Analysis

Ambedkar: The Mooknayak of the disability justice movement

In an essay to mark Dr. Ambedkar’s 135th birthday, V.K. Tiwari suggests that his conception of ‘disability’ could fill constitutional gaps

In a famous exchange between Bombay Presidency Prime Minister B.G. Kher and B.R. Ambedkar, Kher objected to Ambedkar’s assertion that if he had to choose between the depressed classes and the country, “the depressed classes have precedence with him.” Kher had a quarrel with this, “because the part can never be greater than the whole. The whole must contain the part.”

Ambedkar was categorical in his response: “I am not a part of the whole; I am a part apart.”

“A part apart” is a striking phrase. How do you translate it? What image comes to your mind when you attempt to interpret it? Is it an ‘amputated’ part of the society? Bahishkrit Bharat (‘The exiled of India’)? A group rendered “invalid” and humiliated as a “moral menace” by the graded inequality of Hindu society? This is a complex question that cannot be answered so easily. There cannot be one answer either.

Political scientist and editor Gopal Guru once said that every humiliation has its context. I understand Ambedkar’s idea of being “a part apart” in the context of my own physical and cognitive disabilities. ‘Disability’ is the consistent theme in Ambedkar’s works and lifelong struggles. Scholar Upendra Baxi notes that Ambedkar regarded disability, whether physical or mental, as “sociogenic” and highlighted the imposition of “indignity” and “humiliation” as a system that creates a permanent social disability.

Geetha describes caste humiliation as a “bruising” of self-esteem that leaves an “ontological wounding”—a wounding of one’s being. These images of “wounding” and societal amputation as “a part apart” are invariably linked with the disabled figure. Ambedkar’s deployment of this imagery was radical, a way to check societal reality that is based on graded inequality.

