Analysis

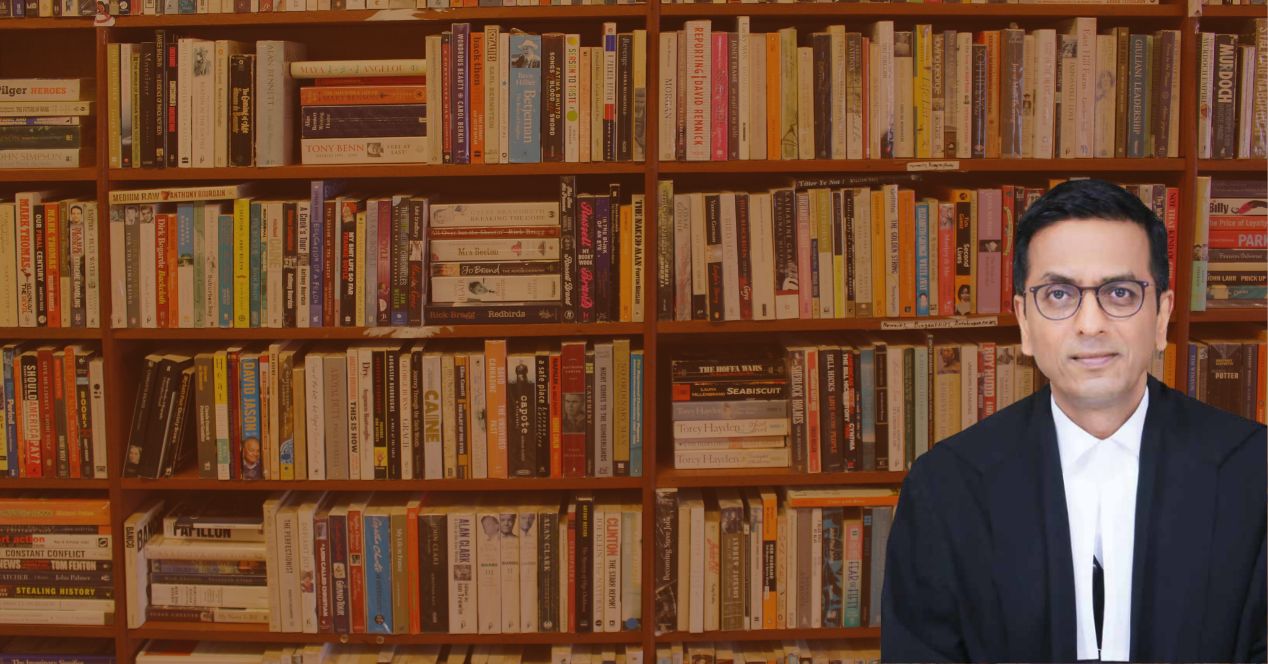

36th LAWASIA Conference 2023 | Identity, the Individual and the State: New Paths to Liberty | Chief Justice D. Y. Chandrachud

In his keynote address at the LAWASIA Conference 2023, the Chief Justice spoke about identity, liberty and the fight against discrimination.

TRANSCRIPT

My very distinguished colleagues Sanjay Kaul, the Chief Justice of the Karnataka High Court, Justice Prasanna Varale, Mr. Shyam Divan, Mr. SS Naganand, Mr Amarjit Singh Chandiok, distinguished judges, lawyers, and guests, let me begin on a personal note.

As we move into the discussions of the 36th session of Law Asia, we must pause for a moment and think of those who have mentored this organization and I’d like to reflect particularly on Shyam’s very distinguished father Mr. Anil Divan who has mentored these global institutions. They have contributed to an international judicial dialogue and perhaps more significantly, in pitchforking the Indian legal profession as one of the active participants in the global arena. I would also like to tell you a little bit about my own association though virtually, with Rukmini Vijayakumar. In the time of isolation during COVID, I followed Rukmini’s performances very avidly and her dance form to my mind represents a quest for fitness based on yoga, and a blend of spirituality and form which have inspired me personally to lead a more holistic and rooted existence. So thank you very much Rukmini.

I would like to start by congratulating Law Asia for building such a robust alliance of the legal fraternity in the Asia Pacific region. In a world more interconnected than ever these associations help us find meaningful partnerships, strategies and avenues to share ideas and cultures. But the theme of this conference which is “Everything, Everywhere, All At Once: Lawyering in the Digital Age” is fascinating. In the Oscar-winning movie which is the namesake of this conference, we see a middle-aged Chinese-American immigrant who is confronted by multiple struggles like bankruptcy, accepting her daughter’s queer relationship, running a business, taking care of her ailing father and keeping her marriage intact. She gets in touch with her versions from parallel universes in which she made different choices and flourished. The protagonist jumps across the multiverse acquiring skills from various realities, becoming an amalgam of seemingly irreconcilable selves which reveal themselves to be inexplicably linked. The underlying message there is that we are not singular beings but we rather contain a multitude of versions; We are everything, everywhere, all at once. But at the same time, we are nowhere, we are not rooted in, nor do we belong in one place. We crisscross worlds and often even cultures and that I do believe is the true message of the Law Asia movement.

