Analysis

“Ayodhya is a storm that will pass”: Justice Ahmadi on his 1993 dissent

An excerpt from CJI Ahmadi’s biography written by his granddaughter captures the pressures of being a dissenting judge in a landmark case

A few weeks after the illegal demolition of the mosque, the then President of India, Shankar Dayal Sharma made a Presidential Reference to the Supreme Court under Article 143(1) of the Indian Constitution, seeking the Court’s opinion on whether a Hindu structure existed at the site of the Babri Masjid before it was built. Meanwhile, the Centre passed an Act, which allowed it to acquire approximately 67 acres of land in and around the Babri Mosque. This was the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act which was subsequently challenged by Ismail Faruqui and brought to the Supreme Court in 1993. The bench comprising Chief Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah, Justice A.M. Ahmadi, Justice G.N. Ray, Justice S.P. Bharucha and Justice J.S. Verma declined to answer the Presidential Reference. The majority of the judges, Justices Venkatachaliah, Verma and Ray dismissed it as ‘superfluous and unnecessary’.

The minority opinion by Justices Ahmadi and Bharucha also declined to answer the Reference, stating that the Supreme Court bench had no possible way of knowing whether a Ram temple existed on the site before the Babri Masjid was built there. Also, the words ‘Hindu religious structure’ and ‘Ram Temple’ had become somewhat synonymous, further clouding the issue. Ahmadi explained this in further detail in an interview several years later:

The dispute, it will be remembered, was that a Rama temple had stood on the disputed site and it was demolished to make place for the disputed structure (Babri Masjid); the question posed, however, is: Was there “a Hindu temple or any Hindu religious structure” on the disputed site? Secondly, the salient fact as to whether the temple, if any, was demolished to make place for the disputed structure is not to be gone into . . . In other words, we were being asked to give an opinion on whether there existed a temple or a Hindu religious structure, not whether a Rama temple existed. However, the cause of the dispute was that a Rama temple had been demolished to build the Babri Masjid in 1528 AD. It was akin to shifting the goalpost, so to speak.

In a rather scathing paragraph, the minority opinion pointed out that it was clear that the government did not intend to bind itself by the judicial decision. ‘It leaves us in no doubt that even in the circumstance that this Court opines that no Hindu temple or Hindu religious structure existed on the disputed site before the disputed structure was built thereon, there is no certainty that the mosque will be rebuilt.’

In doing so, the Court sent a resounding message to Prime Minister Rao; it also highlighted that the Reference sought to ‘favour one religious community and disfavour another.’

Simultaneously addressed in conjunction with the Presidential Reference was the matter of Ismail Faruqui vs. Union of India – a challenge to the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act – an attempt by the Central Government to gain control of administration and maintenance of the Ram Janma Bhumi-Babri Masjid structure along with its premises. The attention of the entire nation was riveted on the proceedings of this high profile case, for by now it had become abundantly clear that this decision would define the fate of not only the Babri Masjid but also the secular character of India.

But although the bench would ultimately rule in favour of the Centre, declaring the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act valid, this judgement was not unanimous. The minority of the bench that dissented from the majority opinion consisted of Justice Ahmadi and Justice Bharucha, who both considered the Act to be unsecular and constitutionally unfit. The bench struck down one of the clauses that sought to end all legal proceedings related to the dispute.

Under intense pressure to succumb to the majority on the bench, Justice Ahmadi put pen to paper many decades later, revealing for the first time details about that period. Judicial deliberations on the Reference having concluded, a meeting of the bench was called to discuss the matter of Ismail Faruqui vs. Union of India. As he walked into the room, Ahmadi noticed that while Justices Venkatachaliah, Ray and Verma were present at the meeting, strangely, Justice Bharucha was not. The judges present began the meeting with the perfunctory opening remarks, and then produced a draft judgment that had evidently been prepared in advance, asking Justice Ahmadi to peruse and endorse it. Ahmadi raised a primary objection that Justice Bharucha was not present at this meeting, and it was improper to conduct these discussions in his absence. To this he was told, ‘Once we four agree, he too will agree.’ Uncomfortable with this reasoning, Ahmadi nevertheless agreed to look at the draft. Having read through the draft, however, he found that in validating the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act, the bench would be tacitly sanctifying the acts of trespass and destruction that had taken place – all offences under the Indian Penal Code. Not least because there was no mention of any adverse consequences for the parties who had allowed or participated in the demolition, nor any orders of status quo against both communities offering prayers at the site. Of course, he was unwilling to do this. Recognizing the meeting for what it was, Ahmadi told the Chief that he would sign their draft if they amended it to include the allocation of a small piece large enough for a moulvy (Islamic priest) to spread his mat and offer namaaz on the land parcel, thereby maintaining the right of the Muslims to offer prayers there too – especially since the effect of the Act would include retaining the idols where they had been placed and requiring the pujas to continue in the manner that they had been done since the demolition, indefinitely. Recoiling at the suggestion, the Chief Justice and his two colleagues refused outright. At this point Justice Ahmadi expressed his inability to continue further discussions on the topic and left. It is through Justice Ahmadi’s own personal writings that we now have insight into the precise details and considerations of the bench during this profoundly significant case.

