Analysis

Chief-in-waiting: New door opened by Collegium in its Justice Bagchi recommendation

If ‘in-line-to-be-CJI’ is now a relevant consideration for SC elevation, we examine how the Collegium might have picked Justice Bagchi

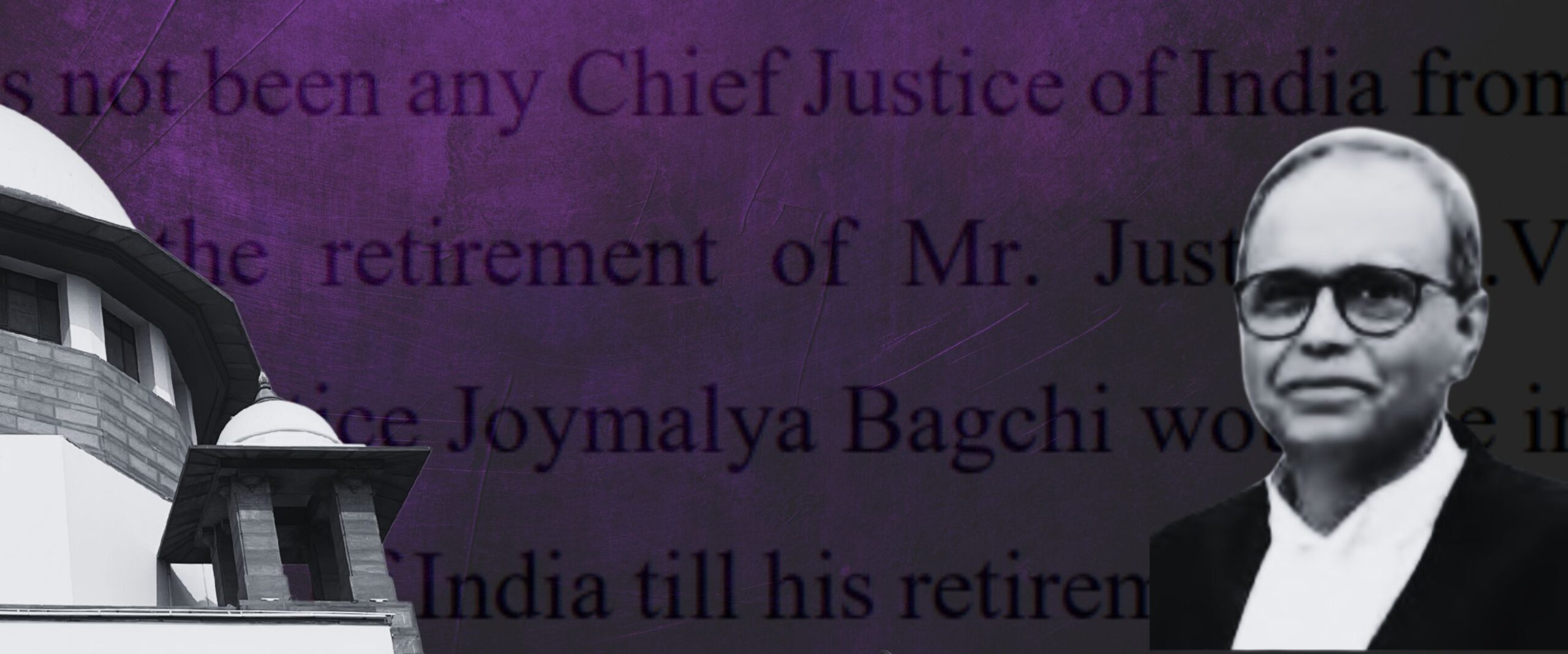

The Supreme Court’s Collegium’s recent recommendation for the elevation of Justice Joymalya Bagchi of the Calcutta High Court raised interesting issues. The fact that he will be in line to become the Chief Justice of India in mid-2031 was specifically called out as a factor influencing the recommendation. The statement also noted that there hasn’t been a CJI from the Calcutta High Court since the retirement of Justice Altamas Kabir in 2013. By the time Justice Bagchi succeeds Justice K.V. Viswanathan on 25 May 2031, he will have had a tenure of more than six years in the top court. Justice Bagchi’s tenure as CJI will be a short one, just a few days over four months.

By now, it is well-established that the Collegium considers factors beyond rank seniority while recommending elevation to the Supreme Court. Recent resolutions make it clear that the Collegium considers merit, integrity, competence and several other considerations (which include but are not limited to regional, caste, gender and minority community representation).

The Justice Bagchi resolution brings to the fore two more factors that the Collegium could consider in the context of a recommendation: (a) in line for CJI-ship; and (b) representation of particular high courts in the office of the CJI.

Why was Justice Bagchi preferred over judges senior to him?

In a list of all high court judges in India, Justice Bagchi appears at Serial Number 11 when it comes to seniority. The Collegium emphasised Justice Bagchi’s long tenure as a high court judge and his significant experience in diverse fields of law. The Collegium also called out the fact that there is only one judge from the Calcutta High Court on the Supreme Court bench presently—Justice Dipankar Dutta.

