“Appealing to prurient interests”: Book bans, the courts, the mob

In an intolerant environment, decisions on book bans are increasingly being taken in bureaucratic offices, city streets and village squares

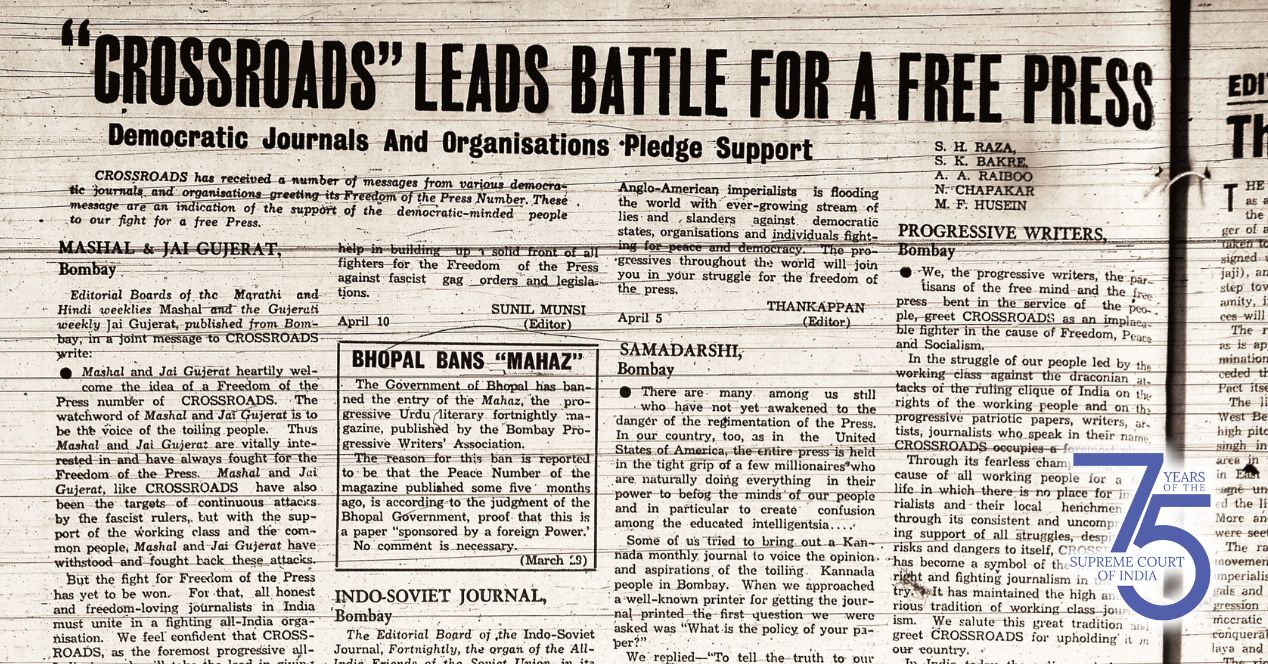

In 1954, a Baroda-based press published a book called Stree. It was Jayaben Thakore’s Gujarati translation of The Woman of Rome, a novel by Alberto Moravia. Set in Mussolini-era Fascist Italy, the story is about a woman who poses in the nude for artists and ends up becoming a sex worker. The novel was not obscene by any means, but its theme was considered risqué.

Morarji Desai, the puritanical Congress chief minister of Bombay state, banned the novel. The matter reached the courts, where intellectuals like the writer Chandravadan Mehta and the poet Umashankar Joshi defended the work.

D.J. Dave, the judge of the local court in Baroda, said that the mere depiction of a nude model, or the statue of an unclothed person, does not make a work vulgar. Dave ruled against the ban, noting that we have to embrace the times and not cling to values that are not in step with it. If we are to judge the worth of a literary work only by its impact on a sick mind, Dave said, we will be left with dull and meaningless works.

