Analysis

Suo Moto Powers in Writ Jurisdictions: A South Asian Innovation?

The Indian Courts seem to have pioneered the use of suo moto powers, inspiring other South Asian Courts, including Pakistan and Bangladesh.

Since January 2020, the Court has taken up 13 cases ‘suo moto’. This means they take up cases by their own notice, without any petition being filed, or interest being brought before them. These cases have included some of the most important ones during the pandemic, dealing with prisoners, migrant workers, vulnerable children and vaccine policy.

Such a ‘suo moto’ power is granted by S. 23 of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971 in regards to contempt of court. Many other common law jurisdictions give Courts this power. However, the use of the procedure in writ or judicial review jurisdiction has been novel to India, where it is used to scrutinise or test executive (in)action.

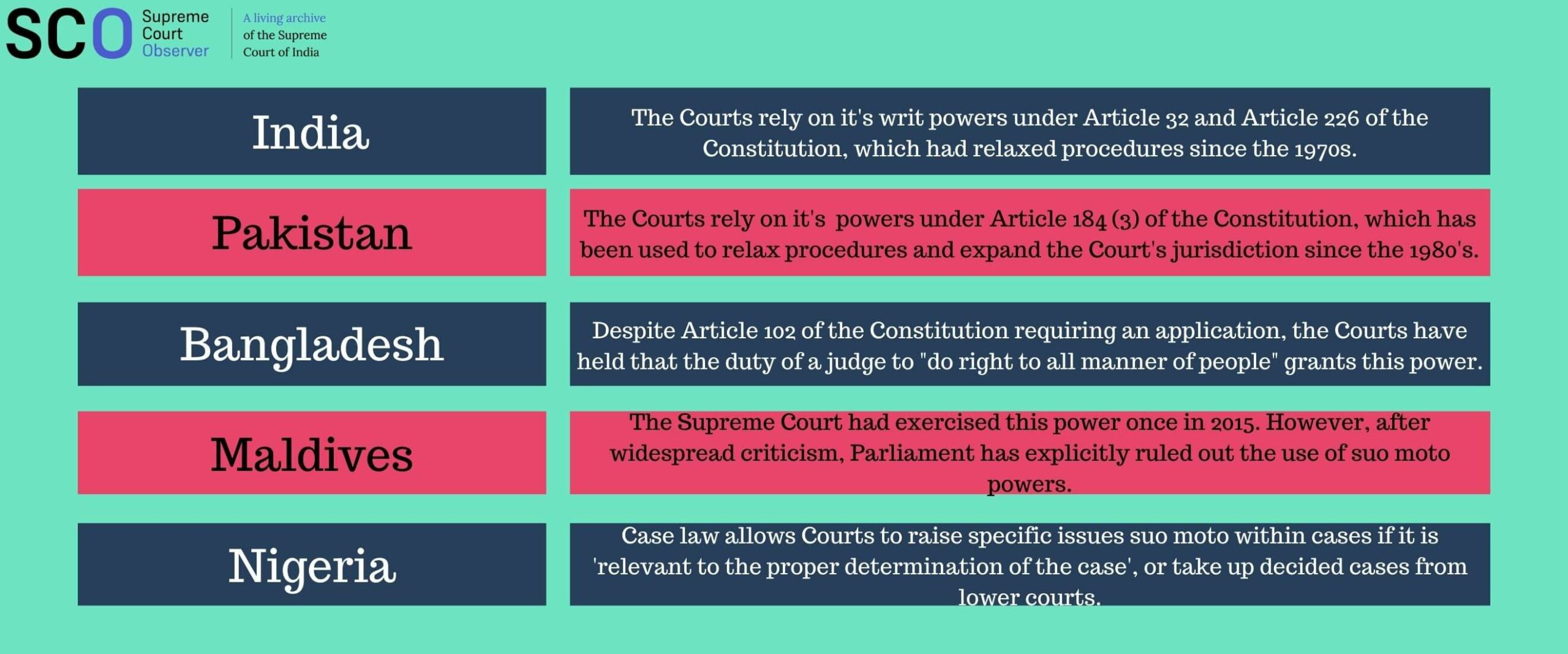

Marc Galanter and Vasujith Ram note that it developed from the relaxation of procedure when considering public interest litigations. The Courts have justified this power under Articles 32 and 226 of the Constitution of India, 1950.

One of the earliest uses of the suo moto procedure was in the Gujarat High Court case by Judge MP Thakkar (Special Civil Application 2785/79) in 1979. The Court took notice of a news article of a wife not being paid pension from the PPF after the death of her husband. The Court ordered the State to grant her pension.

At the Supreme Court, in the Sunil Batra case in 1980, a letter was taken up as a petition. This practice of treating informal letters as petitions has been called the Court’s ‘epistolary jurisdiction’ by academics. Suo moto cases have been taken up by the initiative of the judge(s) themselves, in a similar vein. In 2014, the procedure for suo moto petitions at the Supreme Court was formalised by the adoption of Order 38, Rule 12(1)(a) in the Supreme Court Rules, 2013.

Older jurisdictions such as the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada have not taken up such powers. Administrative and constitutional law cases in these jurisdictions remain within the traditional adversarial procedure, where a petition must be filed before a claim can be considered. In Carlisle v. United States, the Supreme Court of the United States held that the Court could not move ‘suo moto’ in order to grant an acquittal.

The Indian Courts seem to have pioneered this unique use of suo moto powers. It has inspired other South Asian Courts to take up similar suo moto cases. The most common use outside of India is seen in Pakistan. The Court has relied on Article 184(3) of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973 to justify their suo moto power. This Article allows them to correct violations of fundamental rights, which was used commonly in the 1980’s when martial law was lifted.

This procedure has been used more often in recent times. Under CJP Nisar (2016-2019), the Supreme Court of Pakistan initiated at least seven suo moto cases. During the COVID pandemic, various Pakistani courts have initiated cases to deal with the fallout of the pandemic, like in India.

A Bangladeshi Court first used the procedure in 1992, to quash the conviction of a prisoner who had been jailed for 12 years since the age of nine. Courts have since used what they call the ‘Suo Moto Rule’ for various purposes, although more sparingly than the Indian and Pakistani Courts. Besides cases quashing criminal convictions, some other cases include intervening in ‘local arbitration’ over a child rape and who can issue fatwas.

In 2015, the Supreme Court of Maldives had issued an order against the Human Rights Commission of Maldives in a suo moto case. The guidelines in the order restricted the Commission’s powers and its ability to interact with foreign bodies. After criticism, the Parliament passed a law to explicitly restrict the power.

Even beyond South Asia, the Nigerian Courts have exercised suo moto powers in a unique manner. However, this is usually by raising a particular issue suo moto within an existing case, or taking up a case decided in a lower court before an appeal is filed.