Analysis

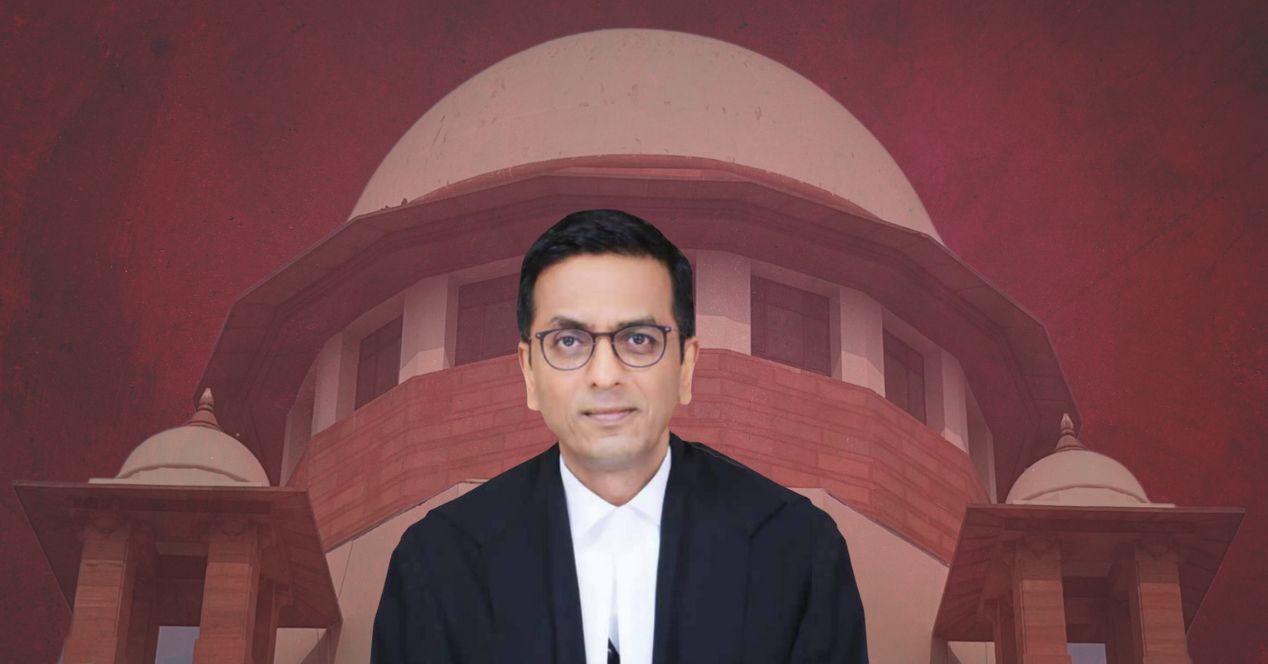

The top 7 dissents of Justice D.Y. Chandrachud

Here’s a list of 7 occasions when the outgoing Chief Justice diverged from the majority on conclusion or reasoning during his long tenure

On 10 November 2024, Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud will retire after an 8 years and 5 months tenure in the Supreme Court, including over two years as Chief Justice. During his time in the Court, Justice Chandrachud authored 613 judgements.

Justice Chandrachud has authored majority and concurring opinions in several landmark cases, including in a matter that recognised the right to privacy and one that decriminalised homosexuality. He is also believed to have been the chief drafter of the one unanimous judgement whose authorship was curiously not attributed to a single judge, the one that awarded the disputed Ayodhya title to the Hindu deity.

Notably, Justice Chandrachud has almost always been in the majority while deciding cases during his tenure at the Supreme Court. But a thread can be discerned as running through the rare occasions where he has dissented—the opinions have attempted to articulate rights and emphasise the Constitution’s transformative character.

Here, we curate a list of notable opinions wherein Justice Chandrachud has either arrived at some or all conclusions contradicting the majority, or arrived at the same conclusion as the majority but adopted different reasoning to get there. We have categorised these opinions into three types: full dissents, partial dissents, and concurring opinions with different reasoning. We list the opinions in chronological order.

Electoral Appeals | Full Dissent

Delivered on 2 January 2017

In 1990, C.D. Commachen challenged the election of his rival Abhiram Singh from Mumbai’s Santa Cruz constituency, on the ground that Singh made communal remarks in the run-up to elections. It sparked a 25-year-long litigation that finally concluded with a seven-judge bench decision of the Supreme Court in 2017. The question before the Court was whether the word ‘his’ in Section 123(3) of the Representation of People’s Act, 1951 (‘ROPA’), which prohibits a candidate from appealing to voters on the basis of ‘his religion, race, caste, community or language’, is meant to cover only the candidates, or both the voter and the candidates. The Court, by a 4:3 majority, concluded that appealing to the ascriptive identities of the candidate or the voter was a ‘corrupt practice’ under Section 123(3).