Chatterley and the “perversion of our literature”

Yet, within a decade, the Supreme Court went the other way in a landmark case. The centre of this storm was Lady Chatterley’s Lover, the 1928 novel by D.H. Lawrence. A bookseller named Ranjit Udeshi decided to challenge the administration’s ban of the book. In the early 1960s, after the Bombay High Court refused to overturn the ban, Udeshi took his fight to the Supreme Court.

It was the time when the Western world was turning away from such bans. The UK had lifted its ban on Chatterley—a fine critique of the hypocrisy of the British upper class—in 1960. But the Supreme Court ruled in favour of the government in Ranjit Udeshi v State of Maharashtra (1964). In a lively judgement revealing Justice Hidayatullah’s taste in modern literature and yet innate conservatism, we get a detailed account of evolving tastes in the western world, of moving from what cannot be said to what may be said. Hidayatullah relied on the Hicklin Test—whether a particular text is likely to ‘deprave and corrupt’ a prurient mind by immoral influences—to turn down Udeshi’s appeal and uphold the ban.

The Court’s reasoning was curious. It worried that overturning the ban on Chatterley would encourage writers in India’s regional languages to emulate the novel and “pervert our entire literature because obscenity pays and true art finds little popular support.” The Court didn’t engage with questions of literary merit or aesthetic, holding that “there [was] no social gain” from its distribution.

From personal experience, I can vouch that the judgement was difficult to enforce. In 1978, as a college student, I bought a pirated edition of Chatterley from a pavement hawker right across the road from the imposing edifice of the Bombay High Court.

Udeshi reflected a double standard that still recurs in the life of the republic—arbiters and decision-makers from the upper echelons of society taking on the role of protecting the ‘unwashed masses’ from baser instincts that could ignite their passions. It’s a straight line to this reasoning from the colonial idea of the ‘restless native’.

Judges in the higher judiciary are often erudite and well-read, with some even deploying elegant turns of phrase in their judgements to display their hidden literary persona. Within the confines of their tastefully appointed living rooms and chambers, they may read the risqué material and engage with provocative arguments. But this intellectual grappling is not for everyone, the Udeshi reasoning would have us believe; the vast swathe of society remains unprepared to deal with it.

Over the next few decades, the Supreme Court moved away from the Udeshi legacy, often siding with the author’s freedom of expression (though not in as emphatic terms as Dave, the Baroda judge). But, over those decades, publishers have increasingly shied away from the legal route when it comes to book bans. Instead of the courtroom, these battles are being fought on the street and in kangaroo courts, with authors, publishers and booksellers being arm-twisted by collective outrage. In these situations, the State has often stepped aside in the interest of maintaining the peace. The noise has been allowed to suppress the writing.

Bureaucratic censorship and court challenges

This is not a new development. Bureaucratic censorship has a long history in India, quite independent of what the courts have been saying. A few years before he banned Stree, the curmudgeon Morarji Desai ordered the arrest of the poet Majrooh Sultanpuri, who had written a verse critical of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Sultanpuri had referred to Nehru as “Hitler ka chela” (‘a stooge of Hitler’) and “Commonwealth ka das” (‘slave of the Commonwealth’).

In 1955, a year after Dave’s judgement on Stree, Indian censors banned the import of C. Aubrey Menen’s Rama Retold from the British publishers. The book, a satirical take on the Ramayana, was an early test of the limits of the secular republic.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, moral guardians went after a few Bengali novels on grounds of obscenity. In 1970, Buddhadeb Basu’s 1967 novel, Raat Bhore Brishti (It Rained All Night) was banned. An ailing Basu was kept in a cage during the obscenity trial, and copies of the novel were burned. Similarly, Samaresh Basu’s Bibar and Prajapati were banned, and it would take until 1986 for the Supreme Court to overturn the ban on Prajapati.

