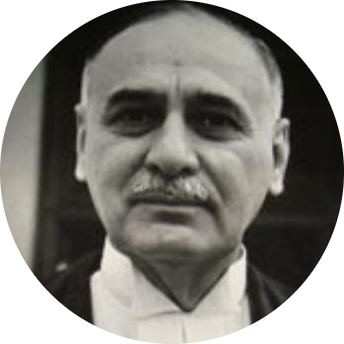

Vivian Bose

Vivian Bose

Former Judge of the Supreme Court of India

Assumed Office5th Mar, 1951

Retired On9th Jun, 1956

Previously

Chief Justice of Nagpur High Court1949 to 1951

Judge of Nagpur High Court1936 to 1949

Additional Judicial Commissioner Nagpur 1931 to 1934

Government advocate and Standing Counsel to the Government of Central Provinces and Berar1930 to 1936

Principal of University College of Law, Nagpur 1924 to 1930

Profile

Early life and education

Justice Vivian Bose was born on 9 June 1891 in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Though the Bose family considered Nagpur to be their home, Bose’s father, Lalit Mohan Bose was posted in Ahmedabad as a government engineer. Bose’s mother was English. In 1874, Justice Bose’s grandfather, Sir Bipin Krishna Bose, a lawyer, philanthropist, educationist and political figure with Bengali origins had made the shift with the family to Nagpur. Justice Bose’s uncle was a judge in the Nagpur judicial commissioner’s court. The family was well-connected, as they were closely associated with the government of Central Provinces and Berar.

At 15 years of age, Justice Bose moved to England to study. He first completed his secondary education from Dulwich College in Cambridge, and graduated with a B.A. (Honours) and LLB from Pembroke College in Cambridge in 1913. That year, he was also called to the bar from Middle Temple. Justice Bose met Justice Fazl Ali in London, who he later joined as a judge of the top Court. Jawaharlal Nehru was also studying law in London at this time and was called to the Inner Temple in 1913. That year, Justice Bose also returned to Nagpur to begin his practice, which he steadily kept up for 38 years.

In 1930, Justice Bose married Irene Mott, an American born social worker and author of prominent children’s books. Irene’s father, John Mott, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946 for the “creation of a peace-promoting religious brotherhood across national boundaries”.

Career as an advocate

The Nagpur High Court was established in 1936. Until then, Justice Bose’s career as an advocate thrived, with regular appearances in the Nagpur commissioner’s court, administering the Nagpur University College of Law as its first principal from 1924 to 1930, assisting as a government advocate and Standing Counsel for the Central Provinces and Berar from 1930 onwards, and being officiated twice as an additional judicial commissioner, between 1930 and 1934. In 1936, when the Nagpur High Court was instituted, Justice Bose was appointed as one of its first judges.

Career as a judge

Justice Bose served as an associate judge in the Nagpur High Court for 13 years. During this time, he served as the chairperson of the Bilaspur Commission of Inquiry looking into election malpractices in 1938, and headed the Hill Investigation Tribunal in 1940. He continued to serve at the Nagpur High Court as India became independent. On 20 February 1949, he was appointed as its Chief Justice.

He held this position for nearly most of his career. Just when he was about to approach his retirement, Justice H.J. Kania, who was set to become the first Chief Justice of India, invited Justice Bose to join the inaugural roster of the Supreme Court of India. On 5 March 1951, Justice Bose was sworn in as a Supreme Court judge.

He became the first Christian, and the only Eurasian judge in the top Court’s history. He reached his age of retirement on 9 June 1956. However, the second Chief Justice of India S.R. Das invited Justice Bose to return to the bench under Article 128 of the Constitution. Article 128 confers the power upon the CJI to invite a former Supreme Court judge to sit in the top Court’s proceedings and act as a judge. On 9 September 1957, Justice Bose started his second tenure as a Supreme Court judge. He retired about a year later, on 30 September 1958.