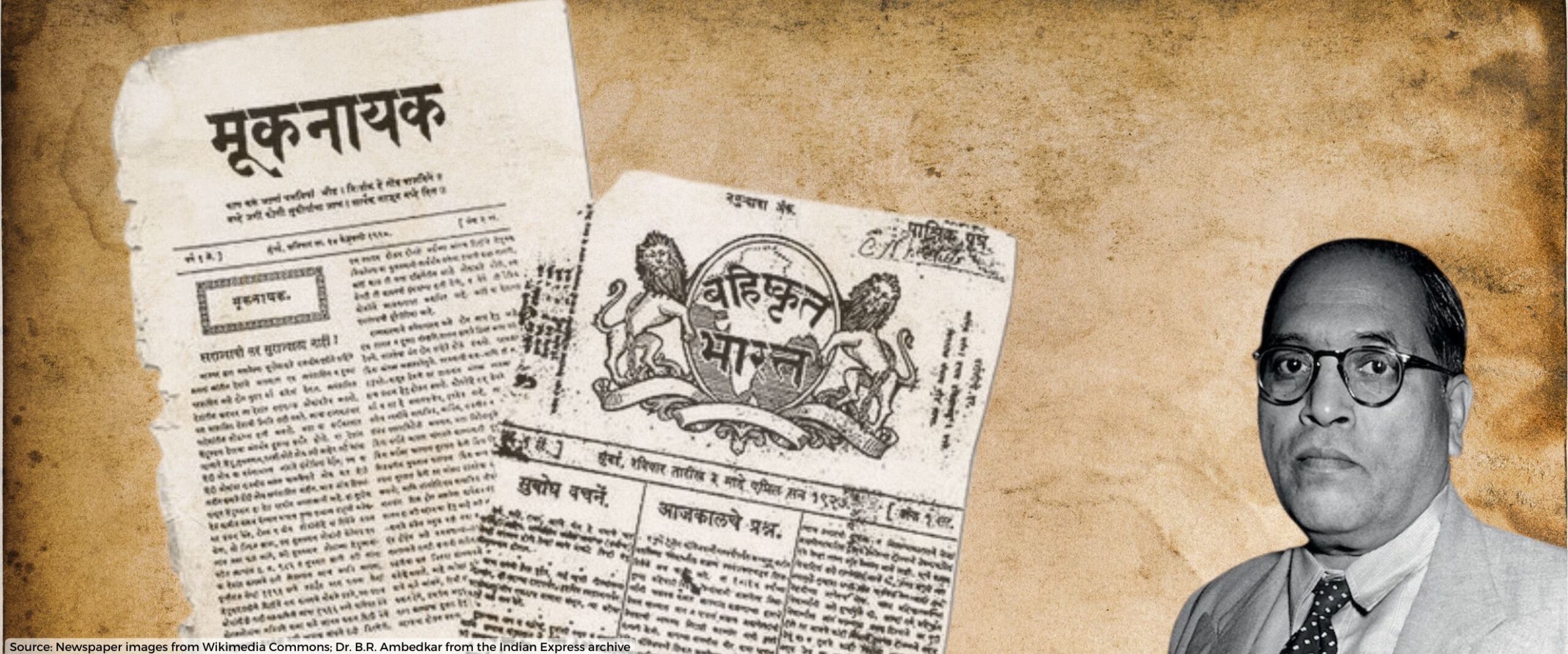

Even in naming his Marathi newspaper Mooknayak, meaning ‘leader of the voiceless,’ Ambedkar used the language of disability to assert the self-respect of the depressed classes.

The ‘Mooknayak’ Ambedkar

Ambedkar’s association with the question of disability is not merely linked with imagery. His struggle was against the debility and disablement of a vast segment of the Hindu society. Deleuze and Guattari, in A Thousand Plateaus, point out that the modern State treats certain bodies as “predisabled, preexisting amputees” who can be disposed of.

The “predisabled” refers to disposable bodies, those that can be sacrificed for the sake of the State. The war, or the accidents of these wars, are mere “optical illusion(s)” that allow the State to transfer the blame for this mutilation onto unfortunate accidents. The mutilation happened a long time ago, when these bodies became predisabled in the “embryo of the world”.

Predisabling of Dalit bodies in the Indian context happens by placing them in dangerous and degrading jobs like manual scavenging. Predisabling happens, if we are to use Ambedkar’s words, by treating them as “shock absorbers in slumps and dead-weights in booms” The mutilation and debilitation of the Dalit bodies in the “embryo of the world” make them vulnerable to the perils of disabilities.

This was Ambedkar’s lived experience too. In his autobiography Waiting for Visa, he narrates a harrowing experience of untouchability in 1929. At the time, Ambedkar was a member of a committee set up by the Bombay Government to investigate the grievances of Dalits. On one of his work travels, he was invited to spend the night in Chalisgaon after investigating an allegation of untouchability in a village “on the Dhulia line”. At the Chalisgoan station, no tongawallas wanted to give him a ride because of his caste. An inexperienced Dalit was sent and the ride resulted in an accident which left Ambedkar with several injuries, including a leg fracture.

The caste system and associated untouchability are the biggest producers of social, physical and other disabilities in India. Ambedkar identified how the Chaturvarnya system had a disabling effect. The caste system, Ambedkar said, “deadens, paralyzes and cripples the people.”

Scholar Valerian Rodrigues views untouchability as a social institution and a “group-bound and life-long disability.” The denial of access is a consistent theme in Dalit and disabled lives and movements, in different but overlapping ways.

Ableism produces a “stigmatized body”, while untouchability does something similar—it dehumanises people and ensures that they “have their persona confiscated.” Dalit and disabled lives are defined and produced as a negative ontology. As Ambedkar put it, “untouchables are nobodies. This makes the Hindus some bodies.” Similarly, as a negative ontology, disability is seen as a “malignancy” and rendered as a “diminished state of being human” by practices of ableism.

Nirmala Erevelles opined that race (read ‘caste’), gender and disability provide the lethal combination of “abjection”. In the Indian context, untouchability and disability represent the most severe abjections of social life. Ambedkar’s formulation of Bahishkrit captures the abjection of stigmatised bodies and communities most authentically. This is one reason every subaltern movement attempts to find its own Ambedkar. Ambedkar as ‘Mooknayak’ would open radical possibilities for the disability justice movement that the dominant strand has not yet explored.

Social model of disability and graded inequality

The social model of disability hinges on removing barriers, especially attitudinal ones and promoting inclusion and accessibility through reasonable accommodation. However, the dominant version of the social model from the Global North does not account for the graded inequality of Hindu society, where caste produces permanent social disability.

Liberal democracies, including India, have developed much jurisprudence on inclusion and reasonable accommodation. But this jurisprudence often fails to rectify the injustices against stigmatised bodies. Can we remove attitudinal barriers through court judgments and liberal laws when society as a whole internalises casteism and ableism as a way of life? How would you accommodate “a part apart” when society lacks fraternity?

Fraternity or sociality played a significant role in Ambedkar’s struggles. Rodrigues observes that, for Ambedkar, “it is sociality which constitutes the human qua human.” Caste makes fraternity impossible for Ambedkar. “As no one is a brother to the other, no one is a keeper of the other,” he said. So, how could the excluded, Bahishkrit, stigmatised, failed bodies seek reasonable accommodation in a society that rendered fraternity impossible?

