Analysis

Kejriwal’s interim bail lays the ground for a ‘public interest’ argument in personal liberty cases

The Delhi CM’s release to participate in campaigning suggests that the operation of special laws must meet constitutional parameters.

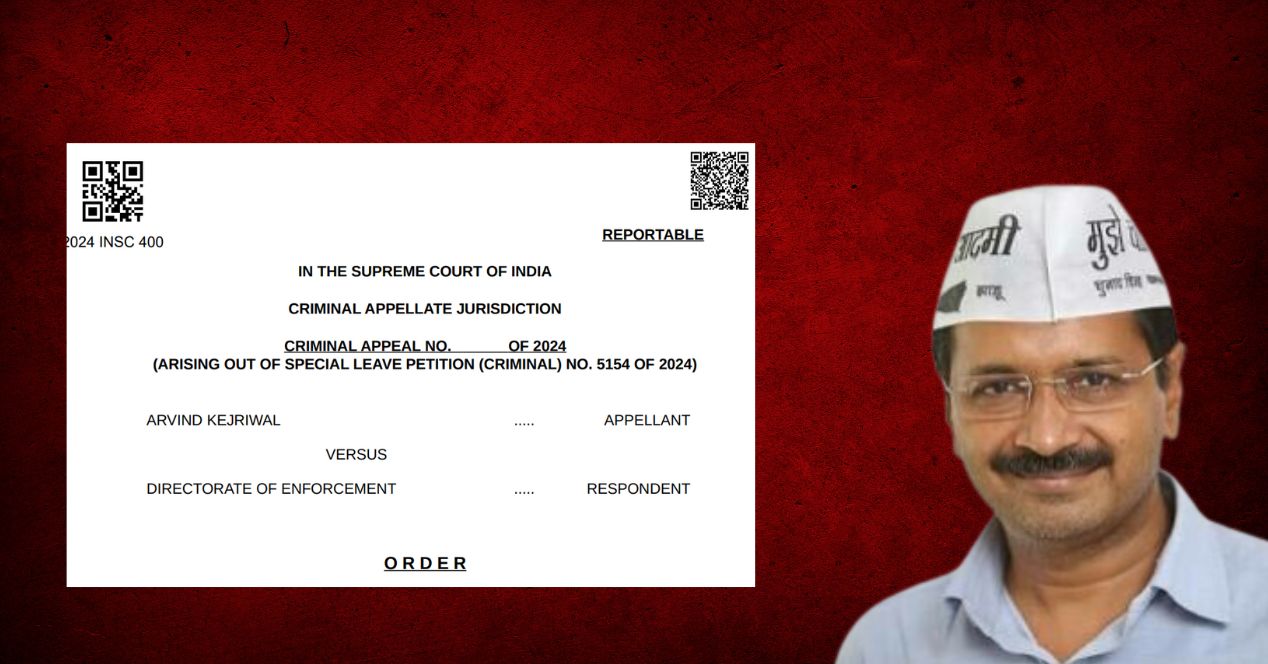

It is not every day that extraordinary relief is granted to an Opposition leader in a legal tussle with state agencies—that is the prevailing sentiment surrounding the interim bail granted by the Supreme Court to Delhi’s Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal.

Indeed, the relief warrants some analysis for how extraordinary it is, but I also want to take this opportunity to examine the legal framework of bail conditions.

The grounds for release are unique

With regard to the grant of interim bail, the Order relies on earlier precedents which have held that although “interim bail” is alien to statutory provisions, it can be traced to Article 21, as a judicial tool to do complete justice and protect personal liberty in appropriate cases. Conceptually speaking, interim bail is not new or revolutionary, and the relief is granted in many cases based on factual circumstances.

Most often, it is seen in cases where undertrials need medical intervention which is not possible in jail, or for attending marriages and other family functions. In fact, in Para 14 of the Order granting Kejriwal interim bail, the Supreme Court categorically reminds us that this is not an exception carved out for this case, and is very much a part of the routine rigmarole of bail applications.

What makes Kejriwal’s interim bail unique is the ground on which he is being released. Here’s how the Supreme Court put it in its Order:

“It is no gain saying that General Elections to Lok Sabha is the most significant and an important event this year….General Elections supply the vis viva to a democracy. Given the prodigious importance, we reject the argument raised on behalf of the prosecution that grant of interim bail/release on this account would be giving premium of placing the politicians in a benefic[ial] position compared to ordinary citizens of this country.”

