Justice In Circles

How architecture, history, and tradition inform the duality of Indian courts

From a distance, Indian courts present an imposing facade characterized by large domes, grand staircases, massive columns, and elevated pedestals. However, stepping closer, one can observe the differences in architectural features, motifs, dress codes, and imagery that reflect the unique interpretations of justice within these buildings. In her insightful essay, Rahela Khorakiwala emphasizes the importance of paying attention to the design of our courts. She argues that these architectural differences are not incidental but are deeply rooted in each court’s history and cultural influences. Drawing on extensive research, insider knowledge, and a critical eye, she invites readers to consider the intricate interplay between law, culture, and history that continue to shape our justice systems.

– Curator’s note by Snigdha Poonam

Standing in front of the Supreme Court of India in the heart of the national capital, one is struck by its circular dimension. The rotunda, under which the Chief Justice is seated, forms the centrepiece of its architecture.

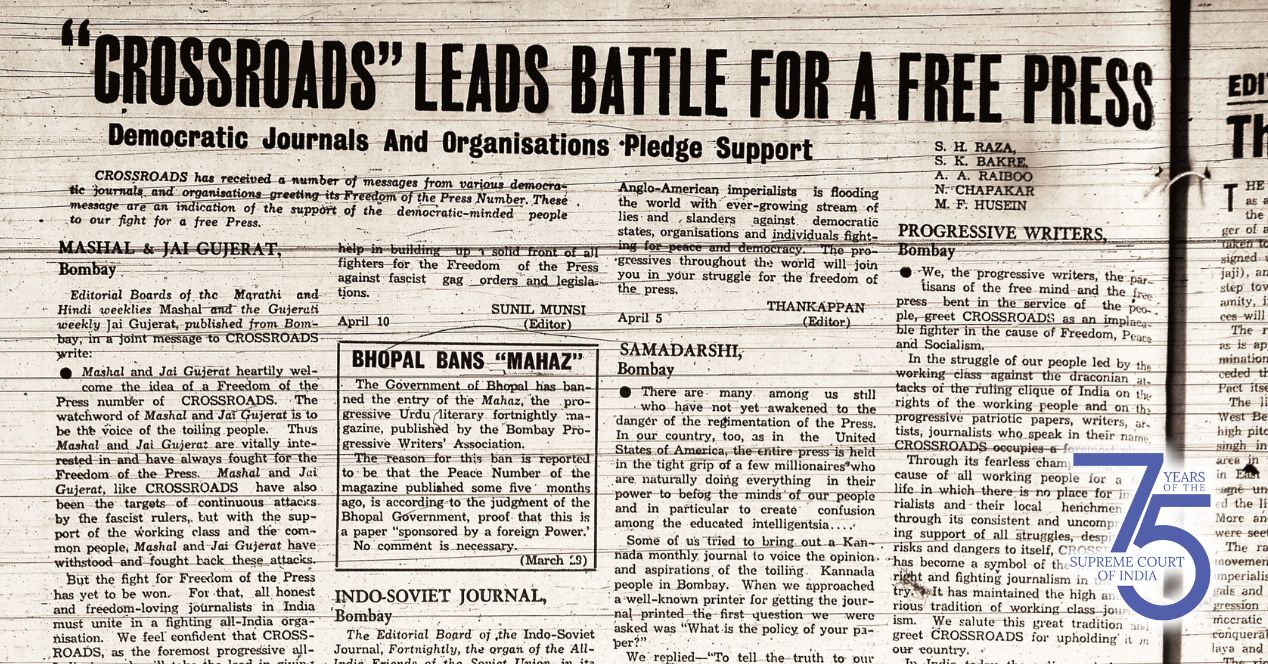

For most first-time visitors, this is the most compelling feature of its architecture—and one that has evoked many interpretations over the 75 years of its existence.

What does this circle stand for? In his article ‘In and Out of Court’, published in 1994, Piyel Halder argued that a circle in court architecture symbolises the control over “formlessness and chaos”. In the case of the Supreme Court of India, this geometric form signifies a sense of order amidst the diversity of people it represents, through mechanisms of judicial review, judicial activism and upholding of constitutional rights.

Today, in 2024, as we look back on the founding principles of the institutions that anchor the Indian republic, we see the circularity in all its complexities.

First, let us unspool the multiple rings of history that hold this circle in place. Prior to the formation of the Supreme Court of India, the Federal Court of India, established under the Government of India Act of 1935, exercised the authority to decide on cases already judged by the high courts.

This Court, operating out of the Princes’ Chamber of the old Parliament building between 1937 to 1950, was also a space for rulers of princely states to conduct negotiations with the British government about the extent of their autonomy post-independence.

From today’s perspective, the location would seem to threaten the very idea of separation of powers between the legislature and the judiciary that is embedded in the Constitution of India. What then did it mean for the independence of the judiciary when it was situated amidst the lawmakers?

