Celebrating 75 years of the Supreme Court

In the 75th year of the Supreme Court, we are introducing a special series showcasing the institution through a cultural and critical lens

The ornate, wood-panelled interiors of the Chambers of Princes in the old Parliament building in Delhi once hosted the titular royals, often in full regalia. But, in 1937, a different gathering of uniformed men came to work in the room. The Government of India Act, 1935, had allowed a Federal Court—it stood above the Presidency High Courts of sweaty Bombay, Calcutta and Madras but below the Privy Council of cool and distant London.

But, already, the Privy Council had seen the erosion of the wide confidence it enjoyed among the Indian public. The turning point had come about a decade ago, because of a matter with the cause title of Bhagat Singh v King Emperor. A 19-year-old revolutionary had shot dead a 21-year-old British officer and surrendered his weapon. The much-publicised trial that followed created a legend. When Bhagat Singh’s appeal against his death penalty was dismissed by the Privy Council, the Empire’s injustices appeared in sharper relief.

‘We want our own men there,’ a restive population began to think. But they wouldn’t get them until 1947, when Harilal Kania was appointed the Chief Justice of the all-Indian Federal Court. In 1949, appeals to the Privy Council were abolished. The year after, in that very room in the Chamber of Princes, the Supreme Court of India sat for the first time. The highest court of the land was now officially of the land, for the land and in the land.

The Court has now spent three-quarters of a century working one of the world’s most extensive and ingenious constitutions. It has been a coveted task, but not an enviable one. “An independent Supreme Court,” Justice Kania had said in his inaugural address on 28 January 1950, “will have far-reaching influence on the constitutional history and progress of the Union of India.”

What has that progress looked like? Have the idealistic dreams and aspirations of 1950 come true? Over the years, there have been gleaming merits and damning demerits. Even the men—yes, mostly men—that variously ran the institution at different points will agree that it is still a work in progress. But, in this moment of commemoration, it is clear that the Court has gradually transmogrified into one of those uniquely Indian innovations that have earned our qualified admiration.

At the Supreme Court Observer, we analyse the institution’s proceedings—cases and judgments—to offer a day-to-day glimpse of its activities. But in this year of its 75th anniversary, we wanted to take a step back and widen the lens.

What, then, does it mean to be the Supreme Court of India? Beyond the building with the iconic dome (the move from the Princes’ Chamber happened only in 1958), the illustrious judges, the advocates that swarm and charm in the corridors, the billions that look up to it as the final dispenser of all that is just and true.

That’s the journey our special series hopes to capture, warts and all. Our founding editor Sudhir Krishnaswamy had the idea of looking at the court through the vantage points of some of the finer things in life—art, architecture, literature. That’s not to say we’re jettisoning our geeky, studied approach. So expect a lot of case law, verified back stories and intellectually rigorous assessments of the Court’s evolution and performance.

We will be publishing the special pieces throughout the year, so do watch out for them here. Our inaugural drop includes a study of the Court’s architecture (through which I learnt that the domed Court building is called a ‘rotunda’) and a crisp essay on legal dramas in Indian cinema.

Both these pieces have been curated by the writer and editor Snigdha Poonam, who is happily helping us with commissioning and shaping many more pieces to come. Hear from Snigdha in her own words below. And, after that, head to our website and read the stories. We hope that you will spread the word!

– Leena Gita Reghunath, Editor-in-Chief

***

To really know a country, an editor once told me, one must spend time in its courtrooms. It was a particularly valuable piece of advice in the Indian context, for it is in our courtrooms that we come the closest to finding out how well or badly the rights and freedoms promised to us as citizens hold up against the messy realities of an on-again, off-again democracy.

Yet, like most of India’s 1.4 billion people, I have a limited grasp of our judicial processes. That’s not due to lack of exposure. On the contrary, I have followed trials as part of writing stories about people who found themselves on either side of the judicial divide—perpetrators or victims —in cases that ranged from financial corruption to sectarian riots.

