Analysis

5 upcoming Constitution Bench judgements before CJI D.Y. Chandrachud retires

Benches led by CJI Chandrachud are expected to deliver five judgements on matters of minority status, arbitration and public employment

Four working days remain in CJI D.Y. Chandrachud’s two-year tenure as Chief Justice of India. During this time, he heard 16 Constitution Bench cases of nine-, seven- and five-judge benches. This included the challenge to the abrogation of Article 370, the plea for marriage equality and the validity of an unstamped arbitration agreement.

As his tenure comes to an end, five judgements remain.

Can private property be considered “material resources of the community”? | 9-Judge Bench

Over four days in April and a day in May, a nine-judge bench heard arguments on whether “material resources of the community” in Article 39(b) could include privately owned property. It will also decide if Article 31C, introduced through the 25th Constitutional Amendment, of 1971, remains in the Constitution or not.

The case also involves challenges to Chapter VIII-A of the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Act, 1976. Introduced in 1986, this Chapter allowed the Mumbai Building Repair and Reconstruction Board to acquire certain “cessed properties” for restoration purposes with the consent of 70 percent of the residents.

On Day 1, petitioners argued that dilapidated buildings are not “material resources”.On Day 2, the Court stated that it was essential to decide the position of Article 31C. On Day 3, petitioners contended that Article 31C stands inoperative after the Minerva Mills decision. On Day 4, respondents argued that “material resources of the community” cannot be restricted to what is owned by the State. On Day 5, the bench reserved judgement.

Here’s our case docket. Our arguments matrix breaks down the key arguments. Our analysis post discusses how the case brought a crucial constitutional question to the fore—is the original provision of the Constitution revived when an amendment is struck down?

Minority status of Aligarh Muslim University | 7-judge Bench

Over seven days in January and one day in February, a seven-judge bench of the Court heard arguments on whether AMU is eligible to be a minority institution under Article 30 of the Constitution of India. Article 30 states that religious and linguistic minorities have the right to “establish and administer” educational institutions.

In Azeez Basha, a five-judge Constitution Bench held that AMU does not have a minority status. However, Azeez Basha acknowledged that the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental (MAO) College, before it was converted to AMU, was founded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan for the Muslim community.

After Azeez Basha, Parliament passed the Aligarh Muslim University (Amendment) Act, 1981 which stated that AMU was “established by the Muslims of India.” In 2005, the Allahabad High Court struck down the 1981 amendment for being inconsistent with Azeez Basha.

On Day 1, petitioners argued that the existence of a central legislation was not a bar to AMU’s minority status. On Day 2, petitioners argued that the purpose of minority institutions is to impart quality education. On Day 3, petitioners contended that AMU was responsible for the educated Muslim middle class. On Day 4, the Union contended that AMU voluntarily relinquished its minority status to the British government. On Day 5, Union argued that AMU was primarily a non-minority institution. On Day 6, respondents argued that minority rights did not exist before the Constitution. On Day 7, respondents contended that AMU was constitutionally recognised as a non-communal institution. On Day 8, the bench reserved judgement

Here’s our case docket. Our arguments matrix breaks down the points put forward by various parties. We’ve explained the case in video here. Our analysis post discusses how the AMU Act has to be read as a key way-stop on the continuum of the institution’s history, not as something that breaks with it.

Appointment of arbitrators by ineligible persons | 5 Judge Bench

In 2019, in Central Organisation for Railway Electrification (CORE) v M/s ECI-SPIC-SMO-MCML (JV) a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court set aside the Allahabad High Court’s appointment of an arbitrator, stating that it had to be done as per the General Conditions of Contract (GCC) between the two parties.

The GCC allowed CORE, the appellant, to nominate a panel of four people, from whom the respondents could pick two out of the three arbitrators to form a tribunal. The third person would be picked by the General Manager of CORE, who is ineligible to be an arbitrator himself according to Section 12(5) of the Arbitration Act. The three-judge bench had noted that since the “respondent has been given the power to select two names from out of the four names of the panel, the power of the appellant nominating its arbitrator gets counter-balanced by the power of choice given to the respondent”.

As a five-judge bench heard the matter over three days in August, two questions emerged before the bench: First, whether a person who cannot be an arbitrator can appoint one. Second, whether it is permissible for the panel of arbitrators to be nominated unilaterally.

On Day 1, private contractors argued against the unilateral appointments and nominations of arbitrators. On Day 2, the Union argued that the unilateral appointment of a panel was permissible if there was a prior agreement on it between the parties. On Day 3, shortly after non-banking financial companies and other intervenors made submissions, the Court reserved judgement

Here’s our case docket. Find the full argument transcripts for Day 1, 2, and 3.

Validity of ‘Light Motor Vehicle’ Licence to Drive ‘Transport Vehicle’ | 5 Judge Bench

Over seven days, from July 2023 to August 2024, a five-judge bench of the Court heard arguments on whether a person licenced to drive a ‘light motor vehicle’ under the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 is automatically entitled to drive a ‘Transport Vehicle of Light Motor Vehicle Class’ with an unladen weight of less than 7500 kg.

In March 2022, the appellants, Bajaj Allianz General Insurance argued that the Supreme Court’s 2017 decision in Mukund Dewangan erred in allowing holders of the light motor vehicle licence to drive a transport vehicle. On March 8th 2022, a three-judge Bench referred the case to a larger bench to review the points omitted by the Court in Mukund Dewangan.

