Analysis

A tale of two Chief Ministers

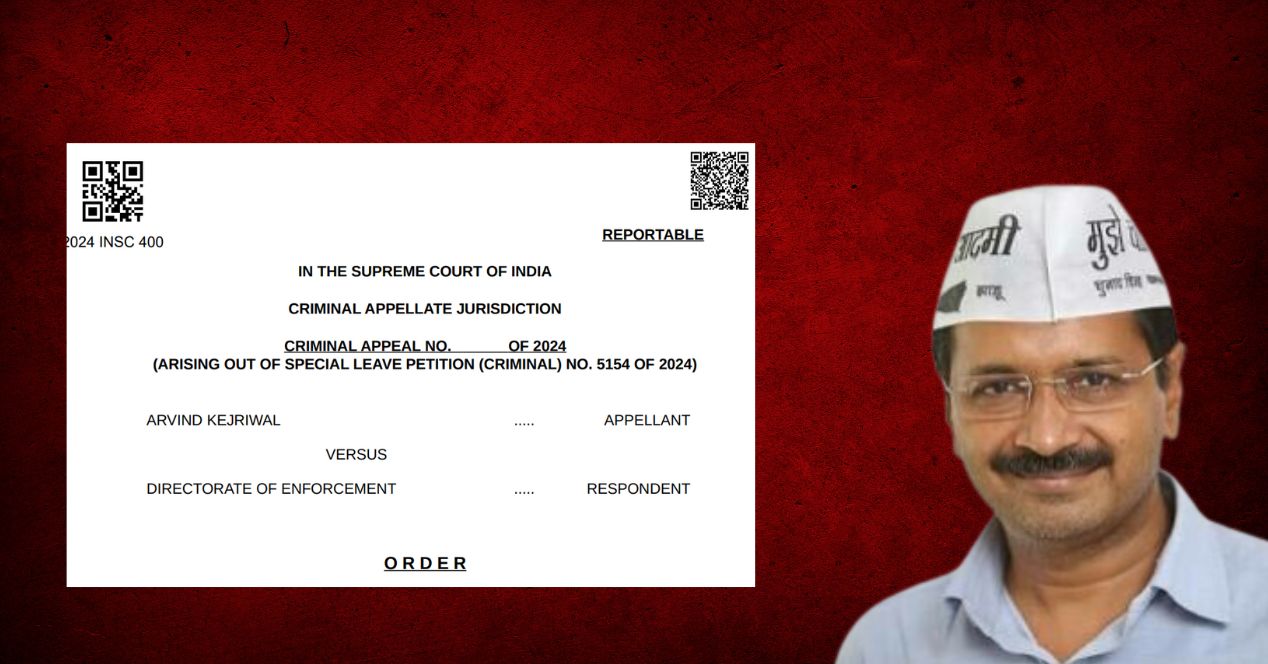

Arvind Kejriwal and Hemant Soren were both arrested by the ED in PMLA cases. Why did only one of them get interim bail to campaign?

The “Kejriwal order covers me,” declared Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal on 13 May 2024, while representing former Jharkhand Chief Minister Hemant Soren in the Supreme Court. Soren had been arrested by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) in connection with an alleged land scam. Sibal was referring to the interim bail granted just three days before to Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal, primarily so that he could campaign in the ongoing General Election.

Here were two chief ministers of Opposition-ruled states (Soren resigned just before his arrest). Both were arrested for alleged offences under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002. Both were arrested by the same central agency. Both contended that the arresting officer didn’t satisfy the PMLA condition of having sufficient “reasons to believe” the accused’s involvement. Yet, only Kejriwal was granted interim bail to campaign. Even as pockets of Jharkhand are left to vote in the sixth and seven phases of the election, Soren remains in jail.

Naturally, Opposition parties placed the cases in the same bucket—they called out the Bharatiya Janata Party for politically motivated arrests. Observers have reacted to this situation with bafflement. How did the two cases have different outcomes? The answer became clear as the proceedings unfolded.

Soren’s case turned on a cognisance order that had already been issued by a Special Court, dedicated to hearing PMLA cases. A cognisance order is when a court takes note of an offence, based on evidence gathered during investigation. It precedes the start of a trial. A court is yet to take cognisance of any alleged offence by Kejriwal. In fact, it was only last week that the ED filed a supplementary chargesheet naming Kejriwal as an accused in the excise policy case.

While Soren went to the Supreme Court claiming that the arrest was unlawful, he had also approached the Court separately seeking interim bail. Kejriwal had made it clear to the Court that he wasn’t seeking bail because that would legitimise his arrest.

In a bail petition, Kejriwal would have to prove that he was not guilty of the offence. But in the plea challenging arrest, the burden was on the ED to convince the Court that Kejriwal’s arrest was justified. (The idea of ‘interim bail’ was suggested by the Bench, citing the elections and lengthy hearings in Kejriwal’s plea.)

Further, Kejriwal was arrested in March, after the Model Code of Conduct had already kicked in. This factored into the Court’s decision of granting interim bail until polling concluded. Soren was arrested in January, and the Special Court had already rejected his bail petition.

On Wednesday this week, the Court not only refused to hear Soren’s plea, it even observed that Soren had approached the forum with “unclean hands.” A vacation bench led by Justices Dipankar Datta and S.C. Sharma highlighted Soren’s omission of the cognisance order in the list of dates that was filed with his plea in the Supreme Court. Justice Datta also censured Soren for pursuing bail in both the trial court and Supreme Court.

Sibal clarified that his plea was not of bail but of release. The submission was unexpected as Sibal had earlier sought interim bail for Soren while relying on the Kejriwal order. He argued that the cognisance order was irrelevant as it was issued two months after Soren was arrested—his plea was restricted to the validity of the arrest.

But the Bench had made up its mind, even wanting to place on record that Soren had tried to conceal facts. To avoid such an inglorious dismissal, a deflated Sibal withdrew the plea. That’s how this round of Soren’s legal battle ended in the top court, with Sibal having to accept that the Court had no inclination to take the “holistic and libertarian view” it did in Kejriwal’s case.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!