It may come as a surprise that India’s most widely reported and discussed book ban was never challenged in court. In 1988, the government prevented the import of Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses even while saying that that the ban “did not detract from the literary and artistic merit” of the work (A characteristically droll Rushdie thanked the finance ministry for its review of his writing). The writer Khushwant Singh, who was one of Penguin India’s consulting editors, had advised against publication.

In 1996, a Rushdie novel did reach the Delhi High Court. This was The Moor’s Last Sigh, whose import was suspended because the Shiv Sena was offended by a character that was obviously based on its leader Bal Thackeray. Rushdie named the character Fielding as a nod to Thackeray, both names of English writers, and had Fielding run a political outfit called Mumbai Axis, which lampooned the Shiv Sena. The High Court weighed in Rushdie’s favour.

City street and village square as deciding authority

The banning authority doesn’t have to undertake any legal gymnastics if it wants to go after a book. There are several provisions directly addressing the circumstance in the corpus of Indian law.

The criminal law includes provisions to prosecute those who have promoted enmity between groups or have outraged religious feelings. Section 95 of the Indian Code of Criminal Procedure (1973) (now Section 97 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita) specifically grants a state government the power to ban a book if it promotes enmity between groups.

Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code (1861) defines “obscenity” and criminalises the selling, distribution and possession of obscene material (This is now Section 294 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita. Section 294 has also included “display of any content in electronic form” within the ambit of obscenity.) There’s also Section 11 of the Customs Act (1962), under which imports of a book can be prohibited.

Limitations on authors’ freedom of expression are often justified on the grounds of ‘reasonable restrictions’ under Article 19(2) of the Constitution. The widely worded justification for these restrictions includes: the sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the state, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency or morality, contempt of court, defamation, and incitement of an offence.

In recent years, mobs have attempted to impose censorship by threatening to damage the bookshop or the work (such as burning books, or in the case of art, physically attacking the work), and in some instances, physically attacking the writer. Publishers have become cautious, for they have the duty to protect their own staff and property, besides safeguarding the freedom of expression of the writer.

The chilling effect is real—sometimes, publishers do not commission books on controversial topics, or do not accept such proposals. Manuscripts are scrutinised by lawyers to ensure that they don’t contain material that might fall foul of India’s laws and the sentiments of a community.

In 2013, the writer and critic Nilanjana Roy had observed that “in the last few years, the courts are no longer the main theatre where decisions about banning plays, film or art are carried out: instead, various groups, religious or political, have found direct action, vandalism or aggressive threats more effective.” The threats, especially those from fringe religious groups, cannot be taken lightly. In recent years, four rationalist and anti-caste writer-scholars have been murdered in India: Narendra Dabholkar, Dr M.M. Kalburgi, Govind Pansare, and Gauri Lankesh.

Community institutions outside the formal court structure also have an outsize influence on the fate of a work. The case of the Tamil writer Perumal Murugan serves as an illustration of those sensitivities. In 2010, the Tamil publisher Kalachuvadu published his novel Madhorubagan. The novel tells the story of Kali and Ponna, a childless couple. They cannot have children, so a plan is made for Ponna to be impregnated by a stranger at an Ardhanarishwara temple festival, where the rules of sexual conduct are relaxed for a night. The plot aroused the ire of the Gounder caste. Protests broke out in Tiruchengode. Copies of the book were burned, with calls to arrest the author and publisher.

At a community hearing that also saw the participation of officials from the district administration, Murugan was forced to apologise to the caste elders. He retreated into silence soon after, saying that he had committed ‘literary suicide’ and that the ‘the writer Perumal Murugan was now dead’.

But, in this rare instance, the mob didn’t have the last word. In 2016, the People’s Union for Civil Liberties filed a petition in the Madras High Court against the coerced settlement between Murugan and the caste elders. In response, criminal complaints were filed against Murugan.

Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul, then Chief Justice of the Madras High Court, ruled in favour of the author. “If you do not like a book, throw it away,” Kaul wrote, “All writings, unpalatable for one section of the society, cannot be labelled as obscene, vulgar, depraving, prurient, or immoral…The author and artists like him cannot be under a constant apprehension that if he deviates from the oft-treaded path, he will face adverse consequences…Let the author be resurrected to what he is best at. Write.” Murugan returned to writing after this affirming judgement.

While Kaul’s judgement was exemplary, it suggested that a work of high literary merit or aesthetic standards should have a different threshold than regular speech. While that might work in favour of writers and artists, it does not imply that satirists, dissidents and critics can take such a freedom for granted.

The thin-skinned State and information asymmetry

Murugan’s case brings me to another point—it’s easier to track cases that have been argued in the higher courts. Much of the detail about Murugan’s settlement with the caste elders wouldn’t have been on public record if PUCL hadn’t filed a petition in the Madras High Court.

There appears to be no comprehensive record or list of books banned in India. A crowdsourced compilation by the Software Freedom Law Centre lists 57 such books, but it is difficult to figure out who has sought the ban, if the ban is still operational, if it has been challenged or lifted. Information about ongoing matters in district courts is also not easy to come by.

The fact is that many state-level bans do not make the national news. In 2015, for instance, the Tamil Nadu government banned Senthil Mallar’s Vendharkulathin Iruppidam Ethu? (Which is the native of Ventharkulam?) and Kuzhanthai Rayappan’s Madurai Veeran Unmai Varalaaru (The True History of Madurai Veeran). “Both were provocative caste histories written by Dalits,” Kannan Sundaram told me, “We argued against the ban in our journal. The main point we raised is that caste Hindus write their history, implying that others are ruled by them. When such biased history is challenged by Dalit writers, it is seen as provocative.”

A look back makes it clear that parties across the political spectrum have instigated and lent their support to book bans. The bans involving Aubrey Menen, Ranjit Udeshi, and Salman Rushdie were initiated by Congress governments. The Communist government in West Bengal banned the works of Bangladeshi writer Taslima Nasreen, for fear of offending the Muslim community. Former Bharatiya Janata Party leader Jaswant Singh’s book on Mohammad Ali Jinnah was banned by his own party’s government in Gujarat in 2009. Two years later, the Gujarat government banned Joseph Lelyveld’s book on Mahatma Gandhi on the ground that it raised questions about Gandhi’s sexual orientation.

Governments and political parties have often been thin-skinned. In the years after independence, several Urdu works which dealt with Partition were unflinchingly considered incendiary. In 1962, Stanley Wolpert’s Nine Hours to Rama, a fictionalised account of Gandhi’s assassination, was banned, likely because it highlighted the security failures of the Congress government. During the Emergency, the Central Government banned Michael Edwardes’s biography of Jawaharlal Nehru, claiming that it contained factual inaccuracies.

Another matter that infuriates Indian bureaucrats is how India’s map is depicted in international publications, as if those drawings undermined India’s sovereignty. In Naravan Dass Indurakhya v State of Madhya Pradesh (1972), the Supreme Court overturned a Madhya Pradesh High Court judgement which upheld the state government’s ban on a geography textbook that carried a map with inaccurate borders.

Religions, coalitions, violations

Unsurprisingly, book bans are often justified on the grounds of protecting religious sentiments. Some of the early bans on religious grounds dealt with books on Islam. The Partition was also fresh in the memories of the administrators, jurists, and the public. Anything that might destabilise communal harmony needed to be scrutinised closely, and ideally, prevented from being published. The human cost, in terms of lives lost, exceeded the cost of silencing a writer—so went the thinking.

More recently, in a couple of cases around books that are critical of Islam, the Supreme Court demonstrated the distinction to be made between the genuine and malicious intention of the author. In R.V. Bhasin v State of Maharashtra (2010), the Court refused to overturn a ban on Bhasin’s Islam: A Concept of Political World Invasion. Previously, the Bombay High Court had upheld the ban on the ground that the author has “gone on to pass insulting comments on Islam, Muslim community with particular reference to Indian Muslims.” The bench referred to Bhasin’s work as “an aggravated form of criticism made with a malicious or deliberate intention to outrage the religious feelings of Muslims.”

