The First Eight

As part of our special series on the Supreme Court’s 75th anniversary, we take a brief look at the lives and times of the first eight judges

The Supreme Court at 75 is a well-oiled machine. Its 34 judges have a vast library of precedents to rely on and time-honed processes to ensure smooth functioning. There’s a playbook for procedures like appointments and elevations, and day-to-day operations are managed by a Registry that can fall back on institutional memory.

But what was it like in the early days, when the ink on the Constitution was still wet? Back then, the sanctioned strength of the Court was just eight. Six judges were present in the Court’s inaugural session on 28 January 1950: Chief Justice Harilal Kania, and Justices S. Fazl Ali, Patanjali Shastri, Mehr Chand Mahajan, B.K. Mukherjea, and S.R. Das. Justice N.C. Aiyar was appointed in September 1950. A year later, Justice Vivian Bose came on board to complete the original roster of eight.

Some judges in this ensemble had things in common. Two of them were knighted, three were barristers educated in London, half of them came from upper-caste, affluent Hindu families. Almost all of them went on to have administrative careers after their time at the Court and five of them became Chief Justice.

But their individual stories reveal many differences. There was representation from four regions and three religions. Their early lives and trajectories had played out somewhat differently; the areas of interest and expertise, too, differed.

Here, I’ve put together potted introductions of the ‘original eight’. The idea here is to distill the lives and legacies of the judges to convey their contribution to the nation-building exercise of a young republic.

I owe a debt to George Gadbois, whose seminal work I have drawn liberally from. Judges of the Supreme Court of India 1950-80, first published in 2011, was one of its kind—based on over 116 interviews with more than 66 judges and numerous lawyers, politicians and court staff. It offers more than a tantalising glimpse into the backstage of the Court’s functioning and captures details of the inner lives of the judges in a novel manner.

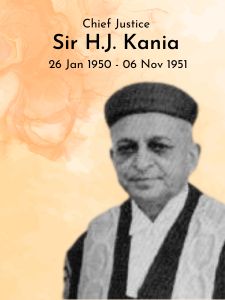

Chief Justice H.J. Kania: First among equals

Sir Harilal Jekisondas Kania was the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and its predecessor the Federal Court in independent India. In those early years, it was up to Kania to ensure that the Union government curbs its centralising tendency and respects the federal scheme of the newly formed democratic republic.

Sir Harilal Jekisondas Kania was the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and its predecessor the Federal Court in independent India. In those early years, it was up to Kania to ensure that the Union government curbs its centralising tendency and respects the federal scheme of the newly formed democratic republic.

He had a somewhat fraught relationship with the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who understandably took a great interest in the affairs of the Supreme Court. The two didn’t see eye-to-eye on judicial appointments, with Kania being wary of interference by a powerful executive.

Kania’s blocking of appointments in the Madras High Court and the Rajasthan High Court had also earned Sardar Patel’s displeasure. The tension intensified after early decisions of the Kania-led Court in free speech cases like Romesh Thapar v State of Madras (1950) and Brij Bhushan v State of Delhi (1950). In response, Parliament extended the ambit of reasonable restrictions on fundamental rights via the First Constitutional Amendment.

Read more about his life and career here.

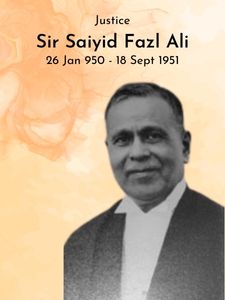

Justice S. Fazl Ali: From London to Delhi via Chapra

A seventh-generation lawyer hailing from Varanasi, Sir Saiyed Fazl Ali was educated at Muir Central College and later studied law at London’s Middle Temple, becoming a barrister in 1912. He returned to India and began practising in the trial courts of Chapra in Bihar, an unusual professional choice for a barrister at the time. In 1943, he became the first Indian Chief Justice of the Patna High Court.

Fazl Ali was frequently called upon to resolve difficult disputes, including industrial disputes in Jamshedpur. He also sat on the Royal Indian Navy Mutiny Inquiry Commission, which had been established at a particularly sensitive moment in the freedom movement.

Notably, Fazl Ali was in dissent in some of the most critical cases heard and decided by the Kania Court. These included landmark cases on the freedom of press—Romesh Thopar and Brij Bhushan. In both these matters, he found that ensuring ‘public order’ was subsumed under the reasonable restriction of ‘security of state’ and was reason enough to censor publications. It was an influential view. Not long after, the first Constitutional Amendment added the words ‘public order’ to Article 19(2).

After retirement, on Nehru’s request, he served as Governor on two occasions—for the states of Orissa and then Assam. Controversially, he was still a judge when the role of Governor of Orissa was offered to him. He was also the Chairperson of the States Reorganisation Commission.

