Analysis

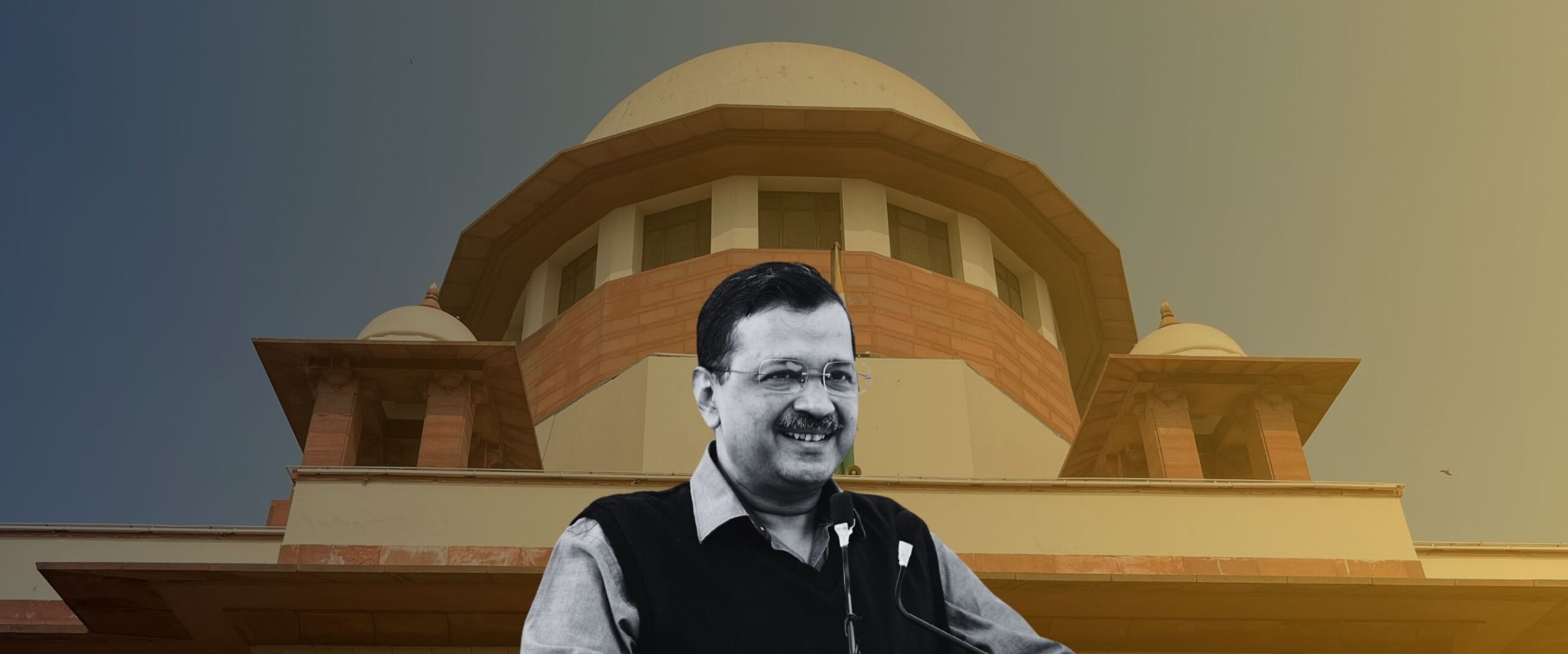

Arvind Kejriwal’s challenge to ED arrest: Judgement Summary

The Supreme Court granted interim bail to Kejriwal. Meanwhile, the legality of his arrest was referred to a larger bench

On 12 July 2024, a Division Bench of the Supreme Court granted interim bail to Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal who was arrested by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) for alleged corruption and money laundering in the Delhi Liquor Policy scam of 2022. It was alleged by the ED that the policy was designed by the Delhi Government, led by Chief Minister Kejriwal, to favour leaders of the Aam Aadmi Party and to provide preferential treatment to private entities involved in the liquor business.

A bench of Justices Sanjiv Khanna and Dipankar Datta held that Kejriwal should be released on bail until the validity of his arrest is determined by a larger bench.

Background

Kejriwal was arrested by the Enforcement Directorate on 21 March 2024, under Section 19 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002. The ED alleged that Kejriwal was the “kingpin” of the liquor policy scam, contending that he colluded with the ministers of the Delhi Government to launder money and engaged in corrupt practices while formulating the now-scrapped policy. Notably, several AAP leaders, including former Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia, have been arrested in the same case.

