Analysis

The Listing Game

Listing at the SC has been plagued by uncertainty. As the Chief nears the end of his tenure, the call for reform is reaching its crescendo

Recently, a letter written by Nikhil Jain, Honorary Secretary of the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association (SCAORA), to the Secretary General of the Supreme Court’s Registry garnered attention in legal circles. The letter, written on behalf of 137 Advocates-on-Record, highlighted the constraints and difficulties faced by SCAORA members in the filing, registering and listing of cases.

The Supreme Court Registry is an administrative body responsible for the daily listing of cases, on the instruction of the Chief Justice. The Registry receives and processes all case documents, checks them for completeness and defects and assigns case and diary numbers. It also prepares the daily cause list—a roll of cases that are scheduled to come up before the benches of the Court.

The displeasure with the Registry is not limited to the Bar. On 27 August, for instance, a Division Bench of Justices A.S. Oka and A.G. Masih had pulled up the Registry for not listing a Special Leave Petition despite an Order. The Court’s Order said:

“When there is a specific order of the Court that a particular petition shall be listed, the minimum we expect from the Registry is that there is some explanation placed on record why order of this Court is not complied with.”

Earlier this year, another bench led by Justice Oka had raised a similar concern when a Civil Appeal matter was not listed before the bench. Even as the bench noted that they would not take any action against the Registry, the Order stated that it was “worrying” that some members of the Registry staff had “bye-passed” the judicial order directing listing.

To understand what’s going on at the Registry, the Supreme Court Observer spoke to several advocates and practitioners at the top court. Attempts to reach the Registry—on phone and email—for comment earlier this week did not elicit a response till the time of publishing. Before we get to the bottom of the issue, let’s run through the Registry’s role in listing cases.

The filing and listing process

The Registry is divided into two wings: judicial and administrative. The judicial wing is responsible for case management, from the stage of filing to disposal. The administrative wing manages all the non-case management related work—exams, scheduling, human resources, inventory and more. These two wings are further divided into divisions, branches, sections and cells which deal with defined subject matters such as type of case and region, etc.