Read more about his life and career here.

Justice M. Patanjali Sastri: The second-in-command

Like Kania, Sastri was also from a family of Sanskrit scholars. Born in Madras, Tamil Nadu, Sastri went on to become the first judge to be appointed to the Supreme Court who was not a judge of the erstwhile Federal Court. He was known for his expertise in tax law.

Like Kania, Sastri was also from a family of Sanskrit scholars. Born in Madras, Tamil Nadu, Sastri went on to become the first judge to be appointed to the Supreme Court who was not a judge of the erstwhile Federal Court. He was known for his expertise in tax law.

Landmark cases that Sastri sat on include the likes of Chiranjeet Lal Chowdhuri v Union of India (1950) and Champakam Dorairajan v Union of India (1951). The former was about the constitutionality of a law that was enacted to manage the affairs of a specific company—the Sholapur Spinning and Weaving Company Limited. Justice Sastri’s dissenting opinion held that the law was violative of Article 14, since it imposed “burdens and disabilities” on a single company and its shareholders without any “reasonable classification”.

Sastri was India’s second Chief Justice. During his two-year tenure, he was responsible for the appointments of four judges.

In a way, Sastri’s appointment as Chief solidified the convention of the senior-most judge of the Court becoming the CJI. There’s a strong rumour that when Kania died in office, Nehru did not want Sastri to take his position—his preferred candidates included M.C. Chagla from the Bombay High Court and S.R. Das (who was fourth in line based on seniority). The prime minister relented only when the six sitting judges threatened to resign if the seniority convention wasn’t followed.

Read more about his life and career here.

Justice Mehr Chand Mahajan: Advisor to princes

Pending before the Supreme Court currently is an Original Suit filed by the state of Maharashtra. The ask—ownership over the Belagavi region. The district with a Marathi-speaking majority was made a part of the State of Mysore (now Karnataka) on the recommendation of the States Reorganisation Commission, led by Justice Fazl Ali.

Pending before the Supreme Court currently is an Original Suit filed by the state of Maharashtra. The ask—ownership over the Belagavi region. The district with a Marathi-speaking majority was made a part of the State of Mysore (now Karnataka) on the recommendation of the States Reorganisation Commission, led by Justice Fazl Ali.

One of the key documents relied on by Karnataka in this matter is a report of a single-member Commission composed of Justice M.C. Mahajan. Even as he is best remembered for this report, he had his finger in many pies. Before he became a judge, he was an illustrious lawyer and even served as Prime Minister of Jammu & Kashmir. After retirement from the Supreme Court, Mahajan took on assignments as varied as being on the board of Delhi Cloth and General Mills to being a member of the Camp College Enquiry Commission, which was established to address the needs of refugees from Punjab.

Mahajan was the third Chief Justice but he had taken on several compelling assignments before his stint in the Supreme Court. He was sought after by the princely states as a legal advisor. Apart from his stint as Prime Minister of J&K, he provided legal counsel to the Maharajas of Chamba and Bikaner. His knowledge of Urdu meant that he was on a special bench in Hyderabad that was tasked with disposing matters that had been transferred to the Supreme Court after the Nizam’s Privy Council was wrapped up in 1950.

Even his hobbies helped him stand out from the rest of the pack. Mahajan was an avid horticulturist and was elected President of the All-India Fruit Producers Association in 1945.

Read more about his life and career here.

Justice B.K. Mukherjea: The scholarly hustler

The first Supreme Court judge from West Bengal, Mukherjea came from a high-caste but not well-to-do family. He was celebrated for his research and also won several medals and awards for his writings. This included gold medals at the University Law College in 1914 and 1916. He had as many as five degrees, including in Sanskrit, History and Law.

The first Supreme Court judge from West Bengal, Mukherjea came from a high-caste but not well-to-do family. He was celebrated for his research and also won several medals and awards for his writings. This included gold medals at the University Law College in 1914 and 1916. He had as many as five degrees, including in Sanskrit, History and Law.

In January 1914, at the age of 22, he began his legal career as an advocate at the Calcutta High Court. To overcome his financial hardships, he worked as a part-time lecturer.

He was appointed as a judge of the Calcutta High Court after two decades of practice. Close to nine years of service there made him the first Bengali to be elevated to the Federal Court in 1948. He was a chartered member of the Supreme Court and went on to become India’s fourth Chief Justice.

His tenure as Chief Justice was disturbed by heart ailments, and eventually ended prematurely.

Read more about his life and career here.