Walking away from the meeting, Justice Ahmadi appeared outwardly calm, but was seething inside. Once inside the official white Ambassador car, he drew the little lace curtains across the car windows for privacy. Face flushed with fury, he wrenched his bands off. He was sure he had left the three judges frustrated and bitter. The next day, he spoke with Justice Bharucha, and they agreed to record their dissent as neither one of them could agree with the majority view.

Poised to take over as the next Chief, Ahmadi knew that there is many a slip between the cup and the lip. He knew he was stepping into the bullring – defying the Chief Justice and the executive on this high profile matter with such high stakes could mean risking it all, his career, his shot at the Supreme Court’s top spot. The pinnacle of success was within grasp, but dissent at this stage could lead to supersession by a junior judge as retaliation. There was precedent for such things – it had happened before in the history of the Indian judiciary. He also knew that the nature of his relationship with the Chief Justice of India was an open secret within the courtroom corridors as well as in government circles.

But, in the depths of his being, he realized the truth. This wasn’t a choice; it was a litmus test. In a test of integrity and ideals, there really was no option.

We know of the extent of the pressure he was under at this time not only through Justice Ahmadi’s private writings and conversations with him, but also through the memories of his children and grandchildren. One that sticks out is a particular phone call that was received one evening when the family was in the middle of dinner. The secretary in the office at the time called on the phone in the family room, which also doubled up as an informal dining room where the family would gather to spend time together on most evenings. Answering the intercom, Justice Ahmadi asked for the call to be transferred to his bedroom – a clear indication that the contents of the call were expected to be confidential. Leaving his mound of khichdi and mutton curry half eaten on the plate, he left the room to attend to the phone call. Continuing with our meal, we thought nothing of this somewhat common occurrence, until a few minutes later we heard the booming voice of Aziz Ahmadi thunder from all the way down the bottom of the corridor, ‘I don’t care about becoming Chief Justice, I won’t do it!’ Like a sharp slap, the room fell into stillness as we exchanged uneasy glances and waited for him to return to the dining table. That night he did not.

Because he never revealed who was at the other end of that phone call, all we could do was speculate.

As ever, Justice Ahmadi, when upset, would retire to his haven, his work. Some days, he would emerge only for meals, eating quickly and retreating again to his baithak on the bedroom floor to prepare for the next day before finally turning in for the night, hours after everyone else had. A man who required no more than five, sometimes four hours of sleep each night, he did most of his thinking when the world was dark and quiet. Pacing on the carpeted floor, he fought the numbness in his legs from hours on the floor. In the morning, a stack of carefully drafted notes in his tiny, angular handwriting was ready for his secretaries to type out. Positioned across from the secretary in his office, he’d unleash a torrent of dictation. Scribbling furiously in shorthand, the secretary transcribed his judgements, the marathon sessions stretching for hours on end, broken only by the cups of black tea fuelling them both.

When I approached Justice Bharucha shortly after Justice Ahmadi’s demise for more clarity on the machinations of the time, he stated that there was much that had taken place, but he did not wish to elaborate on the ‘persuasions’ that were attempted before he and Justice Ahmadi took the decision to disagree with the majority on the bench and write their dissenting opinion. Instead, he encourages the public to read the minority judgement to understand why the two judges found the majority view unacceptable.

Finding the Act to be unsecular and unconstitutional, the opinion authored by Justice Bharucha had noted,

…no account is taken of the fact that the structure thereon has been destroyed in a most reprehensible act (sic)… No account is taken of the fact that there is a dispute in respect of the site on which puja is to be performed… the disputed structure was being used as a mosque; and that the Muslim community has a claim to offer namaz thereon…’ ‘the perpetrators of the deed struck not only against a place of worship but at the principles of secularism, democracy and the rule of law… ’ ‘When… adherents of the religion of the majority of Indian citizens make a claim upon and assail the place of worship of another religion and, by dint of numbers, create conditions that are conducive to public disorder, it is the Constitutional obligation of the State to protect that place of worship and to preserve public order, using for the purpose such means and forces of law and order as are required. It is impermissible under the provisions of the Constitution for the State to acquire that place of worship to preserve public order… To condone the acquisition of a place of worship in such circumstances is to efface the principle of secularism from the Constitution’

The dissenting opinion also expanded on the secular character of the state.