In 2022, in Indian Muslim Shia Isna Ashari Jamaat v Union of India, the Supreme Court refused to entertain a Public Interest Litigation petition to ban Muhammad, a book written by Jitendra Tyagi. Tyagi was a former Chairman of the Shia Central Waqf board, Uttar Pradesh, and changed his name from Wasim Rizvi after conversion. The petition contended that Muhammad was “libellous, and incendiary in nature” and “extremely hurtful to the sentiments of the followers of Islam.” The Court dismissed the plea on the ground that Article 32 was not the appropriate remedy.

There is a perception that Hindus have been tolerant of criticism of their faith, and that the recent surge in Hindu groups’ opposition to certain books is a reaction to the success of Muslim groups in getting literary works banned. But that is not the case. The year before the Satanic Verses brouhaha, in 1987, the Shiv Sena had sought a ban on B.R. Ambedkar’s Riddles in Hinduism, which had been published by the Maharashtra government.

The Sena has also raised the cudgels about books that they consider as hurting nativist sentiments. In 2010, Mumbai University had to withdraw Rohinton Mistry’s Such a Long Journey from its syllabus after the Sena claimed that characters in the novel belittled the Sena and Marathi-speakers.

And, speaking of material on the university syllabus, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidhyarthi Parishad, the student-wing of the RSS, created a furore when it barged into the History department of Delhi University to demand the dropping of “Three Hundred Ramayanas”, an essay by poet and scholar A.K. Ramanujan, which detailed the multiple interpretations of the epic. In 2011, the Supreme Court directed the university to seek expert opinion and place the matter before the Academic Council. While a majority of Council members voted in favour of retaining the text, the Vice Chancellor decided otherwise.

The coalition years of the late 1990s and 2000s meant that many competing interests had to be balanced. In 2000, there was a temporary withholding of Sumit Sarkar and K.N. Panikkar’s Towards Freedom—the complaint was that it showed the Hindu Mahasabha in poor light. In 2004, Maratha activists ransacked the Bhandarkar Institute in Pune, after it emerged that the American academic James Laine had researched its archives for his book on Shivaji. Oxford University Press withdrew the book from circulation, but the Maharashtra government banned the book in any case.

After 2014, with the Bharatiya Janata Party in power in Delhi and in several states, both mainstream and fringe Hindu groups have been further emboldened to seek bans on books, films and television shows. In 2014, a Pune magistrate ordered the destruction of copies of two books on Marathi saints Dnyaneshwar and Tukaram.

The business of book bans

Besides obscenity, religion and politics, another powerful force that seeks book bans in India is business. In some instances, books published overseas have been allowed to be published in India, but with a missing chapter, as was the case with Siddhartha Deb’s The Beautiful and the Damned. The chapter was about Arindam Chaudhuri, who built a fortune in higher education. The chapter showed how Chaudhuri’s academic empire over-promised and under-delivered to its clientele. Deb was sued in a court in Silcar. The process became the punishment. In 2015, the Supreme Court transferred the case from the Silchar court to the Delhi High Court. Justice Madan B. Lokur, in the Supreme Court, described Chaudhuri’s lawsuit as “bogus litigation.”

In 2014, a stay order of the Calcutta High Court prevented the release of a book on the Sahara group by journalist Tamal Bandopadhyaya. The book was published only after a disclaimer authored by the Sahara Group was added to the book.

Jitendra Bhargava, who worked at Air India for more than two decades, was unable to publish his account of the airline after he was threatened with defamation suits.