Justice S.R. Das: Guardian of a larger court

Das was born in an affluent family of lawyers and politicians. After earning a degree in law in London, he returned to India to practise at the Calcutta High Court in 1919. He was elevated to the Calcutta High Court in 1942. In 1949, he was appointed as Chief Justice of the High Court of East Punjab.

Das was born in an affluent family of lawyers and politicians. After earning a degree in law in London, he returned to India to practise at the Calcutta High Court in 1919. He was elevated to the Calcutta High Court in 1942. In 1949, he was appointed as Chief Justice of the High Court of East Punjab.

He was appointed as a judge to the Federal Court just a week before it was replaced by the Supreme Court. He was the only judge amongst the original eight to serve the entire decade at the top court.

His decisions showcased his commitment to protecting individual rights and freedoms. His dissent in State of Bihar v Kameshwar Singh (1952) declared that the requirement of “public purpose” and compensation in land acquisition cases is inherent in Article 31(2). He reiterated this stance in Raja Suriya Pal Singh v Uttar Pradesh (1952), while rejecting the arguments of one Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who was appearing for a batch of zamindars from Uttar Pradesh.

He became India’s fifth Chief Justice in 1956, following Mukherjea’s untimely resignation. Some of his administrative decisions during his tenure had lasting implications. For one, during his tenure, the Court’s strength increased from eight to eleven judges. Six of the ten judges he appointed went on to serve as Chief Justice between 1964 and 1971.

After retirement, he served as vice-chancellor of Visva Bharati University. In 1961, he chaired the Punjab Commission, which was set up to collate the grievances of the Sikh community. In 1963, he was appointed by the Home Ministry to inquire into allegations of corruption against Pratap Singh Kairon, the Chief Minister of Punjab.

Read more about his life and career here.

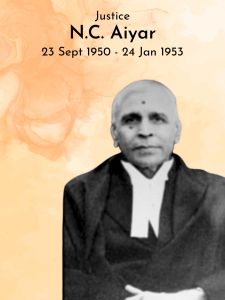

Justice N.C. Aiyar: Sessions to Supreme Court

Nagapudi Chandrasekhara Aiyar came from a family of Sanskrit scholars in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh. He entered office in September 1950, the first judge to be appointed after the Constitution came into effect. He was also the first judge of the Supreme Court who started his judicial career from the subordinate courts.

Nagapudi Chandrasekhara Aiyar came from a family of Sanskrit scholars in Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh. He entered office in September 1950, the first judge to be appointed after the Constitution came into effect. He was also the first judge of the Supreme Court who started his judicial career from the subordinate courts.

He practised at the Madras High Court for 17 years before joining the judicial service as a city civil judge. He later worked as a district and sessions judge. This eventually led to his elevation to the Madras High Court in 1941. When he came to Delhi in September 1950, Aiyar was 63.

He retired in 1953 but was called in to serve the Court twice when Chief Justice Mukherjea fell ill in 1955. After his final departure from the Court at the age of 68, he chaired the First and Second Delimitation Commissions, which had been tasked with redrawing the map of elector constituencies in the wake of the states’ reorganisation.

Read more about his life and career here.

Justice Vivian Bose: The last link

Vivian Bose, the final member of the ‘original eight’, was sworn in to the Supreme Court on 3 September 1951. With an Indian father and an English mother, Bose was the only Christian and Eurasian judge at the Court. His wife was American author and social worker Irene Mott. Her father, John Mott, was a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

Vivian Bose, the final member of the ‘original eight’, was sworn in to the Supreme Court on 3 September 1951. With an Indian father and an English mother, Bose was the only Christian and Eurasian judge at the Court. His wife was American author and social worker Irene Mott. Her father, John Mott, was a Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

Before his stint at the Supreme Court, Bose was the Chief Justice of the Nagpur High Court. During this time, he presided over two significant tribunals: the Bilaspur Commission of Inquiry in 1938, which investigated election malpractices and the Hill Investigation Tribunal in 1940.

Educated at Cambridge, Bose was known for his eloquence and command over the English language.

After retiring on 9 June 1956, he was called back to service just a year later by Chief Justice S.R. Das, under Article 128. During his second tenure, Bose chaired two significant inquiry commissions. The first investigated the Mundhra scandal, involving a Calcutta industrialist’s collusion with the Life Insurance Corporation. His report alleged a quid pro quo between Mundhra and the Congress government, prompting a rift with Prime Minister Nehru. The other inquiry Bose led was the Dalmia-Jain Commission, which probed alleged improprieties by two industrialists.

Bose had many interests outside court, including riflery, motoring and magic.

His death in 1983 marked the end of an era. The last connection to the Supreme Court’s original bench had been severed.

Read more about his life and career here.