Channel

Challenge to the Electoral Bonds Scheme | Day 1

On Day 1, petitioners argued that anonymous corporate funding decimates a representative democracy

Transcript:

Hello everyone and welcome to SCO Daily. I’m Gauri Kashyap and today I’ll be breaking down arguments made on day 1 of hearings in the challenge to the 2018 electoral bonds scheme.

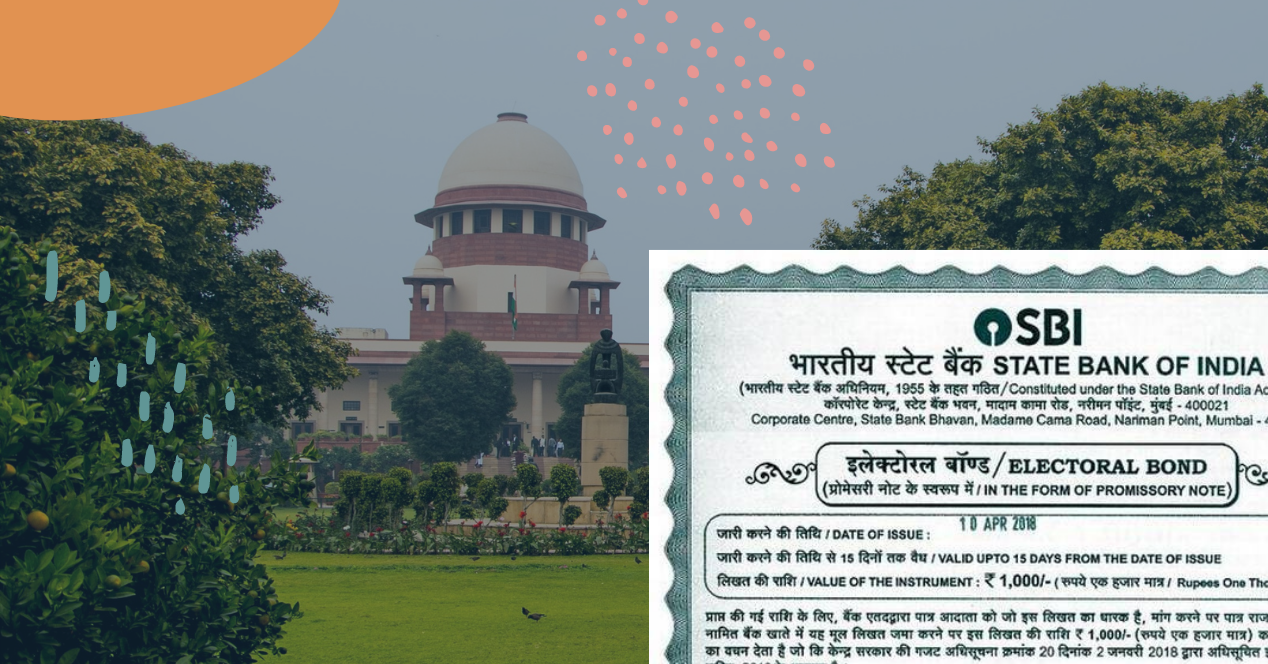

The electoral bonds scheme facilitates anonymous political funding. The scheme was frist introduced in the 2017-18 Union Budget as a way to “cleanse the system” of political funding. NGOs Association of Democratic reforms, Common Cause and the Communist Party of India (Marxist) filed petitions in the Supreme Court challenging the amendments arguing that the scheme allowed “non-transparency in political funding” and legitimised electoral corruption at a “huge scale.”

In October 2023, Advocate Prashanth Bhushan for Association of Democratic reforms asked for the case to be heard at the earliest, in light of the upcoming 2024 general elections.

On Day 1 of arguments, Bhushan argued that non-disclosure of the details of the buyer meant that the larger public could not access information on which political party was being funded by whom. Even the Election Commission of India was privy only to the quantum of donation—not its source.

In an interim order from 2021, the Supreme Court had said that the transactions are not “behind iron curtains” and that “all that is required is a little more effort to cull out such information.” Noting that financial statements of companies were easily accessible on the Ministry of Corporate Affairs website and that political parties filed mandated statements of accounts, the Court had held that the information could be put together using a “match the following” approach. Bhushan argued that there are 23,00,000 registered companies in India and one would have to comb through it all to ascertain how much each company had donated. “Ordinary citizens,” he said, could not collect this information.