Justice Chandrachud’s 55-page dissent noted that the grammatical placing of ‘his’ in the provision, referred only to the candidate and not the voter. “The expression ‘his religion…’ must necessarily qualify what precedes, namely, the religion of the candidate in whose favour a vote is sought or that of another candidate against whom there is an appeal to refrain from voting,” he wrote. Further unspooling the history of the provision, Justice Chandrachud concluded that Parliament did not intend to extend the indication of ‘his’ to voters since that would lead to a situation where a candidate would be unable to speak about the injustices suffered by a segment of the population on the basis of caste, race, community or language.

Constitutionality of Aadhaar | Full Dissent

Delivered on 26 September 2018

In November 2012, retired judge K.S. Puttaswamy filed a challenge against the scheme for the Aadhaar card, which had become the primary document to access many government welfare schemes. Almost six years later, a five-judge bench of the Court ruled, in a 4:1 majority, that Aadhaar did not infringe rights under Articles 14, 15, 19 and 21. The majority also held that the Aadhaar Act was legitimately passed by Parliament as a Money Bill.

Justice Chandrachud’s dissent ran into 481 pages. He noted that participation in large-scale biometric systems such as Aadhaar should be based on the “informed consent” of citizens. In his view, the Aadhaar Act was not only silent on informed consent, but Section 28(5) actively prevented citizens from accessing their own data, thereby violating their right to privacy. He also found that the Aadhaar Act’s classification as a Money Bill was unconstitutional and undermined the role of the Rajya Sabha. “As a subset of the constitutional principle of division of power, bicameralism is mainly a safeguard against the abuse of the constitutional and political process,” he wrote.

Bhima Koregaon arrests | Full Dissent

Delivered on 28 September 2018

In August 2018, five activists were arrested by the Maharashtra Police. They were charged under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 on the ground that they incited caste-based riots on the sidelines of the Elgar Parishad event held earlier that year. The allegation further stated that they had links to Maoist groups that encouraged the violence to create dissatisfaction against the ruling establishment. A day after the arrest, five eminent citizens filed a joint petition in the Supreme Court challenging the arrests and demanding the formation of a Special Investigation Team (‘SIT’), to monitor the Maharashtra Police’s investigation and conduct an independent inquiry.

In September 2018, a three-judge bench of the Court, in a 2:1 majority, concluded that the accused were not entitled to demand a specific mode of investigation. But Justice Chandrachud’s 43-page dissent had a different view. He observed that the police investigation suffered from infirmities, one of which was the decision to approach the media while the investigation was underway. By selectively disclosing details to the media, the police had created public bias against the accused and cast “a cloud on the impartiality of the investigative process.” On these grounds, he ruled in favour of establishingan SIT.

Sabarimala temple entry | Concurring with different reasoning

Delivered on 18 September 2018

In a landmark ruling in 2018, a five-judge Constitution Bench led by Chief Justice Dipak Misra, held that the prohibition on women in their ‘menstruating years’ (aged 10 to 50 years old) from entering the Sabarimala Temple in Kerala, was unconstitutional. The customary prohibition was legitimised through a 1965 Kerala legislation which the majority struck down. While Justice Indu Malhotra’s dissent was resounding, Justice Chandrachud’s concurring opinion also raised a divergent view.

The crux of the discussion came down to the Essential Religious Practices (ERP) test — an assessment to determine whether a religious practice (protected under Article 25) is unconstitutional or not. In State of Bombay v Narasu Appa Mali (1951), the Supreme Court had ruled that personal laws were beyond the scrutiny of fundamental rights. As per the ERP doctrine, if a practice was found to be integral to a religion, the Court generally upheld the practice’s constitutionality without undertaking a fundamental rights assessment.

The majority opinion of CJI Misra and Justice A.M. Khanwilkar went down this route, analysing historical records of the practice, to conclude that it was not ‘essential’ to the community, and therefore unconstitutional. Justice Chandrachud, however, while concurring on the conclusion, seemed to voiced discontent against the majority’s reliance on the ERP doctrine: “By reserving to itself the authority to determine practices which are essential or inessential to religion, the Court assumed a reformatory role which would allow it to cleanse religion of practices which were derogatory to individual dignity. Exclusions from temple entry could be regarded as matters which were not integral to religion. While doing so, the Court would set up a progressive view of religion. This approach is problematic.”