Kejriwal challenged the legality of his arrest at the Delhi High Court through a writ petition under Article 226 of the Constitution. Article 226 grants high courts original jurisdiction to hear cases. He argued that the arrest was not valid under Section 19 which requires that:

- The arrest has to be on the basis of material in possession with the ED

- There is reason to believe that the accused is guilty of the offence, with the reason for arrest recorded in writing

- The grounds for arrest should be communicated with the accused

The Delhi High Court upheld the arrest stating that the ED had adequate material to demonstrate that Kejriwal was actively involved in concealing “proceeds of crime.” Kejriwal appealed against the decision at the Supreme Court in April 2024. Justices Khanna and Datta began hearing arguments on 30 April.

Senior Advocate Abhishek Manu Singhvi appeared for Kejriwal. He argued that the ED had no sufficient material evidence and relied on insubstantial statements made by unreliable witnesses. He alleged that the witnesses were coerced into falsely implicating Kejriwal. Singvi also argued that the ED selectively hand picked statements and disregarded accounts that absolved Kejriwal.

Further, he claimed that Kejriwal was arrested a week into the Model Code of Conduct (MCC), when the investigation had been ongoing for over 1.5 years, implying that the arrest was a political move by the ruling party. He pointed out the prosecution complaints and the Enforcement Case Information Reports filed in the case had not mentioned Kejriwal at the time of his arrest. A prosecution complaint is an equivalent term for a charge sheet under PMLA cases. Singvi pointed out that despite the lack of any mention, Kejriwal was implicated at a suspicious time in the election cycle.

The ED responded that the arrest was a part of the ongoing investigation into the liquor scam. Section 19 of the PMLA allowed the ED to make arrests without a prosecution complaint being filed against the arrestee in the case.

On Kejriwal’s challenge to the validity of the witness statements, the ED contended that to establish the “reasons to believe” that a person is guilty, the investigating officer need not conduct a “mini trial.” If there are statements implicating an accused, arrest is justified. Moreover, they argued that a Court of law cannot consider the legality of an arrest under PMLA while the investigation is still underway.

The Supreme Court granted interim bail to Kejriwal in the run up to polling day in Delhi for the 2024 General Elections. He was released on 10 May 2024 to campaign for the Delhi polls, on the condition that he would surrender on 1 June. On 17 May, the Bench reserved judgement in the case. This article summarises this 64 page judgement.

Arrests under PMLA subject to “judicial scrutiny”

The ED had argued that the Court cannot consider the validity of an arrest in an ongoing investigation. Rejecting this contention, the Bench held that the power of judicial review extends to arrests made under Section 19 of the PMLA. Section 19 imposes conditions to arrest an individual under charges of money laundering. The Bench noted that these conditions “act as stringent safeguards to protect life and liberty of individuals” against arbitrary arrests, as arrests under the PMLA can be made without a warrant. The two-judge bench held that the Court’s authority to check whether the ED has fulfilled the arrest conditions is an added safeguard to this process. The bench wrote that,

“The exercise of the power and satisfaction of the conditions must and should be put to judicial scrutiny and examination, if the arrestee specifically challenges their arrest.”

The bench also pointed out that the legislature has neither expressly or impliedly excluded the Court’s “surveillance and examination of the preconditions” under Section 19. Moreover, the mandatory requirement to produce an arrested person before a Special Court within 24 hours places the Court at the centre of the process.

Justices Khanna and Datta held that judicial review of an arrest is not a “mini trial”, it is only carried out to test whether the investigating agency had sufficient “reasons to believe” that an individual was “guilty” of an offence.

If the investigating officer had recorded the “reasons to believe” in a clear and lucid manner, then “the exercise of power of judicial review would not be a cause of concern.”

“Arrests have to be made on valid grounds and not according to the “whims and fancies of the authorities,” the Court held.

Material that “exonerates” an accused should be given weightage

Kejriwal had argued that co-accused in the liquor scam were released on bail after they were forced to submit implicating statements to the ED. Sarath Reddy, Director of Aurobindo Pharma Limited; Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy and his son Raghav Reddy, who participated in the 2024 Lok Sabha Elections in a party allied to the Bharatiya Janata Party; Buchi Babu; and C. Arvind; former secretary to Manish Sisodia were among the witnesses in the case.

Kejriwal pointed out that the initial statements submitted by the witnesses did not mention his involvement in the case. Bail applications by the co-accused Sarath Reddy and Raghav Reddy were initially heavily contested by the ED. However, after they submitted additional statements mentioning Kejriwal, they were released on bail without any opposition by the ED. The ED responded that “the co-accused were initially reluctant to name and blame the top political stakeholders,” thus, independent witnesses were initially unavailable.