I say the reason is unique because the need to release the accused on interim bail does not stem from arguments qua his liberty or his statutory rights or customary duties, but from a public interest defence against incarceration in the midst of a General Election.

While the Enforcement Directorate (ED), speaking through some of the government’s leading law practitioners, argued against recognition of any special right including a “right to campaign” as being violative of Article 14 of the Constitution, the agency failed to address the pressing perspective which weighed on the judges.

Special statutes should not operate in a constitutional vacuum

The issue, then, was never whether Kejriwal’s right to campaign outweighs the agency’s right or the mandate of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 to keep him in judicial custody. If the Court had limited itself to determine whether Kejriwal was entitled to certain rights which warrant his release, surely the outcome could not have been to grant interim bail, as no politician would otherwise serve jail time in a country where there are polls or by-polls happening almost every other month.

In my reading of the Order, there is a cogent and consistent substratum to the discussion, which is to recognise that an incarceration of a national political leader which prevents them from participating in the Lok Sabha election campaign could undermine the federal and democratic framework of the polity and Constitution.

Kejriwal has not made out a case to be released on interim bail. The strength of the case to release him comes from the need to add sanctity and credibility to the democratic electoral process. Criminal law and procedure, as exclusive as it may seek to be in the operation of special laws, must always meet constitutional parameters, even if the Court is deciding on the mere issue of interim bail.

By recognising that the release on interim bail would be a necessary step towards furthering democratic principles, the Supreme Court has, in my view, laid the groundwork for development of a public interest argument in favour of bail and interim bail. This approach is opposed to the traditional view of determining whether the accused deserves discretionary relief on the basis of his personal circumstances. Time will tell whether this argument develops further in bail jurisprudence in India.

Reasoning for interim bail conditions is undercooked

That brings me to the conditions imposed for granting the relief. Bail conditions are not statutorily prescribed either in the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 or in the PMLA. It’s left to judges to impose conditions that are seen as necessary for the advancement of justice and to ensure there is no interference with investigation or trial. There must be some nexus between the condition imposed and the interest of the trial or investigation, without which the discretion runs the risk of being arbitrary.

In a case where fact-checker Mohammed Zubair was incarcerated for tweets he had put out, the state of Uttar Pradesh had argued that he must be barred from tweeting as a condition for release. There, a three-judge Bench led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud rejected the submission of the state to hold that “the bail conditions imposed by the Court must not only have a nexus to the purpose that they seek to serve but must also be proportional to the purpose of imposing them.” Conditions that resulted in the “deprivation of rights and liberties must be eschewed,” the Supreme Court said. (Disclaimer: I had represented Zubair in the matter.)

In Kejriwal’s case, the ED’s arguments on bail conditions were premised largely on preventing him from participating in politics and governmental decision-making. The agency made little to no endeavour to demonstrate why such conditions were necessary for proper investigation and trial in the PMLA case in which Kejriwal has been arrested.

Unfortunately, the Bench let this pass. While its Order cited precedents to hold that it would not be proper to impose conditions that deny Kejriwal the right to participate in electoral politics as the same may be an unreasonable restriction of fundamental rights, it didn’t provide any reasoning for the conditions that Kejriwal shall not visit the Delhi Secretariat or attend his office as Chief Minister.

The Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR)—the formal entry of complaint by ED—in the case was registered on 22 August 2022 and the first prosecution complaint was filed on 26 November 2022. Since then, four supplementary prosecution complaints have also been filed. In the circumstances, it’s fair to assume that all necessary documents and papers have been seized and are in the ED’s custody. It is nobody’s case that visiting the Secretariat or the Chief Minister’s office could lead to any kind of tampering of evidence.

Given that the conditions have no nexus to proceedings, observers may perceive this part of the decision to be a balancing act. The lack of reasoning behind the bail conditions is perhaps an overkill to balance the extraordinary relief granted. Whether Arvind Kejriwal should continue to function as the Chief Minister after his arrest is a political decision, and one that has no impact on the fairness of investigation and trial under the PMLA.

Yet, not many will be complaining about the bail conditions at this point in time. Only grumbling students of the law such as myself actively look for reasons in the exercise of discretion while imposing bail conditions. Most others are understandably celebrating the interim triumph of personal liberty and electoral fairness, at least for three summer weeks.

Soutik Banerjee is a Delhi-based advocate. He practises in trial and appellate courts.