Commissions, inquiries and controversies

During his second tenure as a judge of the Supreme Court, in May 1958, Justice Bose was appointed as the chairman of a board of inquiry investigating the ‘Mundhra scandal.’ This was independent India’s first major scandal in which a Calcutta-based industrialist, Haridas Mundhra, had colluded with the government owned Life Insurance Corporation for investing over a crore rupees into his own troubled companies. In 1958, a report of an inquiry commission led by Justice M.C. Chagla had implicated various finance ministry officials in the scandal. Justice Bose’s commission published a second report which claimed that there had been quid pro quo transactions between Mundhra and the Congress government. Enraged, Nehru stated that Bose was “lacking in intelligence.” He later apologised and the two mended their relationship. That same year, Bose also headed the Dalmia-Jain Commission of Inquiry looking into alleged improprieties by V.H. Dalmia and Shanti Prasad Jain, two prominent industrialists.

After the Court

Between 1959 and 1966, Justice Bose served as the president of the International Commission of Jurists. From 1959 to 1962, he also served as the national commissioner of the Bharat Scouts and Guides after being associated with the organisation for over four decades. During his last years, Justice Bose and Irene engaged in legal and cultural anthropology of the nomadic tribes in Nagpur.

Tenure at the Supreme Court in numbers

Figure 1 shows the number of judgements authored by Justice Bose during his Supreme Court career, and the number of benches he was a part of. In under six years, Justice Bose authored 124 judgements and was a part of 364 benches.

Justice Bose’s judgements dealt mostly with Criminal Law (51%), followed by Constitutional Law (23%) and Law of Evidence (7%).

Notable cases

In the Supreme Court

In State of West Bengal v Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952), a six judge bench of the Court struck down the West Bengal Special Courts Act, by a 5:1 majority. The legislation aimed to establish Special Courts to facilitate “speedier trial of certain offences.” From time to time, the state government would notify what offences could be classified as ‘special offences’. The majority found the law as violating Article 14 of the Constitution since the basis for the classification of offences was unclear, and the procedure under the Special Courts substantially differed from the general scheme.

Justice Bose, while agreeing with the majority, forwarded a unique perspective on Article 14. He stated that ‘classification’ was not the most correct test for equality. Instead, what was to be tested was if the “collective conscience of a sovereign democratic republic can regard the impugned law” as one that gives “substantially equal treatment.” Simply, he put forward that challenged laws must be tested on equality from the perspective of a fair, reasonable and unbiased mind. Some have argued that Justice Bose’s opinion in Anwar Ali Sarkar played a role in the acceptance of the ‘just, fair and reasonable test’ adopted 25 years later in Maneka Gandhi (1978).

In Rajnarain Singh v The Chairman, Patna Administration Committee (1954), a five-judge Bench unanimously upheld provisions of the Patna Administration Act, 1915 which was enacted to govern the newly developed areas of Patna city after the new province of Bihar was carved out of Bengal. The legislation empowered the local government to “extend to Patna the provisions of any section of the” Bengal Municipal Act, “subject to such restrictions and modifications” as deemed correct. Petitioners had challenged the Patna legislation on the ground that it substantially ‘modified’ the Bengal law while extending it. The Court ruled that as long as the ‘essential feature’ of the main law is not tampered, the modification is correct. Modifications could be at a local level, they ruled, and not alter the ‘legislative policy.’

Justice Bose, authoring the judgement, also provided a way to interpret differing opinions of judges in cases. In the case titled In re The Delhi Law Act, 1912 (1951), seven judges of the Court had given varying opinions on interpreting the words ‘restrictions and modifications.’ In Rajnaraian Singh, Justice Bose noted that in such cases, one needs to find the “greatest common measure of agreement” among the judges. In this case, the greatest common agreement among the judges in Delhi Laws Act was that there should be “very restricted” interpretation of ‘restriction’ and ‘modification.’

In the Nagpur High Court

In Bhagwati Chandra Shukla v. Provincial Government (1947), a Division Bench of the Nagpur High Court held that a press article did not violate Section 4(1) of the Press Emergency Powers Act, 1931 which punishes for “tending, directly or indirectly, to bring into hatred or contempt” the British government. The article accused magistrates, police and troops of the British government involved in the quelling of the 1942 uprising of “brutal repression, of killing, of shooting, rapes and murders.”

Justices Bose and S.W. Puranik noted that Section 4(1) was similar to Section 124-A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 which charges for sedition. They remarked that merely criticising the government or seeking to overthrow it by “constitutional means” was not seditious.