Next, Kejriwal contended that the “material in possession” of the ED to establish the “reasons to believe” did not include “all material” available in the case. Section 19 of the PMLA stipulates “all” and not “some” material must be relied on as grounds of arrest. The judgement held that the ED cannot ignore material which “exonerates” an arrested person.

“They have to equally apply their mind to other material which absolves and exculpates the arrestee,” the Court said.

“The power to arrest under Section 19(1) of the PML Act cannot be exercised as per the whims and fancies of the officer.”

At the stage of judicial review, “reasons to believe” appear sufficient

The Bench refrained from deciding the legality of Kejriwal’s arrest and referred that question to a larger Bench. However, they stated that the ED met the parameters for determining the “reasons to believe” under Section 19.

The ED had submitted that materials collected in their investigation showed that the policy was formulated with the intent to obtain bribes/kickbacks. Further, the ED also recorded that Kejriwal allegedly used the “proceeds of crime” in the Goa Assembly Elections (an amount of ₹45 crores). The Court found these reasons to be sufficient grounds to arrest Kejriwal, particularly because he did not contest these facts in Court. The judgement recorded that,

“During the course of arguments, we had specifically asked the learned counsel appearing for Arvind Kejriwal to address arguments on facts. He did not, however, address arguments on the said aspect.”

The Bench held that if they engaged with Kejriwal’s submissions that the co-accused were coerced into giving statements, they would be entering into the domain of deciding the case based on merits, which they would not do at this stage. In this judgement, they would only consider the legality of arrest. A preliminary review, they said, showed that “subjective satisfaction that Arvind Kejriwal is guilty…is clearly recorded. The allegation of coerced witness statements did not “persuade” the Court to “set aside and quash” the ED’s list of “reasons to believe,” Kejriwal’s involvement. They observed that such arguments were more acceptable while considering Kejriwal’s bail under Section 45 of PMLA.

Was there a “need and necessity” for Kejriwal’s arrest

Kejriwal had argued that the “reasons to believe” submitted by the ED had not mentioned the reasons for the “need and necessity” to arrest him.

The Bench pointed out that substantial parameters to determine this “need and necessity” were not found in Section 19. However, the expression has been given “judicial recognition” in a string of cases in the past.

They wondered whether satisfaction of the parameters under Section 19 were sufficient to arrest an accused, or whether the investigation officer has an added obligation to prove need of arrest. In Vijay Madanlal Choudhary v Union of India (2022), the Court noted that conditions for bail under the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 would also apply on bail under Section 45 of PMLA. Kejriwal argued that a similar logic must apply to arrest under Section 19 of PMLA. He argued that the stipulation in Section 41 of the CrPc that a police officer must be satisfied of the necessity to arrest would apply to Section 19 of the PMLA.

As Vijay Madanlal Choudhary was a three judge Bench decision, Justices Khanna and Datta decided to refer the questions to a larger Bench. The larger bench will decide:

- Whether the “need or necessity of arrest” is a distinct ground to challenge an arrest under Section 19(1) of the PMLA?

- Whether the “need and necessity of arrest” should be subject to the criteria under Section 19 or include personal grounds specific to the “facts and circumstances” of the case?

- What are the parameters and facts to be taken into consideration by a Court when examining the “need and necessity of arrest”?

The legality of Kejriwal’s arrest will be determined after the larger bench settles these questions.

Second time’s the charm: Kejriwal to be released on interim bail

From his arrest on 21 March 2024, Kejriwal was imprisoned in the Delhi Liquor Policy scam for over 90 days. The Bench noted that the “right to life and liberty is sacrosanct,” and as the larger bench will take time to decide the issues, Kejriwal should be released on interim bail. The same same conditions imposed on him when he was released prior to the 2024 Elections in Delhi will apply. The conditions are that:

- Kejriwal cannot visit the office of the Delhi Chief Minister and the Delhi Secretariat

- He cannot sign any official files unless it is necessary for obtaining the clearance or approval of the Lieutenant Governor of Delhi

- He may not make any comments on the Delhi Liquor Policy case

- He is barred from interacting with witnesses and accessing official files connected with the case

The judgement made no directions regarding Kejriwal’s role as the Chief Minister of Delhi. It said,

“While we do not give any direction, since we are doubtful whether the court can direct an elected leader to step down or not function as the Chief Minister or as a Minister, we leave it to Arvind Kejriwal to take a call.”

Kejriwal will remain in judicial custody despite the Court’s grant of interim bail. Moments before a bail hearing in the Supreme Court on 26 June, the Central Bureau of Investigation arrested him in connection to the excise policy case.