Analysis

Benches and backlogs

As the Court completes 75, it must be convinced that structural reforms to tackle pendency need to look beyond increasing bench strength

Tuesday next week will mark the completion of 75 years since the inauguration of the Supreme Court of India. As part of our year-long special series commemorating this milestone, we had sketched pen portraits of the first eight judges of this polyvocal institution. It was a motley crew representing four regions and three religions and which used to sit en banc to hear matters of importance in the new republic.

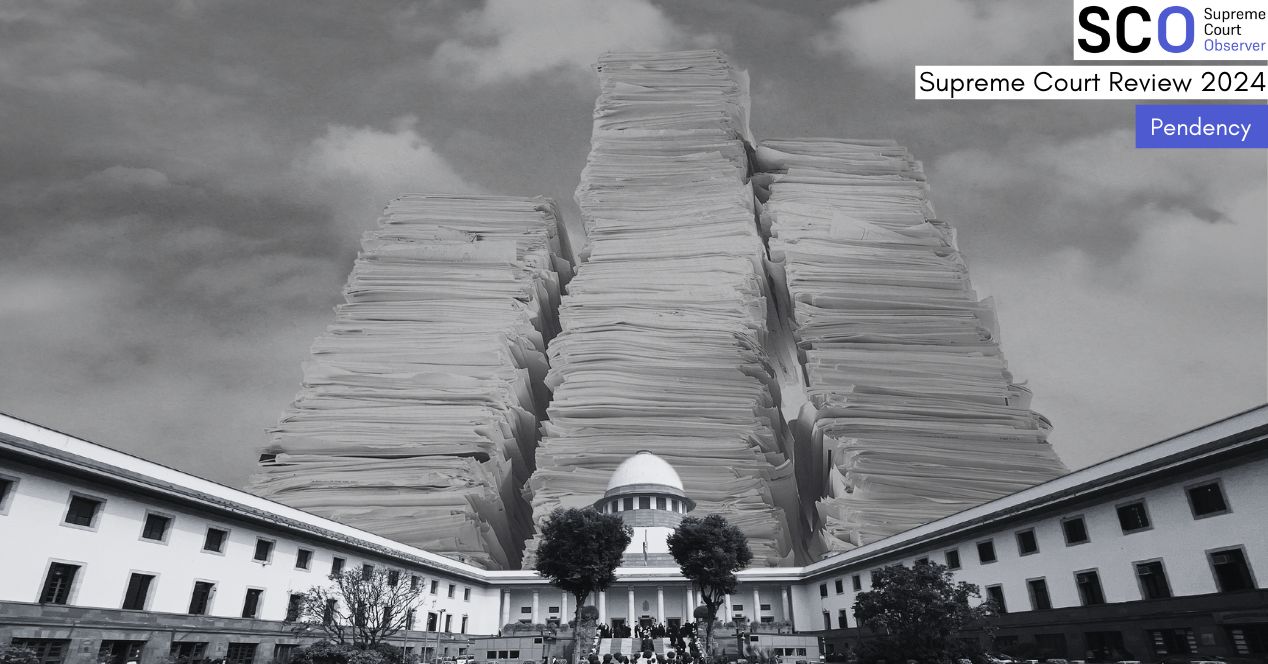

In the 75 years since, the sanctioned strength of the Court has been modified six times to reach 34—it was expanded to 11 in 1956, to 14 in 1960, to 18 in 1978, to 26 in 1986, to 31 in 2009 and finally to 34 in 2019. The expansion has been considered necessary as more cases reach the Supreme Court. As of December 2024, over 83,000 cases remained pending, an increase of nearly 14,000 since the end of 2020. At the close of 1950, the first year of the Court’s functioning, it was 690.

To be sure, India has one of the lowest judge-to-population ratios globally—21 per million of the population (it is 150 per million in the US). That’s still less than half of the 50 per million recommended in a Law Commission Report published in 1987. Last year, the outgoing Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud had remarked: “We simply need more judges, we are engaging with the government to increase the strength of the judiciary at all levels.”

But the fact is that increasing bench strength is not the silver bullet Chandrachud’s remark may have made it out to be. In 2019, author Gautam Bhatia had pointed out that a “coherent and consistent” jurisprudence will go further to address caseload than more judges. Bhatia noted that the polyvocality of the Court had led to a situation “where different benches of the SC have passed conflicting orders, and have, at times, purported to directly overrule each other…”.

There’s also merit in the argument that increased caseload is linked to the Court’s “ever-expanding jurisdiction”. Take, for example, the Court’s special leave jurisdiction. In 2023, the authors of Court on Trial, a data-based study, noted that appeals against judgements of subordinate courts comprise the majority of cases that reach the Court. In the Court’s formative years, SLPs were a rare phenomenon. Last year, former judge Madan Lokur noted that SLPs were meant to be used sparingly and only on the issuance of a certificate by the High Courts.

Another reason is the Court’s own moral compunction to ensure that justice is not denied. Funnily, it was the ‘PIL judge’ Justice Bhagwati who had cautioned about the flipside of this attitude in 1986: “Sometimes, we judges feel that when a case comes before us and we find that injustice has been done, how can we shut our eyes to it. But the answer to this anguished query is that the judges of the apex court may not shut their eyes to injustice but they must equally not keep their eyes too wide open…” But the Court seems not to have taken this advice to heart, evidenced by the haphazard evolution of its PIL powers. The result: more cases choking the Court’s docket.

Pendency has also not been helped by the government’s propensity for litigation. With the government being a party in nearly three-quarters of all cases admitted by the Court, throwing more judges at the problem might come across as ‘more courtrooms to litigate in’ by the country’s biggest litigator.

As we celebrate this major milestone of an institution that has often delivered what it promised, we mustn’t lose sight of the fact that it has progressively been overwhelmed by a burden that is spiralling out of control. At least partly, the situation is a result of its own doing. Its insistence on increasing bench strength, especially in recent times, should not be allowed to obfuscate a more fundamental debate about quality control.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!