In the table below, we list details about the 10 judges who are senior to Justice Bagchi in the all-India list. To compile the list, we surveyed the latest list of judges on the websites of all of India’s high courts as of 17 March 2025. Justice Bacghi’s date of initial appointment was 27 June 2011. Had he not been elevated, he would have retired from the Calcutta High Court on 2 October 2028.

It’s clear that the Collegium didn’t only intend to respect the regional representation imperative because four judges who are senior to Justice Bagchi have their parent High Court as Calcutta. All of them are set to retire earlier than Justice Bagchi. That ‘in-line-to-be-CJI’ was a decisive factor is clear from the fact that all of them would have been age-barred by the time Justice Viswanathan retires in May 2031.

Similarly, the remaining six judges on this list are set to retire earlier than Justice Bagchi. All of them would have crossed the age of 65 by the time Justice Viswanathan retires in May 2031.

Why was Justice Bagchi preferred over high court CJIs junior to him?

There is a contention that the tenure of Justice Bagchi’s expected CJI-ship is too short and doesn’t justify his being recommended over other judges who may have a longer tenure as CJI.

Given that none of the 10 senior-most high court judges would have been of eligible age at the time of Justice Viswanathan’s retirement, let us consider judges who are junior to Justice Bagchi.

In fact, we can further narrow down the list to junior judges who are currently serving as CJ in various high courts, considering that our survey of high court judge rosters didn’t show any puisne judges who could have a longer tenure than Justice Bagchi, were they to be elevated to the Supreme Court.

Here, too, the Collegium’s choice appears limited. All the judges in the table listed above are scheduled to retire prior to the date of Justice Bagchi’s retirement as high court judge. With the exception of M.S. Sri Ramachandra Rao, were they to be elevated to the Supreme Court, they would hit the Supreme Court’s retirement age of 65 before Justice Viswanathan leaves office. Admittedly, Justice Rao could have succeeded Justice Viswanathan as CJI, but his term would be restricted to less than three months, even shorter than Justice Bagchi’s expected run as CJI.

If the Collegium had to pick an existing high court CJ with an expected CJI tenure longer than that of Justice Bagchi, the next option would be CJ Arun Bhansali of the Allahabad High Court (his parent high court is Rajasthan). His date of high court retirement is 14 October 2029, so he would have had more than a year’s run as CJI were he to be elevated at this time. But perhaps the Collegium felt that his time hadn’t yet come—besides, the Calcutta regional representation factor would have to be discounted if they were to recommend Justice Bhansali at this time. All this would make it appear that Justice Bagchi’s choice was well-considered in the circumstances.

Has ‘in-line-to-be-CJI’ been considered as a factor before?

The ‘in-line-to-be-CJI’ factor was not considered for the 10 judges who have been appointed to the Supreme Court after Justice Viswanathan’s appointment on 19 May 2023. Also, nine judges appointed prior to Justice Viswanathan were recommended by the Collegium despite all of them having to retire before Justice J.B. Pardiwala, who is expected to leave the CJI’s office on 11 August 2030, after serving for 2 years and 3 months.

The resolutions recommending the appointment of seven ‘in-line-to-be-CJI’ judges before Justice Viswanathan were silent on the matter. The first time the Collegium expressly mentioned the ‘in line’ factor in its resolution was in the case of Justice Viswanathan. The Collegium’s reference to Justice Bagchi’s possible succession as the CJI in 2031 in its recent statement may suggest that it is simply continuing a practice that began in 2023 at the time of Justice Viswanathan’s elevation.

However, there is a difference between these two resolutions. The resolution for Justice Viswanathan’s elevation mentioned his eventual CJI-ship only in passing, focussing instead on his legal acumen and suitability. But Justice Bagchi’s appointment makes it clear that his future CJI-ship was a key factor in the recommendation.

Madan B. Lokur, a former judge in the Supreme Court, expressed his reservation about the declaration of the ‘in line’ factor in the Collegium’s statement. “What if the Government refuses to follow the seniority convention in 2031?” he asked. He noted that the consideration of a judge’s potential to succeed as the CJI in future could mean a failure to recommend an otherwise meritorious judge.

Legal scholar Alok Prasanna Kumar seems to have a somewhat different view. In an article for The Economic and Political Weekly in April 2020, he noted that the tenure of a judge expected to be a CJI and one not expected to be a CJI is fairly different. A judge expected to be a CJI is usually appointed around the age of 54; a puisne judge usually enters the Court around the age of 60.

In his 2014 book The Informal Constitution: Unwritten Criteria in Selecting Judges for the Supreme Court of India, advocate and author Abhinav Chandrachud makes the point that serving on the Supreme Court has almost become a “legitimate expectation” for high court judges. In this view of the world, appointing judges to the Supreme Court on the basis of their retirement dates, and to fix CJI succession in future, will mean a fresh setback to the legitimate expectations of high court judges.

As a solution to the problem of limited tenure of CJIs, Chandrachud recommends scrapping the retirement age gap between High Court (62) and Supreme Court (65) judges, accompanied by a policy on the minimum tenure which Supreme Court judges should serve.