I’ve been asked to speak on the topic of identity, the individual, and the state: new paths to liberty.

First, I will talk about the historical context in which liberty was understood. Second, I will talk about the limitations of this understanding and the inclusion of identity and the state within the fold of liberty. Lastly, I will talk about the regimentation of identity and its reimagination as a path of liberty.

The ability to make choices for oneself and change our cause of life is called liberty. Identity intersects with a person’s agency and life choices. As lawyers, we are constantly confronted with this intersection and the role of the state to limit or expand the life opportunities of people. While the relationship between the state and liberty has been understood widely, the task of establishing and explaining the relationship between identity and liberty is incomplete. Traditionally, liberty has been understood as the absence of state interference in a person’s right to make choices. However contemporary scholars have come to the conclusion that the role of the state in perpetuating social prejudices and hierarchies cannot be ignored. In effect, whether the state does not intervene, it automatically allows communities with social and economic capital to exercise dominance over communities who have been historically marginalized.

From the era of Enlightenment to the struggles for Independence from colonial regimes, liberty was primarily perceived as a freedom from external constraints which is the liberty of the individual to act without interference from tyrannical rule. It was a vision rooted in the autonomy of the singular self, a narrative of personal freedom that resonated with the spirit of resolutions, (and) revolutions across the globe. John Stuart Mill, in his book on liberty published in 1859, discussed the historical struggle between authority and liberty, describing the tyranny of government, which in his view, needs to be controlled by the liberty of the citizens.

Mill divides this control of authority into two mechanisms.

Firstly, necessary rights belonging to citizens, and secondly, that there must be constitutional checks for the community to consent to important acts of the governing power. The idea of liberty as personifying unregulated freedom can be summarized in the phrase that “your right to swing your fist ends where my nose begins.” This form of liberty champions individual rights but is agnostic to identity, because it allows the free exercise of options by individuals without state interference. Yet, as we navigate the currents of time, it becomes imperative to acknowledge the limitations of this historical understanding of liberty.

To understand traditional liberty, imagine that each of you is driving a car and you come to a fork in the road. You turn left, but no one is forcing you to go one way or the other, so you seem as a driver to be completely free. Therefore, the driver wouldn’t have complete liberty in the traditional sense, but this picture of your situation might change quite dramatically if we consider that the reason you went left is that you’re addicted to cigarettes and you are desperate to get to the local paan shop or the local 911 to buy a packet of cigarettes. You long to be free of this irrational desire that is not only threatening your longevity but is also stopping you right now from doing what you think you ought to be doing. Here, liberty would mean that you must have agency over your actions to decide what is best for you.

The individual, though a crucial player, is not an island unto themselves. Identity woven intricately into the fabric of our existence cannot be divorced from the discourse on liberty. It fails to take into account that individuals do not have equal agency to exercise their freedoms with or without state interference.

Therefore, people who face marginalization because of their caste, race, religion, gender, or sexual orientation will always face oppression in a traditional liberal paradigm.

This traditional, liberal paradigm empowers the socially dominant in two ways. First, it removes state fetters from them to act as they please. Second, it emboldens dominant social groups to exercise their existing dominance to oppress marginalized populations.

The state, often viewed as a potential threat to individual freedom, has now been re-examined within the broader scope of liberty. Social movements throughout history have pointed out the inherent hypocrisy in the claim that liberty is agnostic to identity, by pointing out that systemic social discrimination is so embedded in the system that is often assumed to reflect the natural order of things, that the natural order in which negative liberty is presumed to operate is actually an economically affluent upper caste cisgender heterosexual male perspective, is actually an economically dominant perspective today. Identity and its recognition by the state play the crucial part in what resources people get and their ability to express their grievances and demand better rights. The State therefore confers personhood and juristic personality as a first step in recognizing the claims of entities and individuals.

In our digital age we are now faced with several fascinating aspects of artificial intelligence. There is a complex interplay between artificial intelligence, AI, and personhood where we find ourselves navigating uncharted territories that demand both philosophical reflection and practical considerations. In contemplating the intersection of AI and personhood, we are confronted with fundamental questions about the ethical treatment of these technologies. This scenario evokes reflections on Sophia, a humanoid robot as an example that had captured the public’s attention. Sophia can engage in conversations, express emotions through facial expressions and was even granted citizenship in Saudi Arabia. While a humanoid robot was granted citizenship, we must reflect whether all humans who live, breathe, and walk were entitled to personhood and citizenship based on their identity.