The Supreme Court of India was moved to its present building in 1958. The chief architect was Ganesh Bhikaji Deolalikar, who was also the first Indian to head the Central Public Works Department (CPWD). The style he selected was the Indo-British style, in line with the aesthetics of Lutyens’ Delhi, a unique blend of local architectural elements and cultural traces representing colonial power. In doing so, Deolalikar made sure the structure reflected aspects of both colonial and post-colonial cultures.

The Supreme Court of India is built to represent the scales of justice. The central beam of the scales being the central courtroom, that is, the courtroom of the Chief Justice, flanked by the east and west wings on either side. These two wings represent the two scales of justice. The central courtroom is therefore always balancing the scales, and the delicate equilibrium between law and justice. As noted in a document of the Supreme Court Museum, the Court has at its very root the responsibility of balancing justice, “without inkling either to the right or to the left.”

The Supreme Court building is known for a distinctive set of architectural elements and iconography. It sits at a high pedestal, much higher than the level of the street—a feature Peter Goodrich says exists for most courts around the world and Piyel Haldar also documents this in his academic work. This assumed superiority through elevating positions continues in the courtrooms. The judges sit on an elevated bench and are significantly distant from the lawyers and litigants in the court. They are separated from all others by rows of benches, bookshelves, and the desks allotted to court assistants and stenographers.

Audibility is low and even with a mic system installed, no further than the front rows can hear the exchanges between the judges and lawyers. The litigants who are seated at the rear end of a large, crowded courtroom are often not privy to conversations about their own cases.

The Chief Justice’s courtroom is located beneath a large, dome-shaped ceiling, or rotunda, which brings us back to the geometric figure of the “circle”, a shape discussed by Haldar as important in legal architecture. His interpretation of the circle within a court is best described in his own words:

“This circularity, in its figurability, marks the principle of the absolute closure, of a return to unity and ultimate oneness, of a precise and faultless denial of the other; an omniscient model of truth that circumscribes the phenomenal world. It evokes the principles of perfection and since Pythagoras it serves to fictionalise the inner harmony of all matter, reflecting the circular movements of the universe and the natural process of birth, growth, decline, death, birth. As such, the circle seems to represent a defence against formlessness and chaos.”

The peculiarity of the Supreme Court’s circular design is further emphasised by its aerial view. From above, its structure has been interpreted by some as a “phallic architectural image”, reflecting entrenched male dominance within the court. This interpretation is underscored by the imbalance in the number of male and female judges appointed to the Supreme Court, to say nothing of the fact that in 75 years we have not yet had a woman Chief Justice of India.

The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 triggered changes in the administration of justice in British India which led to the establishment, in 1862, of the first three colonial high courts in the erstwhile presidency towns of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras. This system brought with it the common law form of jurisprudence, complete with its rich array of symbols, visual motifs, formal attire, and specific terminology. The legal system was largely based on precedents or judicial decisions made in previous cases, as practised in countries that were once part of the British Empire, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia.

At the time of the adoption of the Indian Constitution, these courts, along with their rules, practices and colonial culture were merged into the Indian legal system. Not only were the practices continued in the already established colonial courts, but they were also carried forward into the courts that were constructed post-independence.

In addition to adopting the common law form of legal system and continuing with British-drafted legislations (for example, the Indian Contract Act 1872, Indian Penal Code 1860), the customs and practices of British courts continued. That is, practices of wearing the wig, the white band, black robe, referring to judges as Your Lordship, bowing before the court, and the banning of photography within court premises.

Some of these elements are still deeply ingrained in the erstwhile colonial high courts. Although the Supreme Court of India was established after independence, it still occasionally adheres to colonial practices. This influence is most evident in the architecture of court buildings, the iconography of the statue of justice, and the enforced dress codes.

Architectural elements were among the primary tools used by colonial governments to assert their presence and authority. Constructing grand administrative and judicial buildings was a natural progression. Judicial iconography follows a similar pattern. According to Goodrich, courts are typically designed as imposing structures, raised above street level and featuring large, perpetually closed windows. The Supreme Court of India mirrors these colonial features in its design and layout.

A key symbol in judicial iconography is the statue of justice. Judith Resnik and Dennis Curtis have explored how various renditions of this statue and their interpretations differ in courts across the USA and globally. In India, the depictions of justice in colonial courts and their post-colonial adaptations reveal a blend of historical influences and popular culture.

In the Supreme Court of India, the idea of the statue of justice is rendered through a mural that is placed in the part of the court complex that requires permission to be accessed. The mural has Mahatma Gandhi on the left, the chakra in the centre, and a rendition of lady justice on the right. This statue of justice, in the form of a lady, is open-eyed, and dressed in classical Indian dance attire. She is holding the scales of justice in one hand, and her posture faces upwards, eyes looking to the scales. In the other hand she is holding a book, presumed to be the Constitution of India. The lady justice is placed atop a lotus flower, the national flower of India.