Bhushan then read out Jayantilal Ranchhoddas Koticha v Tata Iron And Steel Co. Ltd. (1975) where Justice M.C. Chagla said that “Democracy cannot function unless the voters have all the necessary information about the parties for whom they are going to vote.” This went hand in hand with Union of India v Association for Democratic Reforms (2002) in which the Court held that freedom of speech and expression included the “right to get material information with regard to a candidate who is contesting elections.”

Farasat, appearing for The Communist Party of India (Marxist) added that the electoral bonds scheme was a “legally ordained information blackhole” and that it violates the idea of an “informed electorate” under Articles 19(1)(a) and 326.

Bhushan then argued that the scheme ensures that only government agencies, namely, the State Bank of India and law enforcement agencies can access this information. In that sense, the ruling party could, after exerting some pressure, ascertain the details of the donations.

Sibal brought in another angle to this concern. “Let’s talk practical politics,” he said, arguing that any corporation that makes a sizable donation will themselves disclose information to the political party, in return for favours. Therefore, in reality, political parties need not go to the SBI seeking details of the donor—they themselves will come forward with that information, he said.

“Instead of breaking a rule or regulation, the [electoral bonds] system is bent enough to benefit” the corporate sector, Bhushan argued. With no way to track sources of political financing, quid pro quo, kickbacks and money laundering have become rampant.

Bhushan referred to the Association of Democratic Reforms’ Report on “Electoral bonds and opacity of political funding” which found that 94.25% (₹12,999 crore) of all the bonds purchased between March 2018 andJuly 2023 were in the denomination of ₹1 crore. Therefore, ADR concluded that this meant that the bonds were being purchased by corporations, not individuals. Bhushan added that the unequal use of “money power” through electoral bonds is “making the playing field” between the ruling party and the opposition and other individual candidates, uneven

The Bench noted that though before the electoral bonds regime was introduced, corporate companies could still donate to political parties. However a limit was set to how much could be donated, at 7.5 per cent of three years of the company’s net profits. Further, they had the obligation to disclose such a donation, subjecting such a transaction to public scrutiny. Under the 2018 scheme, anonymity was maintained not just between the donor and recipient, but with society at large as well.

Sibal submitted that “capital and influence go hand in hand. In a market economy, capital symbolises power.” In his written submissions, he stated that quid pro quo is not always direct. The “influence of large political donations is indirect and subtle,” as they give corporations heightened access to lawmakers who can introduce favourable policies. This, he argued, “severs the link between the voter and the representative.”

Sibal went on to argue that the real effect of the electoral bonds scheme was vastly unrelated to elections itself. “There is nothing in the scheme,” he said, “which connects the donation made to the participation in the electoral process. It is a means for political parties to be enriched.”

He took the Court’s attention to SBI’s FAQ section, which clarified that a political party may use the account it creates (to redeem the bonds), for any other operations. Further, the party may continue to use the account after the election “for normal Banking operations”, and may close the account “at any point in time. This meant that a political party could receive funds, close the account and use it for absolutely nothing. There is no spending requirement and no accountability.

Sibal argued that the electoral bond scheme eliminated any requirements to disclose the details of political donations by corporations to their shareholders. In his written submissions, he argued that the scheme permits the “Board of Directors to forgo their fiduciary duty towards its shareholders” and to “hide” the details of which political party the company has funded.

Both Bhushan and Sibal argued that if they so wished, a company could make losses to “funnel money” to political parties “without any transparency and shareholder oversight.” Shareholders completely lose their agency to decide how a company owned by them should “act politically”.

Farasat argued that the scheme went “against popular democracy and shareholder democracy.” He argued that political views are a part of the right to conscience under Article 25. Each shareholder may have a certain political view, which they cannot exercise if they are not made privy to which political party their company is donating to.

With this, the court completed its first day of the Challenge to the Electoral Bonds Scheme hearings.

Read our detailed report on this case at SCObserver.in. Don’t forget to subscribe to us on YouTube, whatsapp or telegram, where we’ll be posting key updates from the top court and explainers on cases that matter to you and me.