In 1998, after the Reliance Group obtained an injunction from the Delhi High Court, Harper Collins India stopped the publication of The Polyester Prince, Australian journalist Hamish McDonald’s book on the rise of group founder Dhirubhai Ambani. The Reliance Group had told Harper that it would seek injunctions in all of India’s 22 High Courts if the book wasn’t pulped. Pirated copies of the book were available on the streets of Delhi and Mumbai in the 2000s (McDonald’s revised and updated works on the Ambani family are available in India.)

More recently, in 2018, yoga instructor and businessman Baba Ramdev was successful in obtaining an injunction from a trial court. The order restrained Juggernaut Books from publishing Priyanka Pathak-Narain’s book on Patanjali, Ramdev’s empire of ‘ayurvedic’ products. The case is waiting for its turn to be heard in the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court’s level-headedness

When it comes to book bans, the Supreme Court has shown itself to be sensitive to freedom of speech and expression. In some of the cases mentioned above—such as James Laine’s Shivaji book and Jaswant Singh’s Jinnah book—the Supreme Court has ruled in favour of authors and publishers. In 1977, it overruled Uttar Pradesh’s ban on Periyar E.V. Ramasamy’s Sachchi Ramayana in 1977.

Eighteen years after a case against him was first filed, the Supreme Court provided relief to Samaresh Basu, author of Prajapati. In Prajapati, the protagonist Sukhen leads a life that would be considered debauched by the standards of middle-class morality. In 1968, an advocate named Amal Mitra complained against the novel, on the ground that it would corrupt the morals of readers. In the trial court, expert witnesses refused to characterise the passages as obscene, and in fact praised the work’s forceful language. But the trial judge disagreed and convicted the writer and his publisher. The conviction was upheld by the Calcutta High Court, with the judge finding that the work was likely to “deprave and corrupt” the reader.

In the Supreme Court in 1986, Justices A.N. Sen and R.S. Pathak disagreed with the High Court, finding that kissing or sex need not be considered obscene. The bench also noted that what may seem “vulgar” need not be obscene. “If a reference to sex by itself in any novel is considered to be obscene and not fit to be read by adolescents,” the judgement says, “adolescents will not be in a position to read any novel and will have to read books which are purely religious.”

Onus on the executive

Ultimately, the Supreme Court can only answer the narrow legal question before it. It is therefore not enough to look to it for deliverance every time a book is banned. The banning of a book is an executive action, which comes with a loaded context. And the decision of the state may be influenced by other loaded contexts: the internet mob; hecklers at meetings and events; the real threats to the lives of writers and their publishers; the imperative to ensure maintenance of law and order.

The onus is on the executive more than the judiciary. Nobody is forced to read a book. If somebody does not like a book, they can stop reading it, tell others how bad it is, or even urge others not to read it. They don’t have the right to intimidate the writer to swallow their words or compel them to write about ‘safer’ topics. That infantilises a society.

It is the responsibility of the state to reassure the writer that they can work freely and to ensure that the publisher and bookseller feel safe. Instead, we have governments which encourage the hecklers and the offended, and ask writers to circumscribe their ambition and curb their imagination. During the Emergency, the Mumbai-based columnist Behram Contractor, who used the pseudonym Busybee, wryly noted that there were only two safe topics left to write about—mangoes and cricket. And, given the politicisation of cricket, perhaps now all we are left with are mangoes.

In such a scenario, the Supreme Court—and all courts—must continue to be the guardian of the right to express, to speak, to think. In some cases, the courts have risen to the occasion. In other cases, they have avoided responsibility, passing it back to the legislators. From a liberal society that should protect the speaker, India is turning into a society that protects those who claim offence at the slightest pretext. That’s why the courts must be readier than ever to protect the individual, the artist, from the wrath of the unimaginative collective.

Salil Tripathi is a writer based in New York. He was born in Mumbai, and is the author of four works of non-fiction. His latest book is The Gujaratis: A Portrait of the Community, to be published later this year. In 2009, he wrote Offence: The Hindu Case, about Hindu nationalism and attacks on free speech. He chaired PEN International’s Writers in Prison Committee and is now on its board.