Analysis

A Classroom Discussion on Criminal Reform Comes Alive in the SC

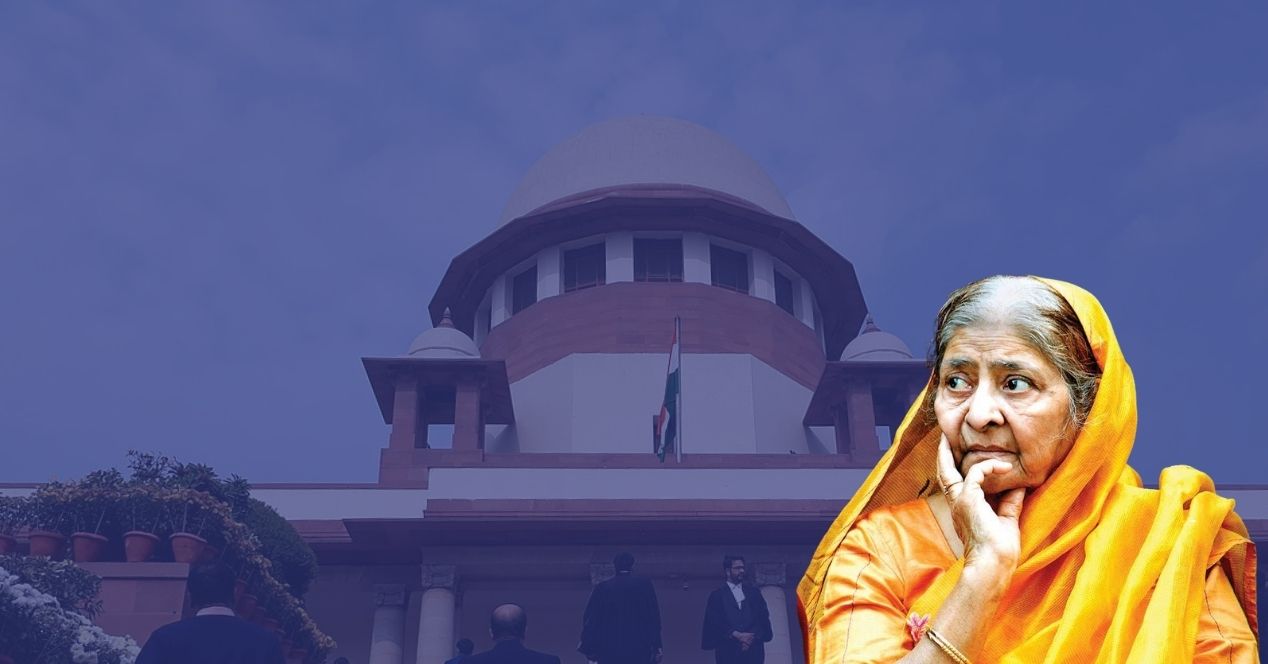

DESK BRIEF: The Bilkis Bano Convict Remission case has exposed the gap between theory and practice in criminal justice administration