Secularism is thus more than a passive attitude of religious tolerance. It is a positive concept of equal treatment of all religions. This attitude is described by some as one of neutrality towards religion or as one of benevolent neutrality… What is material is that it is a constitutional goal and a basic feature of the Constitution… Any step inconsistent with this constitutional policy is in plain words, unconstitutional.

Poignantly, it also stated, ‘Ayodhya is a storm that will pass. The dignity and honour of the Supreme Court cannot be compromised because of it.’

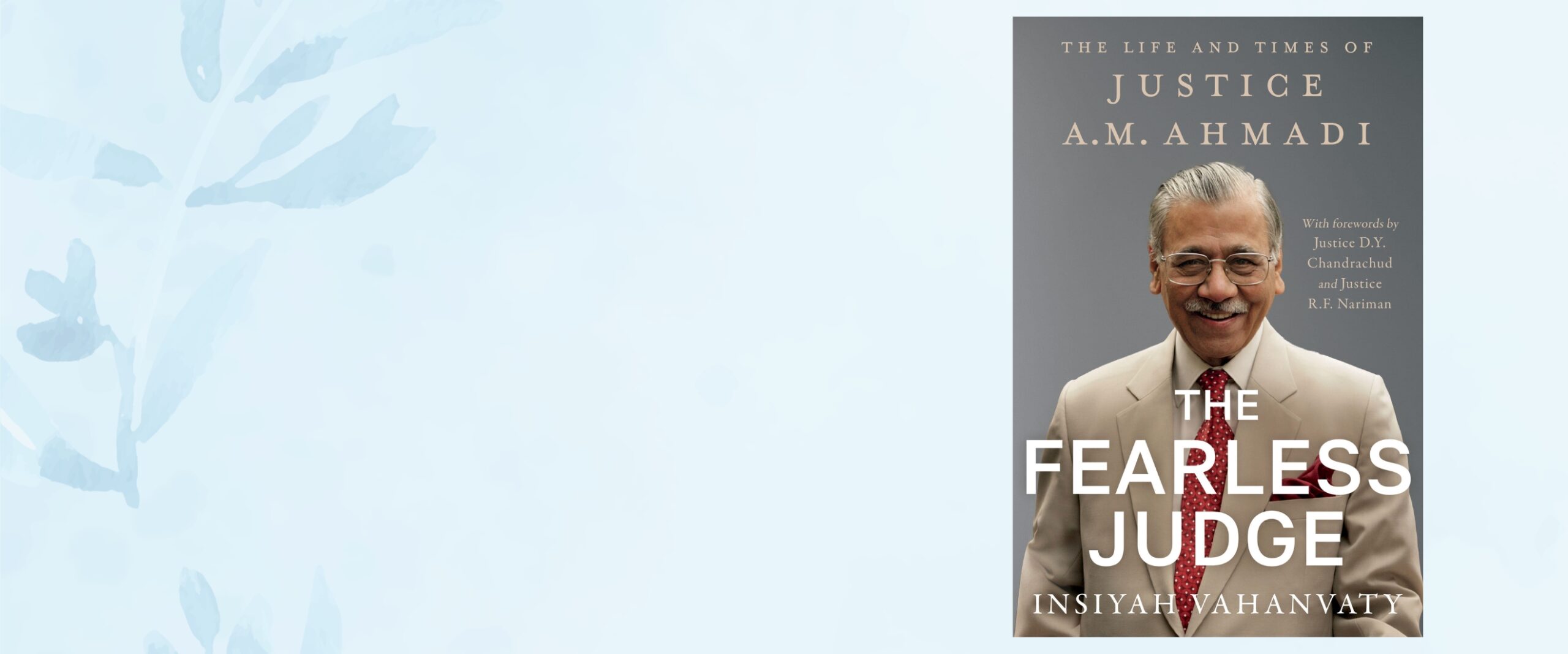

(This is an excerpt from ‘The Fearless Judge: The Life and Times of Justice A.M. Ahmadi’, published recently by Juggernaut Books.)