Analysis

The ‘first woman’ problem

A century after winning the right to practice law, women in the highest ranks of the judiciary remain the exception, not the norm

In 1892, Cornelia Sorabji from India became the first woman to pass the Civil Law examinations at Oxford. Despite passing the Bar, she was not allowed to plead before the Allahabad High Court as the profession was restricted to men at the time. Twenty four years later, not much had changed. In 1916, Regina Guha’s enrollment application was rejected by a bench of five judges of the Calcutta High Court. “As law stands, a woman cannot be enrolled as a Pleader,” the judges wrote.

Legal practice back then was governed by the Legal Practitioners Act, 1879. Section 5 of the Act stated: “No person shall appear, plead or act as a pleader… unless he shall have been admitted and enrolled…” While the law never explicitly barred women, the assumption at the time was that the “he” in this law was literal, not indicative.

Around this time, a larger movement for women’s rights in the legal profession was gaining momentum in India. In 1923, Dr. Hari Singh Gaur, a legislator, moved the Central Legislative Assembly to amend the 1879 Act. This kickstarted a series of events, culminating in the enactment of the Legal Practitioners (Women) Act, 1923. Finally, women could practice law in India. Sorabji then became the first woman to become a vakil in the country.

Since then, more women have followed. Anna Chandy became India’s first woman judge in 1937. In 1944, Violet Alva was the first woman advocate to argue before a full High Court bench. In 1959, Chandy became only the second woman in the world to become a High Court Judge.

It took another 30 years for the Supreme Court to see its first woman judge. Justice Fathima Beevi assumed office on 6 October 1989. “I opened a closed door,” Justice Beevi said in an interview while also remarking that there was no “scarcity” of competent women in India. The fact, however, is that very few women have walked through that door. In the 35 years since, the top court has seen only 10 other women judges.

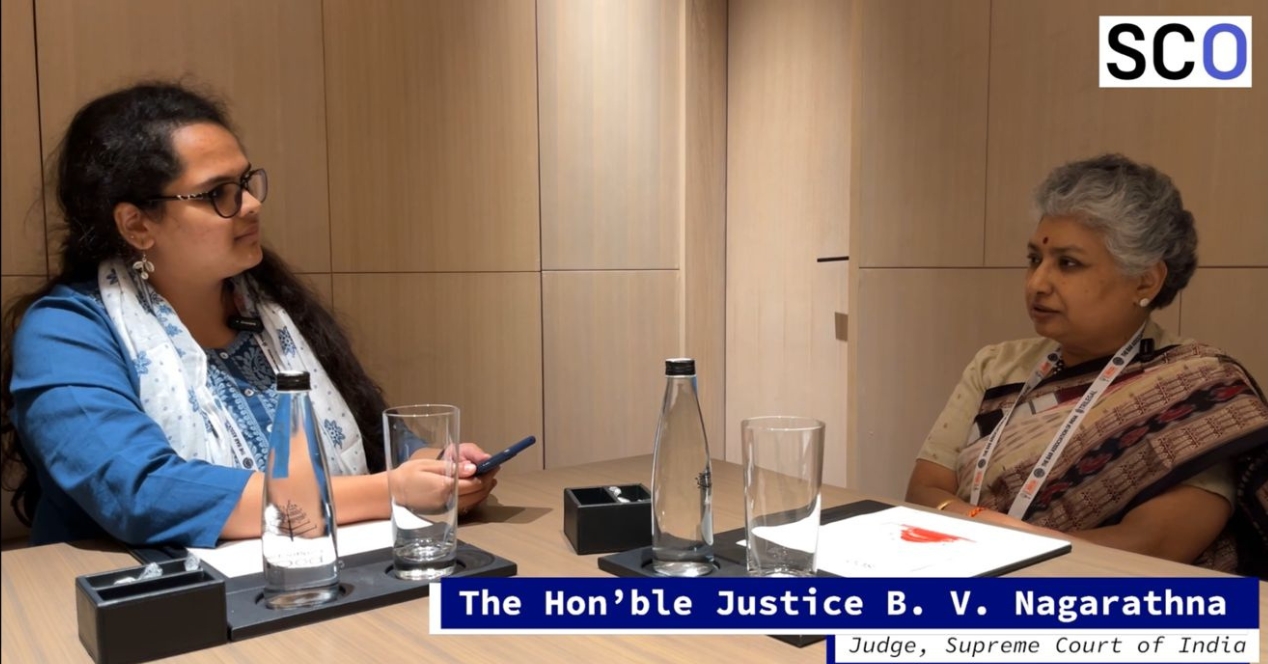

The year 2021 stood out, for it saw the highest number of women judges in the Supreme Court. Justices Hima Kohli, B.V. Nagarathna, and Bela M. Trivedi were elevated together and joined Justice Indira Banerjee. This cohort also laid the foundation for India’s first woman Chief Justice. If the seniority principle is followed, Justice Nagarathna will assume office as CJI in 2027.

Undoubtedly, there are more women in the legal field today. As of 2023, there were 28,4507 women advocates, according to data collected by the Bar Councils of 15 states. However, this accounts for only 15 percent of the total number of advocates in India.

Gender representation continues to be an issue on the Bench as well. According to data published by the Supreme Court in 2023, 36.3 percent of the officers in the district judiciary and only 14 percent of judges in High Courts were women. Currently, only two out of the 32 sitting judges in the Supreme Court are women.

Milestones matter. However, celebrating “firsts” creates the illusion of victory while the real battle—representation in leadership—remains to be won. One woman Chief Justice across 25 High Courts is not enough. Two women on the Supreme Court bench do not proportionally reflect the Indian people. While the appointment of the first woman Chief Justice of India in 2027 is symbolic, her 36-day tenure will be short-lived.

Justice Nagarathna recently underscored the need for a “sensitive work environment” to help women not only enter but also thrive in the judiciary. As we celebrate their increasing presence this woman’s day, let her words remind us that meaningful progress occurs when we are no longer counting “firsts”.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!