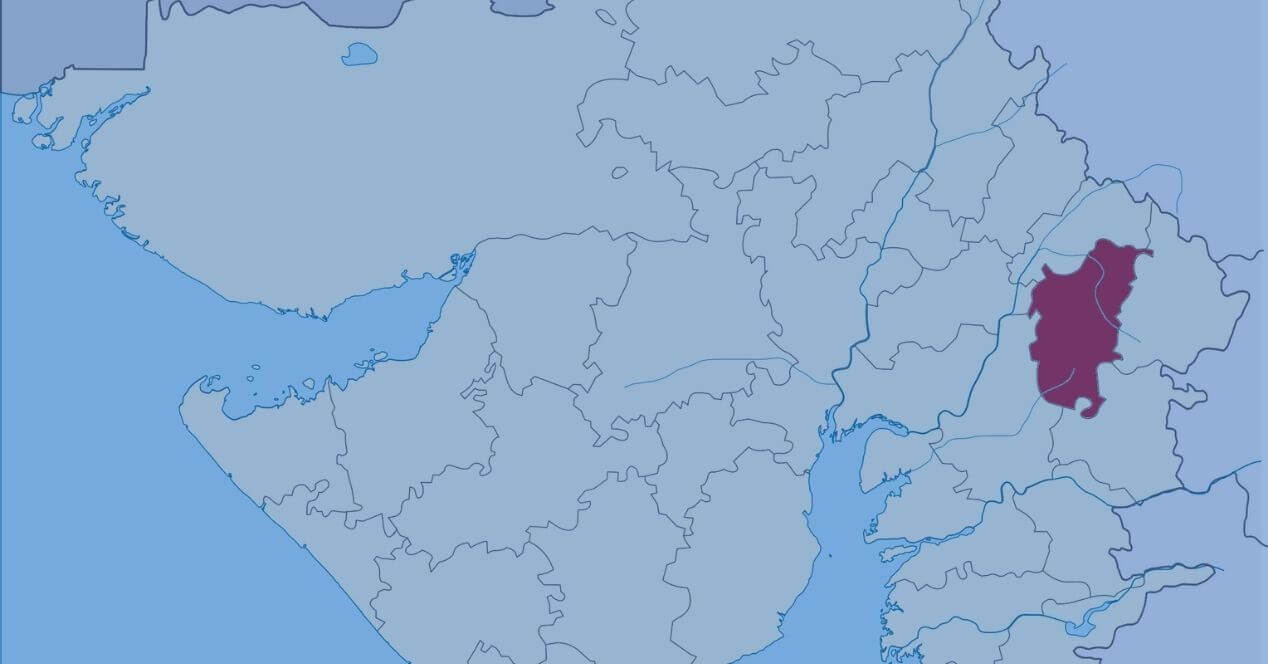

In 2008, a trial court convicted 11 offenders for the rape of three women and the murder of seven individuals during the Gujarat Riots. One of the raped women was Bilkis Bano, who was pregnant at the time. One of the murdered individuals was her three-year-old daughter. In 2022, the convicts were released under the Gujarat Remission policy, on account of having served 14 years of a life imprisonment sentence and by satisfying the “good behaviour” criterion.

Through August, I’ve been reporting on the Supreme Court hearings challenging the remission granted to the convicts. And what I’m seeing playing out is both a philosophical and interpretative battle about criminal justice administration in the country: over what it is, and what it should be. It’s brought alive the debate we used to have within the jurisprudence classroom: deterrence versus reformation. Only, in the rough and tumble of governance and court practice, things often don’t fit into neat categories. There are qualifications, adjustments, and compromises to deal with.