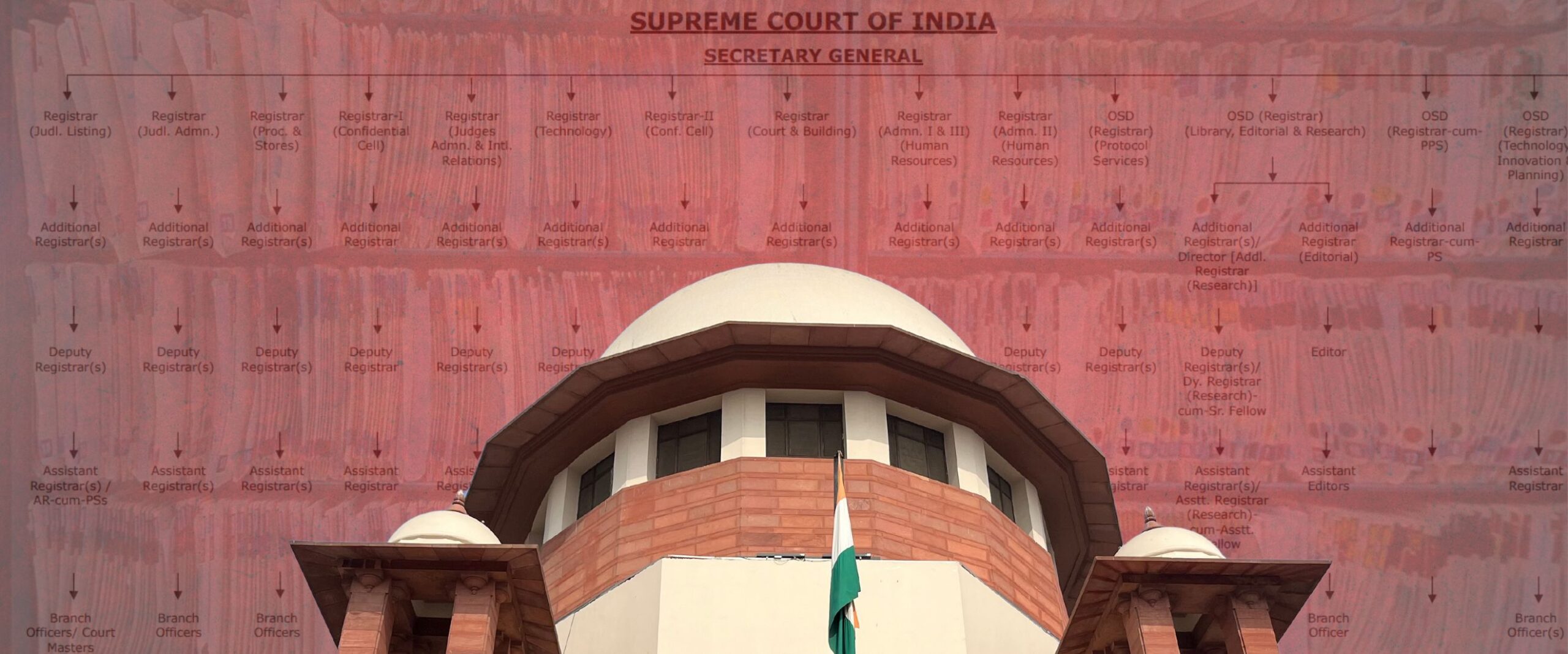

The Secretary General is the highest administrative officer of the Registry. Ten Registrars, five Officers on Special Duty (OSD), and several Additional Registrars, each managing distinct branches, assist the Secretary General. Each Registrar is also in charge of a distinct function of the Registry. There is a head Registrar and a Registrar for Listing, Judicial Administration, Technology, Confidentiality and so on.

According to the Supreme Court’s Handbook on Practice and Procedure and Office Procedure, a case is filed by a party or their agent or their Advocate-on-Record at the Filing Counter of the Registry. The functions of the Filing Counter can be broadly divided into four categories: (i) assigning a diary number, (ii) scrutiny and defect identification (iii) registration and (iv) verification (confirming whether identified defects have been cured).

“When a case is filed at the Supreme Court either online or in person, the first thing is that a ‘diary number’ is assigned. This is the number that remains with the case throughout,” Raghav Gupta, a Delhi-based advocate, told me. “The Registry typically takes two to three days to identify any defects. If defects are found, petitioners then have 28 days to address these issues. After rectification of defects, all case documents are photocopied, a case number is assigned, and then it is registered. Finally, the application is verified before the case is listed,” he said.

The Handbook has this to say about how the causelist is prepared: “The Registrar (J-I) shall list the cases before the Benches in accordance with the roster under the directions of the Chief Justice.” In practice, the degree of the Chief’s involvement in the listing process is unclear and opaque, leading to a lack of consensus about the system even among practising advocates.

“It is an everyday task,” said a practitioner who is part of the chambers of a recently designated Senior Advocate. “Whenever a cause list is prepared for a day, it involves a discussion between the Registrar (Listing), the Registrar (Judicial), the Head Registrar and the Chief Justice. A daily cause list is prepared after consultation with the Chief.”

However, Gupta and another Delhi-based advocate, who did not want to be named, told me that the listing is an “automatic” process. “Fresh matters are listed according to the Roster and part-heard matters are listed per the directions of the bench,” this Delhi-based advocate said. “This process is relatively straightforward for most cases. Matters follow a standard route unless they involve politically sensitive issues or unclear aspects that require clarification. In such instances, the Registry will present the case to the Chief Justice for guidance and appropriate orders.”