Each court visit added to my understanding, but I still couldn’t shrug off instinctive responses to judicial processes: impatient when the trials dragged on, disappointed when the verdict did not seem fair, and confused when the language sounded as if designed to elude comprehension.

When it comes to the Supreme Court, the stakes are even higher, for both our expectations and our outrage. We closely watch appointments, critique judgments, and lap up all gossip. Yet, we frequently fail to grasp why outcomes unfold as they do. So, when the Supreme Court Observer launched in 2018 with the mission to make daily proceedings at the court accessible to the wider public, I was impressed.

When they approached me to be a guest editor for the 75th anniversary series, I said yes immediately. The goal was to explore our justice systems through the lens of art and culture. Over the rest of the year, we will be publishing articles, essays, photographs, and cartoons that illustrate how culture shapes people’s relationship with the courts, and vice versa, in the world’s largest democracy.

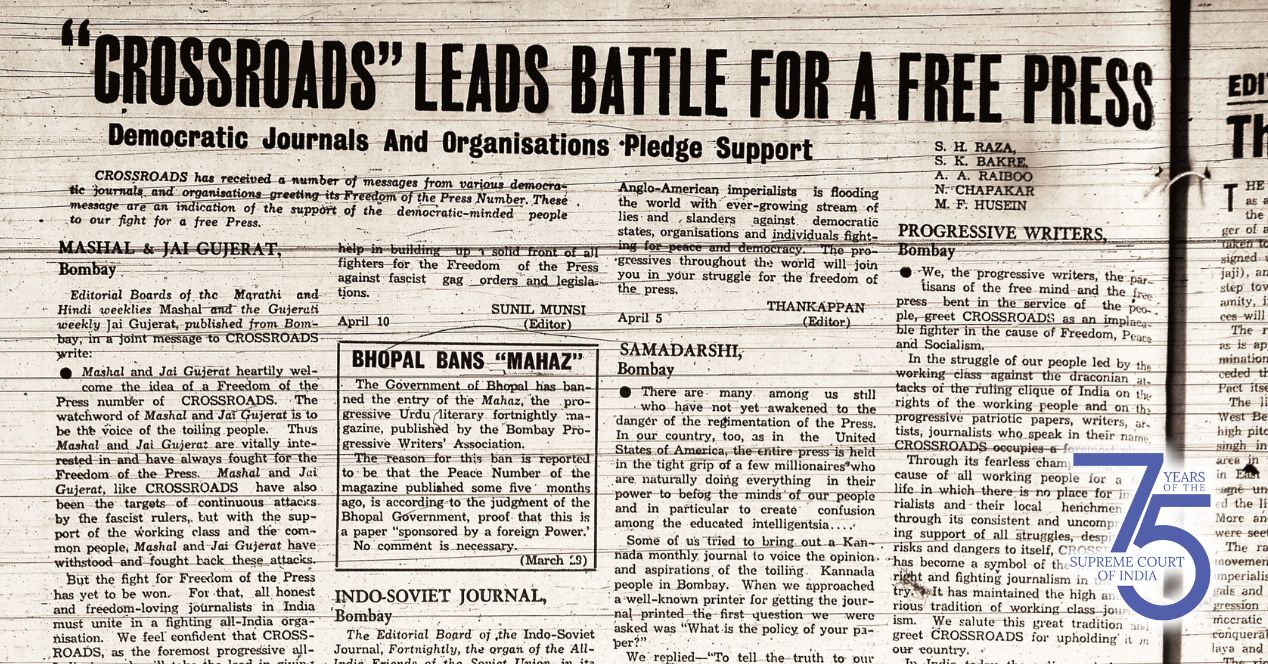

Going beyond what happens inside a courtroom, we will inquire why our courtrooms are designed the way they are and how their architecture influences their functioning. Why do popular actors in Indian films often portray lawyers but rarely judges? When was the first time an Indian court overturned a book ban?

Come for the answers, stay for the stories.