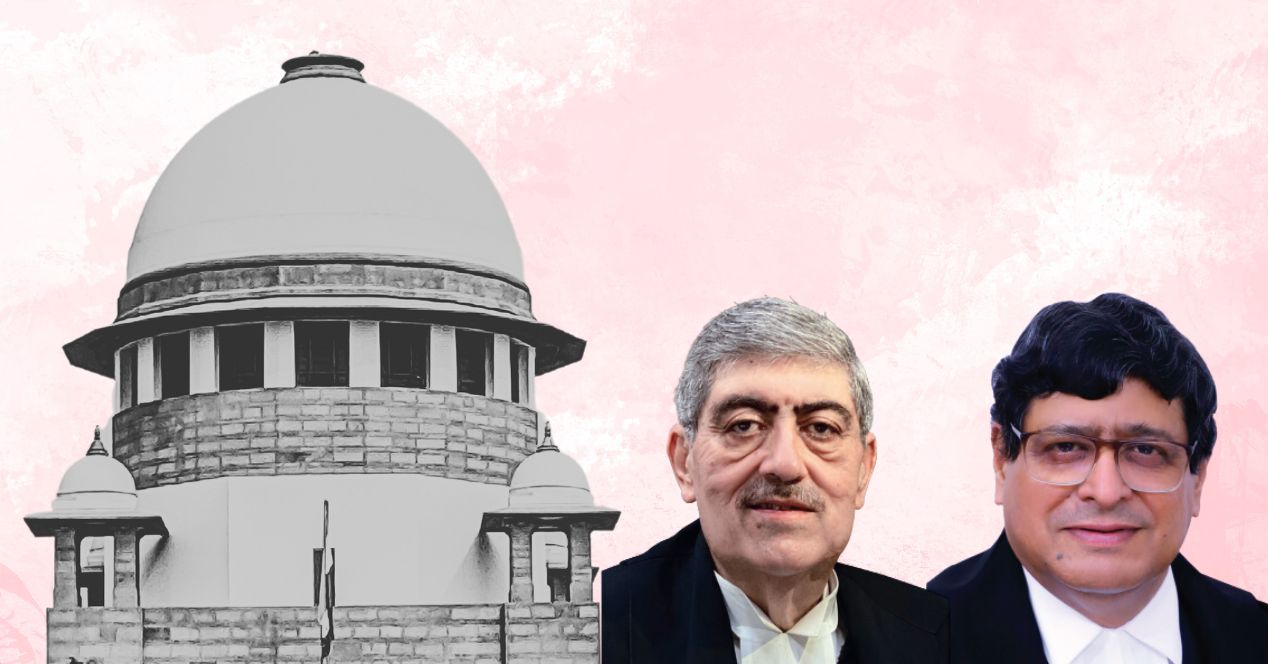

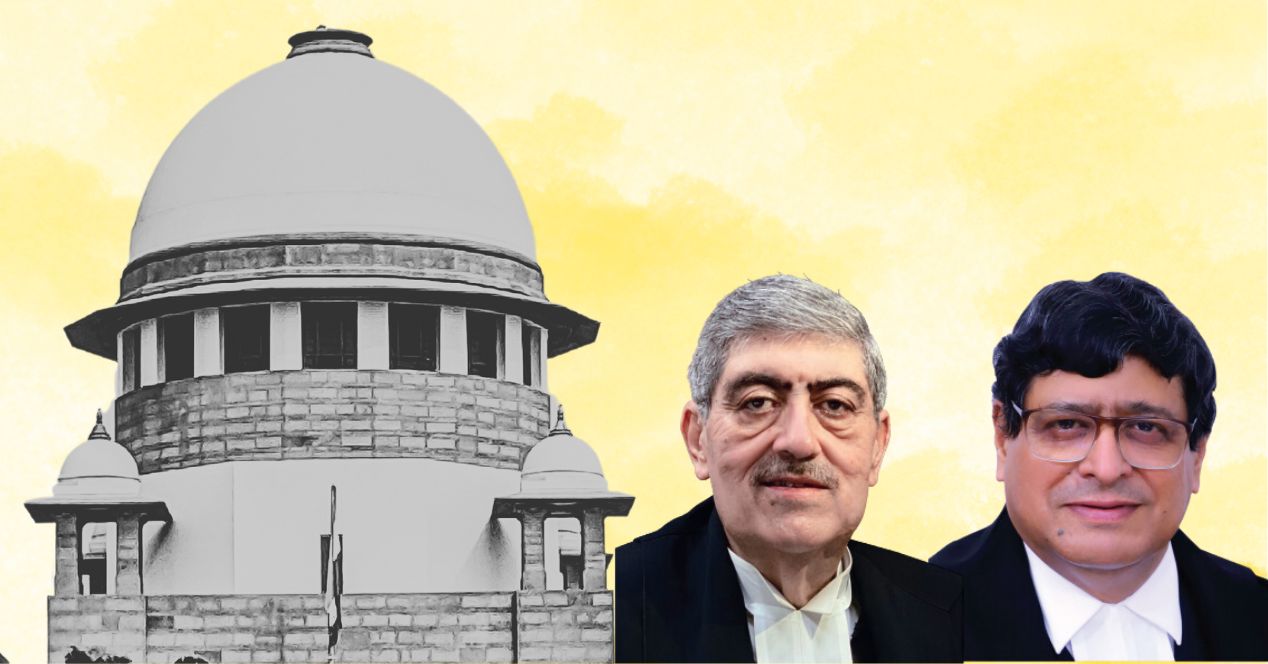

In October 2015, the Amendment was struck down as unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in what is known as the Fourth Judges Case. Even as the decision acknowledged that the process could be made more transparent, it reinstated the Collegium system, under which appointments are recommended by the five senior-most judges of the Supreme Court. The judgement set the stage for heightened tensions between the executive and judiciary.

Since 2015, the Modi government has been called out several times for delays in notifying the recommendations of the Collegium. In 2016, then Chief Justice T.S. Thakur pleaded with the government to address the issue of judicial vacancies, which reportedly peaked at 45 percent in the middle of that year. Eight years later, 30 percent of the seats in High Courts continue to remain vacant.

Also in 2016, the Thakur-led Court had sent back a draft Memorandum of Procedure for the selection of High Court judges on the ground that some clauses were “not in harmony” with the independent functioning of the judiciary.

The battle lines were drawn in the open. Through his tenure, Law Minister Kiren Rijiju came down heavily—and publicly—on what he perceived as a lack of transparency and inordinate delays in appointments. His stand-off with the Supreme Court was surmised as the reason for his departure from the portfolio in May 2023.

In the last few years, the government has worked around Supreme Court decisions centered on tenures and appointments in institutions like the Central Bureau of Investigation, the Enforcement Directorate and the Election Commission of India. But the NJAC decision has proved harder to sidestep because of its constitutional implications (The CBI/ED matter was an ordinance; in the ECI case, the Court-appointed Commission was meant to be a stop-gap until Parliament legislated.)