On Day 1, petitioners took the Court through the various provisions of the MVA that create a distinction between Light Motor Vehicles and Transport Vehicles. On Day 2, petitioners argued against allowing standard licence holders to drive transport vehicles, raising concerns about safety. On Day 4, the Union explained why they had introduced notifications in 2018 and 2021 and amendments to the Central Motor Vehicles Rules, 1989. On Day 5, the Union sought an adjournment of the case, which was declined. On Day 6, the Union placed on record a note on the consultative process undertaken between the Union and all the stakeholders in the case. On Day 7, the Court reserved judgement.

Here’s our case docket.

Altering Rules on Appointment to Public Posts | 5-judge Bench

On September 17, 2009, the Rajasthan High Court issued a notification under the Rajasthan High Court Staff Service Rules, 2002 (the Rules) for the recruitment of 13 translators. The Rules required candidates to appear for a written examination and a personal interview. However, after the completion of these two steps, then Chief Justice of the Rajasthan HC Jagadish Bhalla, decided that candidates must receive 75% or above in their examination to be selected for the post. As a result, only three of the 21 candidates were selected.

Unsuccessful candidates approached the Supreme Court in 2011 arguing that ‘changing the rules of the game after the game was played’ was impermissible and violated their right to equality and non-discrimination under Article 14 of the Constitution. The judgement will affect public appointments across various states.

On Day 1, the Court heard the batch of petitions pertaining to the Kerala HC. It also heard the petitions on Manipur HC. On Day 2, they heard and de-tagged petitions from Gujarat, Gauhati, Patna and Rajasthan. On Day 3, the bench reserved judgement.

Here’s our case docket.

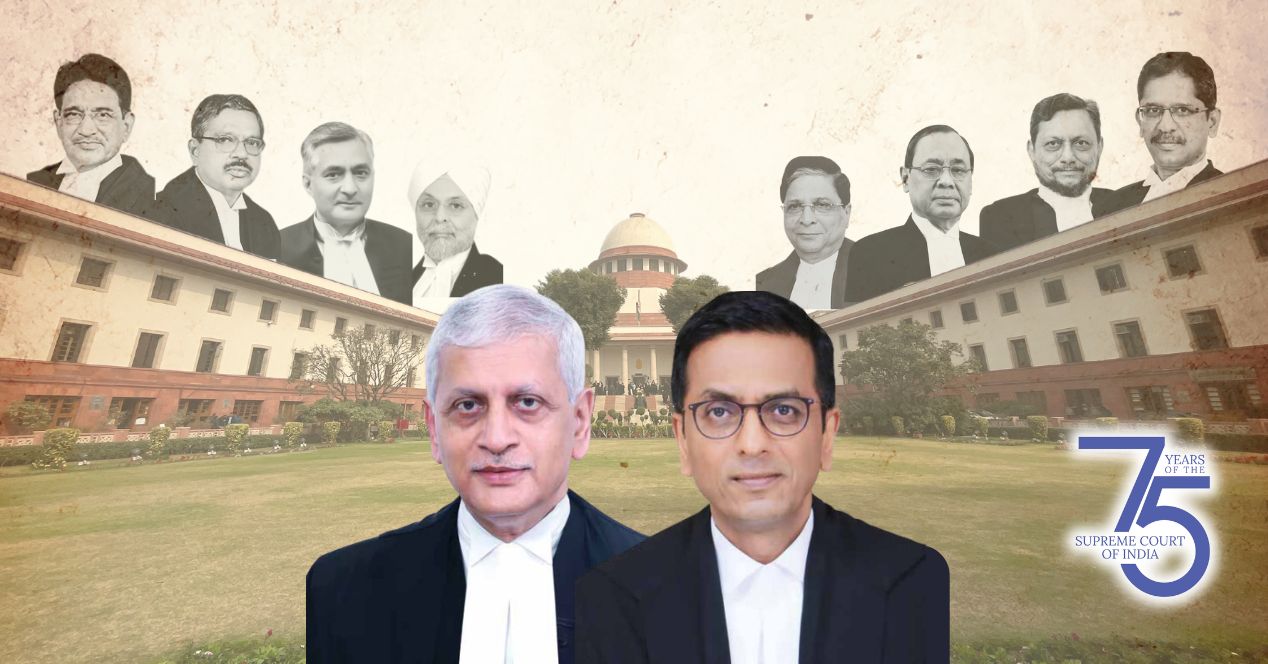

What lies ahead for Justice Khanna

Justice Sanjiv Khanna will assume office as India’s 51st Chief Justice on 11 November 2024. He will head the Supreme Court as Chief for six months.

On the Court’s docket during his term, are crucial cases like the challenges to the marital rape exception, the Bihar caste census and the Sabarimala review. The Khanna-led collegium is also expected to elevate four new judges to the Supreme Court. Lingering institutional cases, such as the controversy surrounding listing will also remain challenges.

From his predecessor CJI D.Y. Chandrachud, who retires on 10 November, Justice Khanna will inherit a technologically revamped Court, but the Khanna Court will have to deal with a high pendency of over 82,000 cases. Here’s everything Justice Khanna will likely have in store.