Moreover, the idea of fraternity as conceptualised in the Indian Constitution doesn’t fully include stigmatised bodies and groups. Professor Farrah Ahmed, drawing on Carole Pateman’s theoretical argument in The Sexual Contract, notes that the constitutional concept of fraternity is gendered, given the thin representation of women in the Constituent Assembly.

Disabled communities had no representation in the Assembly. The testimonial erasure continued later. The Persons with Disabilities Act, 1995, which valorised the medical model of disability, was passed without any discussion in Parliament. The effect of Section 3(3) of the much celebrated The Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016 is that persons with disabilities can be discriminated against if the act or omission in question is a proportionate means of achieving a ‘legitimate aim’. The National Platform for the Rights of the Disabled has consistently opposed this provision.

Abeleism in determining ‘legitimate aim’

If India’s social contract is built on ableism, who gets to decide reasonable accommodation? Who gets to determine the ‘legitimate aim’ to discriminate against the disabled?

I fear the ‘legitimate aim’ test will continue to be informed by graded inequality and ingrained ableism. This concern was borne out in the fact situations of two cases in which the Supreme Court pronounced judgements earlier this year: In re Recruitment of Visually Impaired in Judicial Services and Anmol v Union of India.

Both judgments came down heavily against the denial of access and reasonable accommodation for the disabled in judicial services and medical education, respectively. It’s worth mentioning briefly the facts of the cases to illustrate how casually prejudices are exercised in administrative action.

In the former, the Madhya Pradesh High Court brought a rule that excludes visually impaired and low-vision candidates from judicial services. In Anmol, a disabled candidate, after clearing the NEET examination, was denied admission because a medical officer declared him unfit without providing a reason. Subsequently, the majority opinion of a committee of doctors constituted under the direction of the Supreme Court also declared him unfit, despite lamenting that the Guidelines of the National Medical Commission are obsolete.

In both cases, the question needs to be asked: how are these denials and debarments of the disabled ‘proportionate’? These denials of access, sociality and humanity form the everyday social life of the disabled. The facts of these two cases highlight how ‘legitimate aim’ is often conceived, construed and then executed from an ableist vantage, resulting in a denial of access and fraternity to the disabled.

Reimagining ‘people’ in ‘We the people’

At best, the disabled in India got an ambivalent social contract from the Constitution. The scholar Amita Dhanda wrote that it “neither placed barriers on persons with disabilities, nor protected them against deliberate exclusion.” This ambivalence allowed courts and the government to provide a modular form of citizenship and prescribe a model of disabled being: Divyang. The model is an able-nationalist version in which certain disabled bodies are incorporated into the nationalist narrative while the debilitation of many due to their disability, caste, religion or political opinion can be glossed over.

In Om Rathod v The Director General Of Health Services (2024), the Supreme Court creatively deployed ‘fraternity’ to ensure reasonable accommodation of a disabled student seeking medical admission. But will this ‘fraternity’ be used creatively if a disabled person appears in court as a political prisoner? Is our ‘fraternity’ accommodating enough for a Dalit-disabled body or a Muslim-disabled one?

The answers are inconvenient and discomfiting. After all, liberal tolerance, as scholar Ratna Kapur puts it, “becomes a substitute for justice, where the difference of the ‘Other’ is accommodated rather than her injury redressed.” Progressive legislation and court judgments cannot “quicken the conscience” of society against graded inequality. Inclusion of the excluded, stigmatised, ‘unruly’, ‘ostracised’, Bahishkrit bodies requires a continuous reimagination of the ‘people’ in the phrase ‘We the People of India.’

Ultimately, the project of disability justice in India cannot rest on symbolic inclusion or selective empowerment. The constitutional promise of fraternity remains incomplete when it is conditional and inclusion is granted only to those disabled bodies that conform to nationalist ideals.

True justice demands more than tolerance: it demands recognition, redress and radical imagination. We must move beyond State-sanctioned celebrations and token gestures and listen instead to the voices that disturb, challenge and reframe what it means to belong. It is through these struggles—through our own ‘Mooknayaks’—that the Constitution finds its fullest meaning. From Ambedkar, we learn: the fight for dignity and equality does not begin in the text, it begins in the terrain of resistance.

Vijay K. Tiwari is an assistant professor (law) at the West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences, Kolkata. He can be reached at vijaykt@nujs.edu.