Through all this time, the Court has stood its ground. In 2022, the Court reprimanded the Centre for not approving recommendations that had been reiterated by the Collegium. Justice S.K. Kaul remarked that this was because the government was “not happy” with the NJAC judgement. Last year, Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud defended the system stating that the Collegium applied “well-defined” parameters. In November last year, the Court pulled up the Centre in a contempt petition for selective appointments and leaving recommendations in limbo.

In the run-up to the 2019 and 2024 elections, the BJP’s promises on the judicial front were glorified footnotes at best, with not more than three points of reform. Neither manifesto mentioned a commission for judicial appointments. But the developments of the last decade indicate that the topic is far from a dead issue for the BJP, which is now on the verge of forming a government again for the third consecutive time.

Only a couple weeks ago, former minister Upendra Kushwaha stated that on returning to power, the NDA will make a fresh attempt to scrap the “undemocratic” Collegium system. The comment was made in the presence of Home Minister Amit Shah.

There are many moving pieces to this plot. For one, after CJI Chandrachud’s retirement in November 2024, the executive will interact with seven different Chief Justices. For another, the return to coalition politics in the 18th Lok Sabha might mean that the BJP will have to prioritise its battles in the legislative and judicial arenas. It will be interesting to see how this tussle plays out in the third term.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!