Analysis

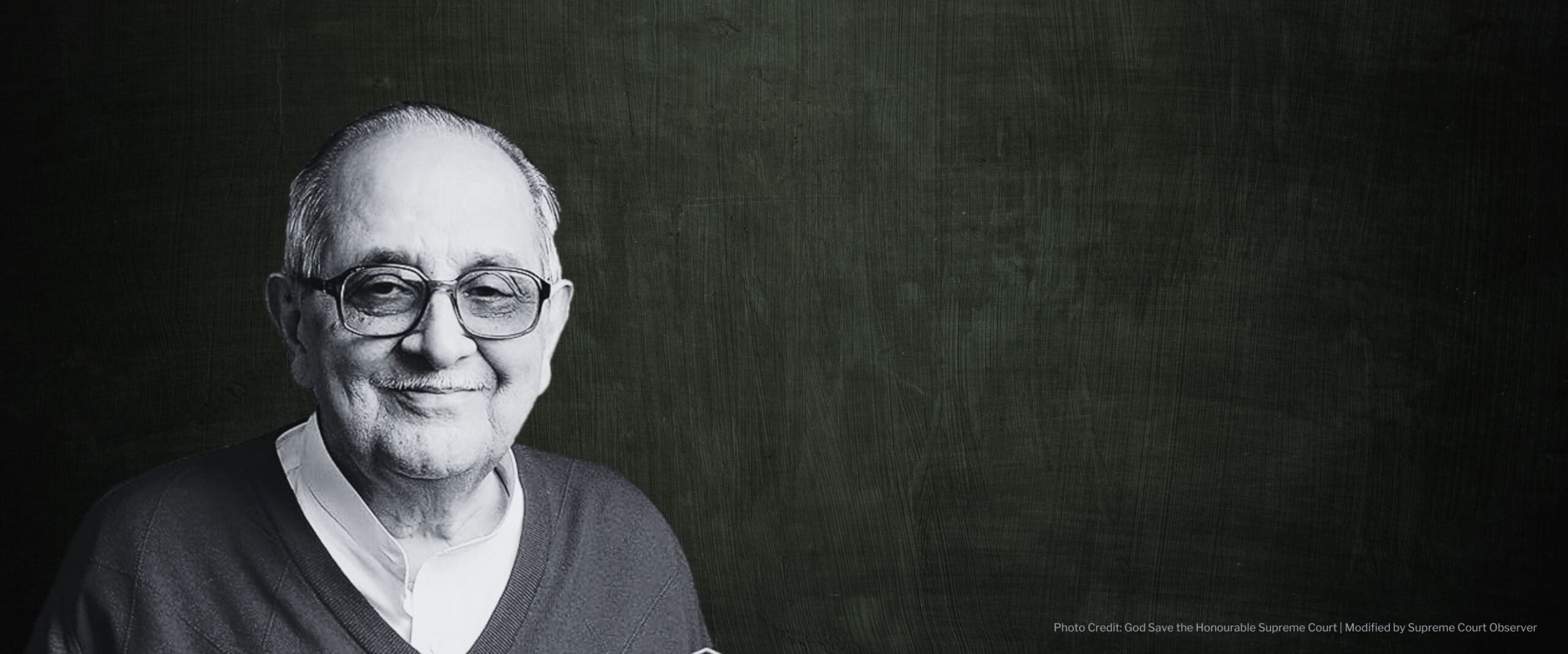

Farewell Fali

A tribute to Fali Nariman, a commercial lawyer from Bombay who became one of India's finest constitutional law advocates

Everybody and his uncle has been narrating a Fali Nariman anecdote. The idiom is literal in my case. My uncle’s story is from when Nariman was a parliamentarian. He couldn’t appear in court but he’d agreed to provide friendly advice on an intellectual property matter at the request of the chairman of a large company.

My uncle, who worked for the company, reported to the famous Hauz Khas address on a chilly Sunday afternoon. He was accompanied by a battalion of company men, advocates and bundles of case papers. After a short briefing, Nariman had only one question: could he be shown the affidavit where a particular contention had been made? It set off a frantic scramble to extract the document from the bundles.

It didn’t take long for Nariman to lose his patience and walk out. When they found the correct affidavit, my uncle scampered after Nariman. “It’s all very well to tell me,” Nariman said, “but why didn’t you tell the court?” But they had told the court, my uncle said.

“Are you sure? Then only God can save you.”

Even in the universe of Fali Sam Nariman, there were certain things from which only God could save you, including the lack of collegiality among Supreme Court judges (He wrote a book titled God Save the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the year of the infamous press conference.)

My uncle’s anecdote showcases Nariman’s impatience but also highlights his extraordinary ability to get to the heart of a legal issue from the morass of paperwork and dithering briefers. This skill made him one of India’s finest constitutional law advocates. His clear-eyed submissions and focus on reliefs stood out in a field often crowded with appeals to vague notions of justice.

Even his defence of the basic structure, a doctrine which he wrote had “evolved from the great silences in our Constitution”, was grounded in matter-of-fact: “illogical” but an “auxiliary precaution against a possible tidal wave of majoritarian rule.”

In Delhi, a city where, in his own words, “loyalties are most ephemeral,” this Bombay Parsi’s constancy in personality was striking. No matter which way the political wind blew, you’d be sure to hear from Nariman, flying the flag for fundamental rights, immune to the lures of high office.

His late wife Bapsi had complained that he accepted the post of Additional Solicitor General “too easily” from Indira Gandhi’s government in the early 1970s. But he resigned just as easily when the Emergency was declared. Decades later, he returned the file on the Narmada Dam rehabilitation case to the Gujarat Government when he heard about attacks on Christian tribals in Dang district.

Nariman was the rare public figure who was level-headed about the Indian judiciary. He divided judges into three categories: ones with a political agenda, ones with a social one, and ones with no agenda. Most Indian judges, he felt, fell into the third category, and the judiciary was better for it. Nariman’s formula for the ideal mix in the higher judiciary was “three-quarters problem-solvers and one-quarter crusaders.”

He lauded and criticised the work of the Supreme Court, but didn’t rely on the partisan-based frameworks of American Supreme Court analysis. As recently as November 2023, he told a magazine that he didn’t think that the Supreme Court was “working under political pressure” and, in fact, “was trying to further the aims and objects of the Constitution.”

He died with his boots on, as he wished. In his last week, he was reportedly working on a Constitution Bench matter and had dashed off letters to the winning counsel in the electoral bonds case.

There was no grandstanding with Fali Nariman. Yet, this week, all the grand have been standing in tribute. A great champion of the rule of law is gone.

This article was first featured in SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!