Some have suggested that Justice Chandrachud’s opinion opens the door for a complete overhaul of the ERP doctrine. However, under one of the conclusions in his judgement, Justice Chandrachud states that the exclusion of women from temple entry was not an essential religious practice.

Justice Chandrachud’s 165-page concurring opinion also expanded the scope of Article 17, which prohibits untouchability. While ‘untouchability’ has traditionally been recognised as a caste-focussed practice, he noted that Article 17 could also apply to untouchability faced by menstruating women.

RTI versus Judicial Independence | Concurring with different reasoning

Delivered on 13 November 2019

In November 2009, the Central Information Commission ordered the Supreme Court to disclose certain correspondence between the Collegium and the government, in furtherance of a request under the Right to Information Act, 2005. The Court appealed the order. In 2019, a five-judge Constitution Bench ruled that judicial independence was not contradicted by the need for transparency, and there have to be case-by-case assessments of whether a piece of information should be disclosed, or not.

While Justice Chandrachud signed the majority opinion of Justice Sanjiv Khanna, his 112-page concurring opinion (longer than the majority opinion) had some additional observations. While all judges agreed that information cannot be curtailed simply because it hampers the free and frank expressions of constitutional functionaries, Justice Chandrachud emphasised the importance of clearly defined selection criteria for judicial appointments.

Similarly, Justice Chandrachud’s analysis on information being disclosed on a case-by-case basis was unique. He batted for the application of the triple test (first evoked in the Puttaswamy right to privacy judgement) in situations where an individual’s right to privacy and another’s right to information were pitted against each other: existence of a law, legitimate State aim, and proportionality. Since the RTI Act automatically fulfils the first two tests, every RTI request that affects privacy must be tested on ‘proportionality’. He suggested that the Central Public Information Officer must justify with “detailed reasons”while deciding matters under Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act (which allows RTI rejection on privacy grounds).

Review of Aadhaar judgement | Full Dissent

Delivered on 20 January 2021

After the Aadhaar judgement was delivered in 2018, seven parties filed review petitions in the Supreme Court, arguing that the decision suffered from “errors apparent on the face of the record.” They argued that the Court had failed to consider vital material placed before it, and used contradictory logic instead. After hearing the review in-chambers, the five-judge bench dismissed the review by a 4:1 majority. Justice Chandrachud dissented, reiterating his stance as in the original Aadhaar case.

In the Aadhaar judgement, the majority had noted that the decision of the Speaker of the Lok Sabha to categorise a bill as Money Bill could be judicially reviewed. However, another five-judge bench in Rojer Mathew v South Indian Bank Ltd (2019) noted that the scope of judicial review of Money Bills had not been “substantially discussed” in the Aadhaar case, and referred the question to a seven-judge bench. Justice Chandrachud, in this Aadhaar review dissent, noted that a bench of equal strength had doubted the 2018 judgement’s reasoning, so the review should not be dismissed at this stage because a larger bench was considering the question.

Marriage Equality | Partial Dissent

Delivered on 17 October 2023

In October 2023, a five-judge bench held that there was no fundamental right to marry, for queer people. The Court also refused to recognise the rights of LGBTQIA+ persons’ under the Special Marriage Act.

While the decision was unanimous, Chief Justice Chandrachud’s 247-page part dissent (significantly longer than Justice S.R. Bhat’s 89-page majority opinion, Justice P.S. Narasimha’s 13-page concurring judgement and Justice S.K. Kaul’s 17-page part dissent) raised some crucial issues.

Firstly, he disagreed with Justice Bhat’s majority holding that the Supreme Court was not the right forum to recognise queer person’s right to marry, by noting that it fell squarely within the scope of judicial review and did not violate the separation of powers. Justice Chandrachud (along with Justice Kaul) also diverged from the others by noting that queer couples have the right to enter into a civil union and it flows from Article 19. Justice Bhat’s majority opinion had noted that recognising such a right, would require a separate regime for registration, laying down the conditions of a valid union, setting eligibility, age restrictions, divorce, alimony and a bouquet of other rights that are ancillary to marriage.

Finally, CJI Chandrachud diverged from the majority while holding that non-heterosexual, unmarried couples can also adopt children. He observed that Section 57 of the Juvenile Justice Act could not prohibit unmarried couples from adopting children just because it uses the word “spouse” and not “unmarried couples.” Justice Bhat’s majority opinion noted that a complete reading of Section 57(2) indicated that it was only concerned with joint adoption by married couples.

CJI Chandrachud’s holding in Supriyo thus provides a possibly valuable precedent for future litigations regarding civil unions, adoption rights and more consequential rights for queer people.