History is replete with examples of state prejudice based on identity. In this context, it made sense for social movements to demand that their identity be treated with respectability and create better conditions for the exercise of liberty. For example, laws framed around the gender binary, have historically led to the concentration of wealth in the hands of men. These laws commit a dual fallacy: first, we assume that there are two and only two genders that must be distinguished. Second, they actively disadvantaged women and advantage men. These laws should look like seemingly neutral criteria of lifting, for example, three times the body weight of a person for the selection of a firefighter. Not only is this criteria unrelated to the job of a firefighter, but it invisibilises the anatomical differences between different sexes, thereby restricting the employment and economic opportunities of firefighters only to men.

The Supreme Court of India in Anuj Gar v Hotel Association of India, was faced with a challenge to Section 30 of the Punjab Excise Act, which prohibited the employment of any woman in any part of an establishment in which liquor or any other intoxicating drug were consumed. Our court in striking down this patently discriminatory provision held that a sex-based classification cannot be justified on the basis of a blanket assertion of natural differences between men and women under the anti-stereotyping principle. In the Secretary, Ministry of Defence v Babita Puniya, which was delivered just on the anvil of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, The Supreme Court rejected the notion that a woman is the weaker or inferior sex, and in doing so, it held that arguments founded on the physical strengths and weaknesses of men and women and on assumptions about women in the social context of marriage and family do not constitute a constitutionally valid basis for denying equal opportunity for women officers in the Indian armed forces, and therefore today we have women at the forefront of our borders; they are in the high seas manning our naval vessels, and they are fighter pilots in the Indian Air Force. These cases show how identity has been used as an assertion for guarantees against discrimination by the State. Because there is discrimination based on people’s identity, we see resistance also centered in the vocabulary of identity.

Another notable dimension is the intersection of climate, tribal rights, and challenges stemming from rigid identity impositions. As a scholar, Talal Asad points out the responsibility for safeguarding human rights is often placed in the hands of individual sovereign states, whose jurisdiction is bounded by national economies. This framework unfortunately fails to address harms perpetrated on one’s country’s economy by another, even if it inflicts irreparable damage and suffering on a large scale, as it does not constitute a violation of human rights of those who are affected. In this context, we must acknowledge the inherent complexities within the culture of law, which is saturated with power imbalances. The human rights culture, far from being a transcendent language of justice, often articulates inequalities which are embedded in social life.

This then raises the question: Is the discourse on human rights the sole language through which we can articulate justice?

To extricate human rights discourses from entanglements in webs of subjugation and disentitlement, we must broaden our perspective. The notion of popular sovereignty, for example, inherently demands the inclusion of pluralism and diversity at its core. An explanation of the struggle for survival and dignity by constitutional collectivities such as our Scheduled Tribes in India underscores the imperative of imagining life-worlds of freedom and dignity. For tribal or the Adivasi communities, the right to liberty finds expression in territoriality, homelands that confer a particular identity and enable distinct livelihood practices, their struggles, particularly around issues of forest rights, governance, autonomy, and self-determination, exemplify the embodiment of autonomy and sovereignty encapsulated in the tribal or Adivasi slogan “Mava Nate Mava Raj”- Our land, our rule.

These and many such assertions of identity in the face of discrimination have provoked two trends globally: one of affirmative action and the other of understanding multiple identities through an intersectional analysis.

In India, affirmative action has been prescribed, even mandated by the Constitution in the context of the scheduled castes, the scheduled tribes, and the backward classes. Caste, far from being a vestige of the past, continues to exert significant influence on contemporary socio-economic and political landscapes. Its resilience is evident in the social stratification, economic disparities, and access to opportunities experienced by different caste groups. I would like to note that caste dynamics in the region are not exclusively shaped by religious affiliations. The intricate caste system is not merely a response to historical inequality, but functions as a potent tool for disrupting entrenched societal structures. Many reports in India, such as the Sachar Committee Report and the Justice Ranganath Committee Report, have brought attention to the widespread abuses which are faced by marginalized communities, including social segregation, untouchability, limited access to education, and underrepresentation. These findings underscore the pressing need for affirmative action to address deeply-rooted discrimination. Within this complex tapestry, affirmative action emerges as a transformative force challenging established caste dynamics. It goes beyond the misconception of caste as a solely cultural phenomenon and serves as a catalyst for change.