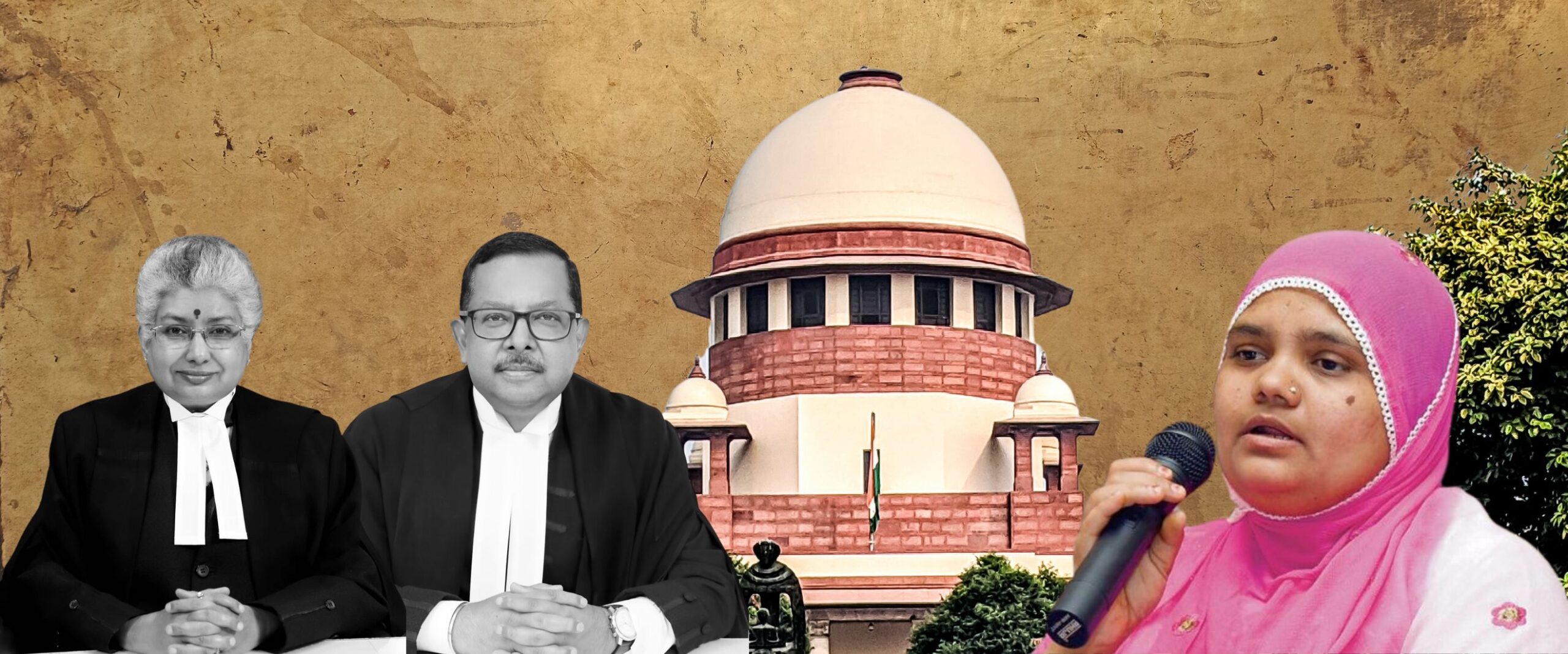

Before a bench of Justices B.V. Nagarathna and Ujjal Bhuyan, the Gujarat government’s lawyers argued that the remission fit into the larger goal of the criminal justice system: reformation. The convicts, they contended, deserved a chance to reintegrate with society.

The case has also laid bare the tension between the executive and the judiciary when it comes to sentencing. Conviction is a judicial function but remission is an executive one: provisions of the Constitution and the CrPC enable the President of India, the Governor of a state, and any state government to consider remission.

But this cut and dried distinction has been disputed by the Supreme Court itself in Swamy Shraddhananda v State of Karnataka (2008). Here’s what Justice Aftab Alam observed there:

“Once the judgement is signed and pronounced, the execution of the sentence passes into the hands of the executive and is governed by different provisions of law. What is the surety that the sentence awarded to the convict after painstaking and anxious deliberation would be carried out in actuality?”

In Union of India v Sriharan (2016), a Constitution Bench deliberated whether an offender can be convicted of life imprisonment till their “last breath”, without the option of remission. This “special sentence” was endorsed by a three-judge majority who viewed it as an “alternate punishment” to the death penalty. Former Chief Justice U.U. Lalit, one of the dissenters, argued that alienating the possibility of remission “closes doors for reformation.” Since the “special sentence” is not found in any statute books, he felt it “encroaches upon powers of the legislature.”

Justice Alam’s decision in Shraddhananda provided a possible bridge between cup and lip: he noted that the special sentence was needed because remissions were being granted in “an unsound manner.” But that’s as far as he went—the Court didn’t dwell on a specific definition of what could constitute “unsound.”

Arguing on behalf of Bilkis Bano, Advocate Shobha Gupta emphatically suggested that the Gujarat government had failed to consider the “heinous nature” of crime.

The hearings are not yet complete, but it is clear that the Court has an opportunity to develop the jurisprudence around reformative justice by clarifying what it means for the executive to issue a remission in an “unsound manner.” Are convictions for a certain class of crimes meant to have a deterrent effect? Does time, context, and heinousness matter? Perhaps the decision will muddy the discussions in future jurisprudence classes at law schools around the country, but that will make it a lot more like life.

This article was first featured on SCO’s Weekly newsletter. Sign up now!

Subscribe!