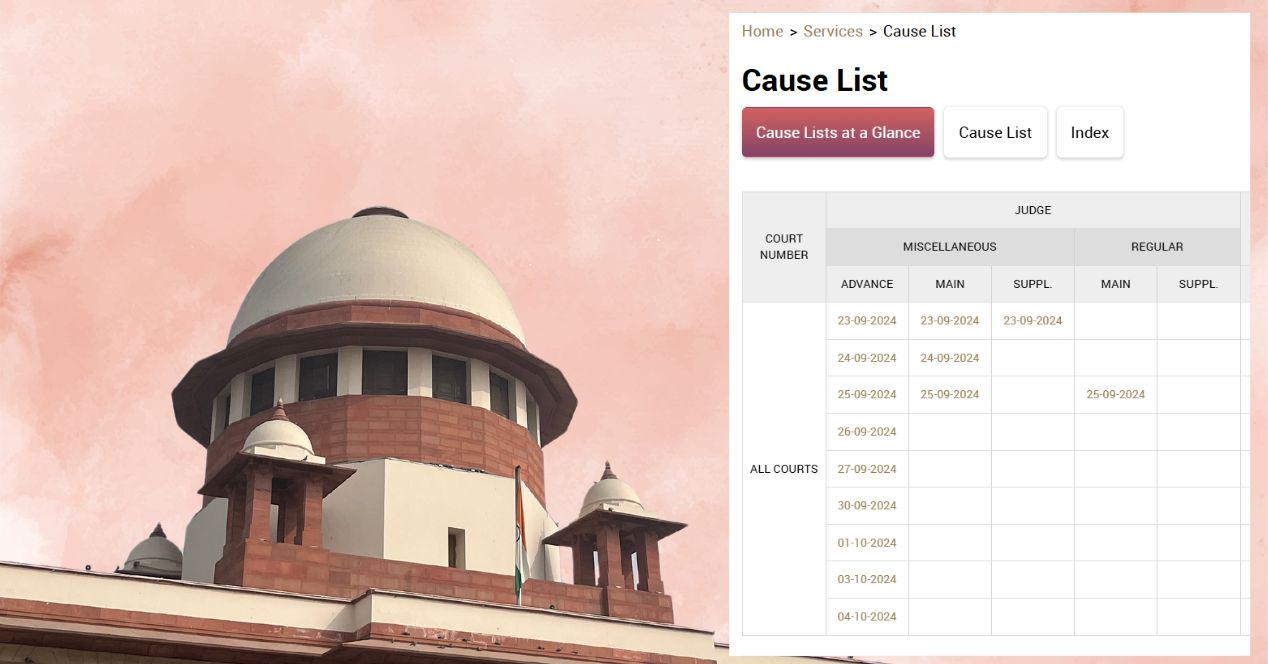

Fresh cases are added to the cause list in chronological order. Pending cases are proposed for listing by the Dealing Assistants. Admission hearings for fresh cases are scheduled on Mondays and Fridays; regular hearings take place on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Thursdays.

To ensure timely hearings, the papers of cases which were previously admitted but haven’t come up for hearing are uploaded to the Court’s intranet at least two weeks prior to the listing date. Every Friday, the Court also releases an Advance List of regular hearings for matters scheduled on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday of the next week. Additionally, after preparation of the cause list, judges may direct other matters to be listed. These are put together in a supplementary list.

Procedural rules are relaxed for urgent or emergency matters. In these circumstances, an email is sent to an official email address, conveying the “urgency” in a matter. A case may be “mentioned” before the Chief or a particular bench in the morning, after sending an email to the Court.

During the term of the current Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, mentioning takes place when the bench assembles every morning. If the Chief allows a mentioned case, it is listed for hearing the very next day. Harshit Anand, a Delhi-based advocate, told me that the Chief usually conveys his decision on allowing or rejecting mentioned cases to the Registrar during the lunch hour.

Inordinate delays

The SCAORA letter complained that the Registry was delaying the notification of defects. Second, once the defects were rectified, there was further delay. Third, in urgent matters, once a matter was registered, it could take days or even weeks for it to be verified.

The advocate who didn’t wish to be named confirmed that the Registry seemed to be working at its own pace. “All these things take so much time that the urgency of the matter starts getting lost. So for instance, you could be filing something at express pace, but the Registry will take its own sweet time,” he said.

Anand told me that the Registry is “maybe a little overworked” because of the large number of cases that are instituted at the Supreme Court daily. “The Supreme Court is a very, very busy court,” he said. The backlog is undeniable. For some context, in August 2024, the Court worked for 18 days and received 5530 cases. This means 307 cases were filed per day, on average. As of last month, 15,901 unregistered cases were pending before the Supreme Court, an indication of the workload of the Registry.

Blurry lines between administration and adjudication

One of the complaints I heard from the advocates was that the Registry often assumes an adjudicative role in scrutinising new cases and applications. “The Registry does not have any judicial or quasi-judicial powers,” said Anand. “So the Registry cannot ask you as to why you are filing this petition and not that petition. But they often do, and this creates some sort of human arbitrariness. Because it’s not one person who is managing the Registry. It is also divided into different parts.”

This concern was echoed by Gupta. “The accuracy of documents is up to me and the judge,” he said. “The Registry’s role is limited to administrative checks. While Registry staff are well-educated and may grasp the case’s outcome from the synopsis, their focus should be on procedural compliance, not substantive evaluation.”

Gupta also spoke about advocates having to repeatedly follow-up with the Registry on the listing of fresh matters. “If a case is assigned to an officer who’s on leave, no one else will be allocated,” he said. “In this scenario, clerks or advocates must visit the Registry in person and inquire about the concerned officer and discover they’re absent. ”

Gupta pointed out another issue. “Registrars and parties sometimes collude to delete matters or get them listed. Sometimes, parties may prefer a specific bench to hear their case. If they have connections within the Registry, they may influence the assignment. Well-connected parties, larger firms and prominent names often get priority.”

The Delhi-based advocate who chose to remain anonymous pointed out that even defect-free matters are not a shoe-in to be listed immediately at the Supreme Court. “At the Delhi High Court, for instance, there is a noting on the cause list itself that all those matters which are defect-free shall be placed before the Court the next day itself. But in the Supreme Court, even if a matter is defect-free, there are so many stages through which it goes—registration, verification.”

There’s also the issue of the Court being seemingly more accommodating of fresh matters. “One of the things which happens often is that the bench will say ‘list a matter after two weeks’ or ‘list a matter after four weeks’ and the matter just goes into a bit of a blackhole,” said Shivam Singh, a Delhi-based advocate.