The prevailing image of the statue of justice, often seen in popular culture, typically portrays Justice as blindfolded, symbolising impartiality, and holding a sword, indicating the power to enforce law. In the movies, we often hear phrases like “justice is blind” (‘kanoon ke aankh pe patti hai’) or “there is rust on the sword of justice” (‘kanoon ke talwar pe jung lagi hai’). However, the depiction of the statue of justice in the Supreme Court of India diverges significantly. Here, justice is not blindfolded; she can see, suggesting an ability to discern right from wrong directly. Neither does she hold a sword. Justice, in this context, is meted out through the principles of the Constitution.

This imagery is open to multiple interpretations. A former judge, Justice M. Jagannadha Rao, draws a parallel to the deity of justice as described in the Vedic sutras. In his reading, this deity does not close its eyes but “allows the graceful rays flowing from its eyes to illuminate the administration of justice.” Justice Rao concludes that as per Indian tradition, the deity of justice has always had its eyes open, an attribute highlighted by the Sanskrit quotation “unmilya nethraschya”.

Judicial iconography, and its symbolism and interpretation, thus allows individuals to read the imagery through their own lenses. It enables the viewer to explore historical angles alongside their own contemporary understanding of the stories conveyed by court buildings. In my reading of the mural, there is an inherent conflict, between Indianised and Westernised notions of justice, a tussle between the colonial and post-colonial.

On one hand there is the need to place a “statue of justice” within the courts, an idea inherently Western. On the other hand, there is a compelling need to re-appropriate colonial culture and mark it as Indian. This is achieved by dressing the Western lady of justice in Indian attire and surrounding her by strong post-colonial symbols, such as the figure of inclusion of Gandhi in the mural.

These depictions of the statue of justice vary significantly between different high courts in India, reflecting a blend of Western influences and regional character. For instance, atop the Bombay High Court, a statue of justice is placed on a conical tower. The gender of this statue is ambiguous. It is not blindfolded and holds scales in one hand and a sword in the other. In contrast, the Calcutta High Court, completed in 1872, features carvings of the statue of justice as part of its original architecture. These carvings vary; some depict justice as blindfolded, while others show her with open eyes. This divergence within the same building illustrates the complex ways in which the concept of justice has been visually represented and interpreted in colonial-era court buildings across India.

Dress codes in courtrooms, particularly the traditional black robes and white bands worn by advocates, denote the courts’ reluctance to break with colonial traditions. Often compared to a magician’s gown, the black robe is said to endow advocates with an aura of unyielded powers and mystique as they navigate the corridors of justice. One judge from the Madras High Court humorously likened the appearance of advocates in their black gowns to bats flitting through the hallways. In Kerala, lawyers are often referred to as ‘vavval’, meaning bats.

My interviews with judges, lawyers and court staff in the colonial high courts of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras highlight the deep-seated importance they accord to the gown. Despite the hot and humid climate, the consensus was that the tradition of wearing gowns should continue, underscoring their integral role in maintaining the solemnity and decorum of the courtroom.

However, in response to the extreme temperatures, the Delhi High Court, which is a post-colonial institution like the Supreme Court of India, has routinely permitted advocates to forego wearing gowns during the summer months. Such a circular is in effect even today. This adaptation sparked a broader discussion, leading to petitions in the Supreme Court asking for a similar relaxation of the dress code during summer.

The first time around, in 2022, the Supreme Court directed the petitioners to approach the Bar Council of India, which is responsible for setting these dress code rules. In May 2024, a second writ petition has been filed which seeks, among other things, a Committee to be established at the central government level to look into the health and medical repercussions of wearing dark/warm clothes during summer months. The matter is yet to be heard.

The tragicomic scenario highlights the ongoing struggle between maintaining tradition and embracing practicality within our legal systems. It serves as another reminder that the relationship between Indian courts and their colonial origins is complex and nuanced. (While the iconic black gown is still a mandatory part of the attire in the Supreme Court and all high courts, it is optional in lower courts.)

As a precautionary measure during the Covid-19 pandemic, the Supreme Court asked advocates not to wear the black robe in virtual proceedings before it. With the lifting of Covid restrictions and court proceedings occurring in-person, this rule is not applicable anymore.

As the Supreme Court marks its 75th year, it could be an opportune moment for the institution to consider whether to further distance itself from some of its colonial legacies, including dress codes.

At this pivotal moment in India’s history, our courts face the challenge of carving a future that respects their heritage while shaping a justice system that is relevant and equitable for all Indians. On this balance hangs the future of the republic.

Dr. Rahela Khorakiwala is Assistant Professor at the BITS Law School and author of From the Colonial to the Contemporary: Images, Iconography, Memories and Performances of Law in India’s High Courts from Hart Publishers, 2020

Correction:

An earlier version stated that a new petition seeking the constitution of a committee to look into the repercussions of lawyers wearing dark/warm clothes during summer months was filed in June 2024. The petition was, in fact, filed on 27 May 2024. The error is regretted.