I remember that one of my predecessors, Chief Justice Sharad Bobde, recognised the necessity to consider the social exclusion of Christians and Muslims from the Scheduled Caste, reinforcing the urgency of addressing these issues. The argument unfolds cohesively, illustrating how affirmative action acts as a beacon of hope, working to dismantle age-old caste-based inequalities and paving the way for a more equitable future. Implicit in our conversation around identity is our assumption that people hold one identity at a time. How untrue!

Identity and its conversations have thus embraced the tendency of becoming the domain of the oppressed because the identity of socioeconomically advanced segments have already been translated into material capital. Not only does this attach a trope against those pointing out tangible ways in which society is prejudicial to communities, but it also does injustice to those upon whom multiple vectors of identity operate to create unique patterns of marginalization globally.

Scholars like the very distinguished Kimberle Crenshaw have analysed the theory of intersectionality. Other feminist critics, like Bell Hooks, prefer not to use the term intersectionality. According to Bell Hooks, the society as it exists itself is rooted in the identities of the privileged. She prefers to use the more elaborate terms of “white supremacist”, “imperialist”, “capitalist”, and “patriarchy” to highlight the knitting together of identities that have led to the maldistribution of liberty in our contemporary world.

This is not just an academic discourse; it’s a real-world issue affecting lives across the globe. Let me tell you by delving into the intricate landscape of intersectionality for a brief moment. A very distinguished Indian scholar, Nivedita Menon, and another scholar, Rita Dhamoon, have astutely critiqued the concept of intersectionality, while a powerful analytical tool, faces challenges in its application. I have applied intersectionality myself in several of my judgments. The theorisation of multiple and interlocking vectors of identity have led us to question its efficacy in diverse contexts. As Menon contends, it undermines traditional forms of patriarchy but risks being de-politicised, leading to an ornamental intersectionality.

We must then navigate the tensions between discipline feminism, the commodification of analytical categories, and the risk of superficial challenges to existing power structures.

So then what is our path forward with intersectionality? Despite these critiques, we must view it as a powerful mechanism for unravelling the simultaneity of subjugations and building coalitions across different marginalities.

It is all about recognising the interlocking systems of power that shape our lives. Identity has been portrayed as an essential, inherent component of the self. While no doubt the effect of unfair distribution of life opportunities based on identity are very real. But the distinction based on identity was created to serve no useful purpose. And I said an assertion based on identity, is a natural and valid response to the identity-obsessed world in which we live. However, it has reified the false distinction between people based on their identity. Knowledge in this case is always partial and contextual. What we know is only ever a part of the picture, and it is based on who, where, and when we are. Knowledge cannot be neutral or objective.

No knowledge is ideologically neutral. Knowledge is contingent on systems of power, and it shapes the power relations between people. In the course of understanding identity, the individual and the state, we see our own transforming understanding of liberty. Whereas the traditional understanding of liberty falsely claimed it to be agnostic to identity, the new age understanding is not without its demerits. In our well-founded assertions of identity, we must not forget that removal of the underlying systemic discrimination would require us to abandon the notion that people must be categorised into boxes. Boxing of people into rigid identities is one way in which society may deprive communities and individuals from exercising their freedoms. As a queer feminist scholar Gayle Rubin’s work highlights, there are dangers inherent in identity-based assertions. We can fight to get our group into the ‘charmed circle.’ But other groups further down the line will continue to be marginalised, pathologised and criminalised, often those who are already the most oppressed.

The boxing of people into rigid identities is also a by-product of over-identification. For example, the division of people with disability to afford state benefits instead of making accessible infrastructure and disability-friendly education and employment sectors. People with disabilities are forced to get a certificate for entitlements under the Right of Persons with Disabilities Act of 2016. This has led to the problem of creating a benchmark for disability to avail of state benefits.

This has led to: first, many disabled people falling through the cracks because they cannot be boxed into a benchmark scale; second, it has distracted from the larger solution of fixing our overall physical infrastructure; and third, persons with disabilities are still relegated to an inferior status in need of state rescue because it is taken for granted that they are an exception to normal and will require special accommodation. We need not look any further to understand an alternative world where we are able to move beyond our need for over-identification than to see the example of persons who wear eyeglasses. People like me who wear glasses are not considered persons with disabilities because eyeglasses have been made widely available. The stigma against people with specs is non-existent, and no practical difference exists in the distribution of life chances between people with or without eyeglasses.

Therefore, as I wrap up, may I say, while the journey of liberty has aimed to maximise human freedoms, it is our life’s work to imagine liberty as the removal of systemic barriers and make oppression-based identities obsolete. This is not to say that persons with certain identities will be invisibilised; however, the stigma and the difference attached to them would become part of a benign distinction; one of several that humanity cherishes even today.

I thank you very much for inviting me to share my thoughts with you, and I wish the deliberations over the period of this conference the very best from the bottom of my heart. Thank you very much. Namaste.