In the course of our daily court reporting, our team has noticed this too. To take a recent example, the Supreme Court has heard the Kolkata hospital rape and murder case four times so far. On the first three days, the bench gave a specific date for the next listing. On the fourth day of hearing, on 17 September, the Chief’s bench directed the case to be listed “after a week”. The case was not listed the next week.

Some of the advocates I spoke to said that the bench often contributes to exacerbating delays and the uncertainty around listing. “In mentionings, I’ve reminded judges that the bench had ordered for a matter to come on a particular date, but the Registry hasn’t listed it,” said an advocate, who has also been a judicial clerk in the Supreme Court. “I’ve also seen other advocates do this. But judges have often disregarded our plaints. They say ‘It’ll come up when it comes up, don’t be impatient.’ Justice Oka passed that order pulling up the Registry, yes, but he is an exception.”

The former judicial clerk added that when they approached the Registry about a case not having been listed despite an order, the staff asked them to file an “urgency letter”. “And then when you move that letter and it gets rejected by the judge, it’s hard to even get a listing after mentioning. And you can’t say anything directly to the Registry.”

The Delhi-based advocate mentioned above told me that judges’ approach to listing is often influenced by the tradition of the High Courts they are coming from. “The Bombay, Patna and Allahabad High Courts, for instance, do not have a system in place for a firm or a specific date for first listing. So if you have a Chief from the Bombay High Court, he has never really come across a process where matters are necessarily listed within 48 hours of filing unless they’re specifically mentioned,” said this person, who also suggested that judges from the High Courts of Delhi and Madras may be more proactive with listing.

When I put this to Anand, he said that this difference in approach was unavoidable. He pointed out that, ultimately, the responsibility of allocation rests solely with the Chief Justice as the Master of the Roster. “A lot of power is placed in the Chief Justice,” Anand said. “The Chief sending a particular kind of matter to a bench with a disposition can have a drastic impact on the outcome of a case.”

Is technology the solution?

The Delhi-based advocate felt that the problem can be addressed by introducing a practice where “all defect-free, fresh matters come up on the next available miscellaneous days.” They noted that several High Courts, especially those with Original Jurisdiction, already had this system in place.

Their suggestion was to consider listing cases that have had their defects cured without waiting for verification. “Now, we need to refile after curing defects, and then it goes through the cumbersome process all over again. While manual oversight is necessary to ensure accuracy, excessive human intervention can hinder progress.”

This is an idea that has currency. Last month, research organisation Daksh published a working paper titled “The Case for Improved Causelists”, which advances the idea of a fully automated cause list to improve predictability, efficiency and inclusivity. Based on the research, Daksh has created the prototype of a model cause list.

There’s hope that the Court will be receptive to such ideas. All the advocates I spoke to said the listing process had changed for the better since Justice Chandrachud took over as Chief. “Much has improved in terms of keeping lawyers updated about progress,” Singh said. “There is an online system, everything is in the public domain, and you also get information when a matter has been listed or moved from one court to another.”

Anand added that the issue of a case not finding a place in the cause list after the bench has assigned a date may be overstated. “In the last couple of years, it has happened sparingly,” he said. “Slip-ups have happened in politically sensitive matters, that’s why there has been so much noise around these mistakes. Now, why have they happened? There is no answer because no accountability has been fixed. Otherwise, I think if you ask me overall, then yes, technology has been used quite well by the Supreme Court in the last two years.”

Gupta struck a cautious note when asked about the possibility of a fully automated cause list. “While technology can streamline processes, human intervention is essential for critical stages like curing defects and verifying SLPs,” he said. “Full automation isn’t feasible, as systems can only parse documents to a limited extent. Human oversight is necessary to identify mistakes and detect inconsistencies. Take the example of a document with missing pages. A system might recognise the case number, bench, and front and back pages, but only a human can spot that crucial pages are missing from the middle.”

Ticking clock for Chief’s retirement

The practitioners I spoke to, told me that the issues raised in the SCAORA letter can be addressed by fixing deadlines for identifying defects, completing scrutiny after curing defects, and for the verification process. Gupta batted for a strict timeline. “If they find defects and tell me that I have to cure them in 28 days, then there must be a time limit on the Registry also to identify the cured defects and list the case within a fixed period.”

Anand told me that the Registry could do well to get rid of some of its “bureaucratic requirements”. “These also display non-application of mind, to an extent. Instead of asking superfluous questions, it would be better for the Registry to process the matter objectively and place it before an appropriate bench.”

Advocates are hoping that some listing reforms or processes are put in place by Chief Justice Chandrachud before he retires on 10 November. The word in the chambers of AoRs is that this will be the parting flourish they will appreciate the most.