Analysis

The Sedition Order: A Real Hope for Free Speech?

DESK BRIEF: The intended impact of the SC's relatively ambiguous Order remains unclear.

On May 11th 2022, a three-Judge Bench consisting of Chief Justice of India N.V. Ramana and Justices Surya Kant and Hima Kohli delivered an unexpected Order on the constitutionality of sedition.

In an affidavit filed earlier this week, the Union government said it will ‘re-examine’ the constitutionality of Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Deferring the hearings until the re-examination is completed, the Order ‘hoped’ and ‘expected’ that no coercive action will be taken by State and Union law enforcement agencies under S 124A in the meanwhile. Investigations and hearings in existing cases under S 124A have been paused until the next hearing in July.

The Bench’s concerns with the rampant misuse of S 124A have been clear since the beginning of the hearings. However, its optimism that the police and Executive will fall in line with its ‘hopes’ belies the labyrinthine realities of criminal procedure in India. Even judgments that clearly declare laws unconstitutional take time to trickle down. And so, the intended impact of this relatively ambiguous Order remains unclear.

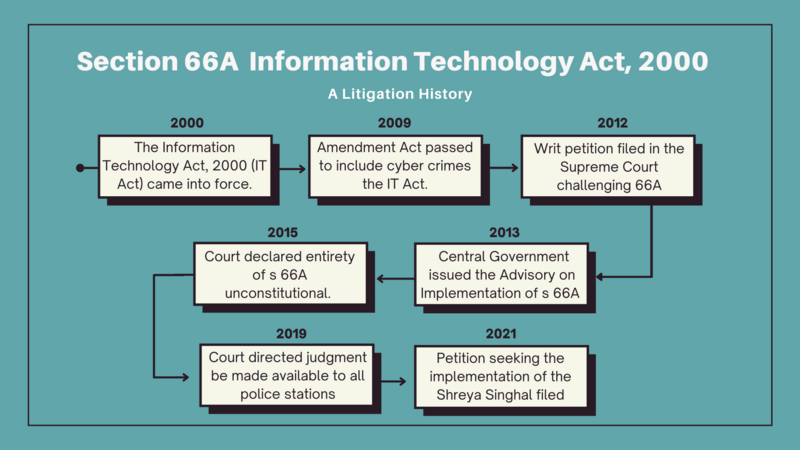

For example, in Shreya Singhal v Union of India (2015), the SC unambiguously struck down Section 66A of the Information and Technology Act, 2000, which criminalised transmitting ‘grossly offensive’ material online. As of 2021, police officers all over the country had continued to register 1,307 cases under the dead provision.

Whether yesterday’s Order, which falls short of a clear stay on S 124A, will engender similar outcomes remains to be seen. Will police officers who continue to use S 124A be held in contempt of Court? How long will those newly accused under S 124A have to wait in custody before a Court hears their case and quashes the FIR against them?

The Supreme Court’s quick acceptance of the Union’s re-examination request demands equal attention. Hearings are rarely deferred because the Executive expresses an intention to re-examine the challenged law. As the petitioners noted, similar requests for deferral were rejected in the Right to Privacy hearings at the SC and, more recently, in the marital rape hearings at the Delhi High Court. The end result of re-examination, in this case, is uncertain. Will the Union repeal the law or regulate its use? The Union’s earlier affidavit states that the provision is constitutional and guidelines are enough to prevent misuse, indicating that regulation is likely.

For now, the Order offers qualified hope—those held in police custody under the sole charge of S 124A are likely to be granted bail. The arrest of a journalist booked under sedition was stayed by the Rajasthan High Court mere hours after the SC’s Order. However, for the likes of sedition-accused Sharjeel Imam and Umar Khalid, charged as they are under a gamut of criminal laws including the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, the future is not as bright.

While it appears inevitable that the Court will be called upon to rule on S 124A again, this is unlikely to happen before Ramana CJI’s retirement in August 2022. The CJI has lamented the colonial legacy and misuse of sedition law before. Yesterday’s Order may mark one of his last attempts at shaping a law he has past critiqued.